My body’s illness is congenital. It combines an irritation of the nervous system, degeneration of the skeletal system, and the gradual disappearance of all connective tissue in the body. Now, ten surgeries later, both hips, shoulders, and one knee are artificial. I’ve also had surgery for cancer. I take fentanyl and tramadol to help with the pain. And I practice dharma.

The illness first manifested in 1960, during puberty when I was a sophomore in high school. The doctors ordered bed rest for six months to try to prevent severe curvature of my spine. I had to lie on a board with a round pillow under my neck and use special prism glasses for reading.

While I was lying there, I read a Jack Kerouac novel and decided to study Zen. I read every book by D.T. Suzuki I could get my hands on and Paul Reps’ Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. Lying on my back, I tried to do zazen. After about a month, something began to manifest; either a profound mystical experience or an enduring makyo, the perceptual distortions or hallucinations that can occur during zazen.

Whether he was a makyo or something else, an Asian man appeared to teach me how to do zazen correctly. He worked with me every night for two months. He taught me to sit in a full lotus position and to practice lying down. He was abrasive. His eyes were fierce. He was dressed in a red robe, and he stomped around the room holding a long staff topped with a brass trident. He gave me koans to ponder. He was terrible and he was wonderful. When he seemed satisfied with my practice he disappeared, never to return. I may never know what this experience was, but I practice today because his teaching was exactly what I needed.

At that time, the pain was primarily in my lumbar vertebrae. It made sitting zazen painful. In fact, sitting still was almost impossible for any length of time. Later, when I tried to explain this illness to coordinators at Rinzai or Soto centers, I was told