My teacher Lama Yeshe Rinpoche once told me, in his characteristically blunt manner, “Some people have a lot of knowledge, a lot of wisdom. That’s not you! But you, you can actually do this practice. That is good.”

It is with those words still ringing in my ears that I approach this article. With so much brilliant contemporary scholarship on this subject from the likes of Glenn Mullin and B. Alan Wallace, among others, I have little to add insofar as academic reflection on Naropa’s instructions for using lucid dreaming for awakening. But what I can offer is an exploration of the essential core of this practice: What’s the point? How does it work? And how can we do it?

Tracing the Source

The notion that dreams have a role to play in the path of awakening has been a part of Buddhism from the beginning. In fact, the Buddha himself was attuned to the healing potential of mindful sleeping and lucid dreaming. In the Pali Vinaya, a kind of rulebook for monks and nuns, the Buddha instructs his followers to fall asleep in a state of mindfulness as a way to prevent “seeing a bad dream” or “waking unhappily.”

However, the first integrated Buddhist system of lucid dreaming—a form of mind training in which we become aware of the fact that we are dreaming while we are dreaming—was only created more than one thousand years later, amidst the flourishing of Vajrayana Buddhism, first in Northern India and then in Tibet. This system became known as dream yoga (milam naljor in Tibetan) and eventually formed part of the famous Six Dharmas of Naropa, a set of advanced tantric practices compiled by the Indian mahasiddha who is their namesake.

It would be easy to say that dream yoga is just a Tibetan Buddhist form of lucid dreaming, but that would be inaccurate. Dream yoga is a collection of trainings, including transformational lucid dreaming, conscious sleeping, and what we in the West refer to as out-of-body experience practices, aimed at bringing the practitioner to full spiritual enlightenment. Lucid dreaming may form the foundation of dream yoga, but through the use of advanced tantric energy work, visualizations of Tibetan iconography, and the integration of psycho-spiritual divine archetypes or yidams, dream yoga goes far beyond our Western notion of lucid dreaming.

To give an example of the complexity of Naropa’s teachings, in one dream yoga practice we 1) fall asleep imagining ourselves as a deity, while 2) simultaneously visualizing another deity in our throat chakra, while we 3) imagine our spiritual master or guru on the top of our head (or sometimes, quite poetically, that the pillow on which we rest our head is the guru’s lap).

This can be combined with 4) blocking both the ear and nostril of the right hand side as we 5) lie in the “posture of the sleeping lion” and 6) recite certain mantras and prayers for lucidity while also 7) drawing internal energy to one of the three upper chakras. I mention all of this to impress upon you the complexity and, to many Westerners, the exoticism of dream yoga practice. Unfortunately, I have often seen this complexity become burdensome for some practitioners, who can become so fixated on such complicated procedures that they struggle to get to sleep, let alone actually have a lucid dream.

The basic lineage of this particular branch of dream yoga practice is as follows: Naropa received the teachings from his teacher Tilopa, who received them from the Mahasiddha Lawapa, who is said to have received them from transmissions of the tantras as taught by the historical Buddha and revealed to him by Buddha Vajradhara. Other branches of dream yoga trace their roots to the eighth-century Indian master Padmasambhava and his bardo teachings, while many of the Dzogchen dream yoga lineages claim to stretch back more than three thousand years.

Whatever the case, we can confidently say that, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the discipline of dream yoga has been practiced for at least a thousand years, and as one of the famous Six Dharmas of Naropa, it forms an important element of the intensive three-year retreats that are central to this tradition.

It is believed that if we gain mastery over the mind of dreams through dream yoga, we will also have mastery over the mind of death.

In fact, in some lineages, dream yoga used to be practiced exclusively in the context of three-year retreat and was only taught as part of, and rarely separately from, the Six Dharmas of Naropa. These days, however, some of the veils of secrecy have been lifted, and dream yoga is adopted by growing numbers of dedicated practitioners to extend meditative awareness throughout sleep and dreams, and subsequently throughout the process of death and dying as well.

The Benefits

Dream yoga practice is often formalized into a series of stages—sometimes four, sometimes six, depending on the lineage—but for all of them, the first stage is always “recognition,” the act of becoming lucid. Once we have recognized that we are dreaming and become lucid, the dream state can become a potential workshop of enlightened action and spiritual growth in which mindful awareness, compassionate action, and the dissolution of negative mental tendencies can transform both our waking and dreaming experience, allowing us to see that there is ultimately no difference between the two.

There are so many benefits to be gained from becoming lucid listed in the teachings of Naropa, but let’s focus on just three of them now: preparation for death, recognition of emptiness, and spiritual practice while we sleep.

Lucid Dying

In the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, sleep is not just a metaphor for death, as it is in the West, but the prime training ground for death. Why? Because the after-death bardo state is said to be dreamlike in nature. It is believed that if we gain mastery over the mind of dreams through dream yoga, we will also have mastery over the mind of death. (It is worth noting that “sleep,” “death,” and “dreams” all have the same root syllables in Sanskrit.) If we can fall asleep consciously and recognize our dreams as dreams, we may also be able to die consciously and recognize the after-death bardo states.

According to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, if we can manage to recognize the dreamlike hallucinations of the forty-nine-day after-death bardo as manifestations of the mind, we have the possibility of experiencing full spiritual awakening. In his book Living, Dreaming, Dying, the late Buddhist teacher Rob Nairn wrote:

When we die, our stream of consciousness floats free from the body and roams the death bardos: the dreamlike hallucinatory experience that the mindstream enters into once it has separated from the physical body at the point of death. The mind is nine times stronger in this state and so if it is able to focus on spiritual truth it will immediately be drawn into it, experience it, and be liberated by it into awakening.

The teachings are clear—if practitioners can become fully lucid within the death and after-death bardo states, they have the potential to recognize the nature of their mind and reach full spiritual awakening. Dream yoga is the core training for this potential.

Lama Yeshe Rinpoche once told me, “If you want to know how your mind will be during death, look at how your mind is during a dream. If you can remember to recognize the dream consistently, then death means nothing to you, because you can recognize the death bardo as a dream, and then you can be with Buddha.”

Recognition of Emptiness

Shunyata, often translated as “emptiness,” is a Buddhist term used to describe the impermanent and interdependent nature of all phenomena. What it suggests is that reality is far from being the solid, permanent, objective truth that we believe it to be. It is more like a dreamlike illusion, empty of all inherent existence.

In the waking state, this concept can be hard to comprehend, but in a lucid dream we can experience first-hand that, however solid, real, and separate things may seem, they are actually a hallucinatory illusion created by our own dreaming mind. So, through lucid dreaming we directly experience a facet of emptiness. The brilliant scholar-practitioner B. Alan Wallace wrote in Dreaming Yourself Awake that “through dream yoga the yogi can directly recognize the emptiness of the personal self and of phenomena,” because if we can experience how convincingly real things are in our lucid dreams, we may become better able to experience the dreamlike nature of waking reality too.

Nocturnal Practice

Within Tibetan Buddhism, writes Michael Katz in Tibetan Dream Yoga, it is believed that “the mind is up to seven times more powerful” in the lucid dream state, meaning that any spiritual practice we do while lucid is charged with vast amounts of power.

In fact, doing spiritual practice in the lucid dream state is said to be so powerful that we have the potential to reach full enlightenment while we sleep. The first Karmapa, the initial spiritual head of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, attained full enlightenment at the age of fifty while practicing dream yoga. So, we shouldn’t think that spiritual practice in the lucid dream state is somehow second best to waking practice; it can actually be even more effective. In the dream yoga teachings of the great Namkai Norbu Rinpoche, it is said that “there may be extraordinary results from intentionally doing spiritual practice within a lucid dream” and that “one moment of spiritual practice in a lucid dream is equivalent to one week of spiritual practice in the waking state.”

Once lucid within a dream, to intentionally engage in meditation, prayer, deity visualization, or mantra recitation can be incredibly powerful, because our dream body is unhindered by the physical limitations of our waking body, meaning that we have the potential to reach levels of accomplishment that may seem impossible in the waking state.

Naropa’s teachings instruct us to visualize ourselves transforming into a buddha or deity once lucid in the dream. This kind of deity self-manifestation, in which we transform into the actual form of the Buddha and consequently experience that buddha’s luminous enlightened nature, is a very powerful experience.

Although many of these types of dream yoga practices (and especially the ones associated with the Six Dharmas of Naropa) require a qualified lama to teach them (and a student who has received the required initiations to receive them), there are some instructions that we can all practice, regardless of initiation. The Dalai Lama has said, “Dream yoga can be practiced by both Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike,” so let’s explore a practice, sourced from elements of Naropa’s teachings, that we can all do.

A Short Dream Yoga Practice

The dream yoga teachings tell us that our ability to recognize our dreams as dreams does not begin at bedtime, but during the day. Dream yoga is closely linked to, and sometimes even grouped together with, another of the Six Dharmas, illusory body yoga (gyulu). This is because the core of illusory body yoga—seeing all things as dreamlike and illusory—is, in and of itself, a way of inducing lucid dreams. How so? Because we often dream about our daily life. If we spend our whole day telling ourselves (and eventually actually seeing and believing) that all waking phenomena are like a dream, then at night we will dream about seeing everything as a dream and become spontaneously lucid. So, as you go about your daily life, try to see the dreamlike empty nature of all things and tell yourself, constantly, “This is all like a dream.”

The instruction above would be classified as a “daytime practice.” Now, let’s look at the “nighttime practice.” When taught as part of the Six Dharmas of Naropa, the achievement of lucid dreams is often said to be dependent upon the fruition of tummo, the yoga of inner heat, but those who cannot do this may also achieve lucid dreaming by the “force of conscious resolution.” There are two main steps to doing this.

First, before bed, we recite a prayer to have lucid dreams. The following one is to be said three times out loud to one’s guru or to Buddha: “Tonight may I have many clear, lucid dreams and may I recognize my dreams for the benefit of all beings.”

Then, as we are falling back asleep after a brief intentional awakening just before dawn (feel free to use an alarm clock), we affirm, over and over again, our strong intention to have a lucid dream by reciting in our minds to our guru or to Buddha as we drift off to sleep, “May I recognize my dreams as dreams,” at least twenty-one times. This prayer, recited as we fall asleep, can be repeated every time we fall asleep, but is said to be most effective any time after dawn, as the body has been restored by sleep and the mind is more clear.

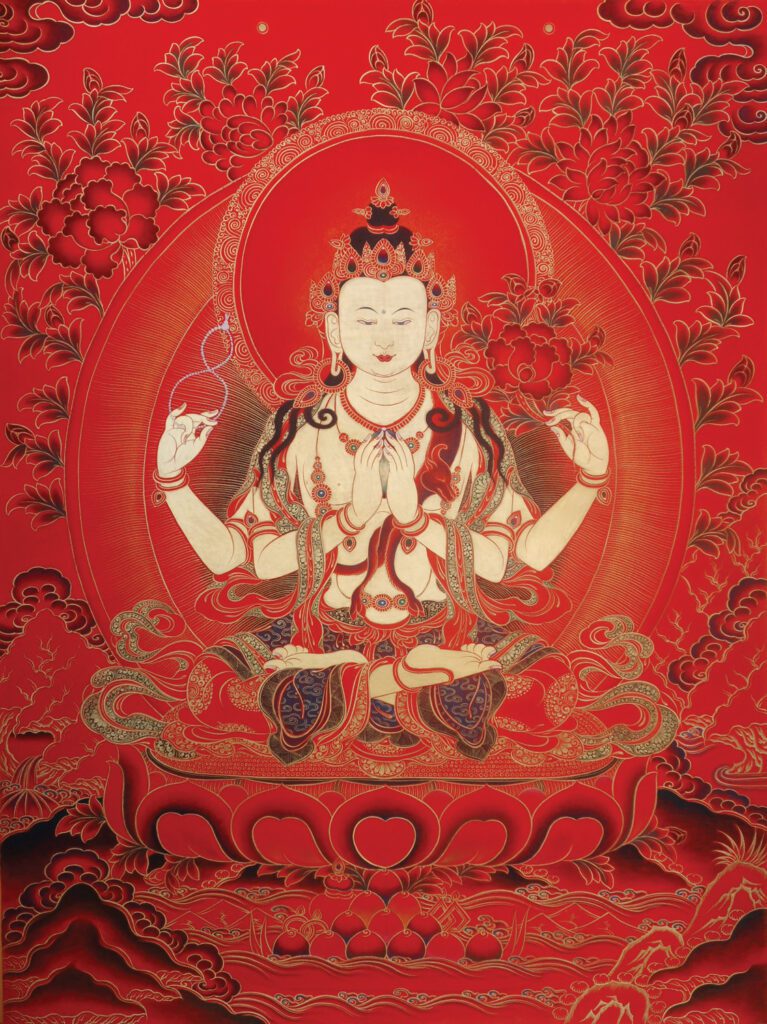

Then, if we have become lucid, the teachings instruct us to intentionally do a series of practices, such as transforming fear (as a way to free up stagnant energy), doing impossible things (as a way to see the pure potentiality of the dream), and eventually, engaging in deity self-manifestation. This final stage is usually restricted to Vajrayana initiates, but the teachings tell us that, as Nairn wrote, “people who can dream lucidly but have not been initiated can visualize the embodiment of compassion, Chenrezig, and recite the associated mantra in their lucid dreams.”

Chenrezig (Sanskrit: Avalokitesvara) is the buddha of infinite compassion. As with each specific deity in Vajrayana Buddhism, there is a mantra associated with Chenrezig, and it’s well-known: Om Mani Padme Hung (Sanskrit) or Om Mani Peme Hung (Tibetan).

Just saying Om Mani Peme Hung once in a lucid dream is said to be one of the most beneficial things you could ever do and will plant such a powerful seed of infinite love that your life and all future lives will be beneficially affected by it.

Once you become lucid in a dream, recite the mantra out loud, over and over again. Then, if possible, visualize Chenrezig in the space in front of you. Use a painting of Chenrezig (e.g. page 52) to familiarize yourself with the image. Don’t worry if you can’t visualize the image very clearly. If the image is too difficult to summon, you may instead choose to visualize a ball of compassionate white light. But make sure you say the mantra. That’s where the real power is.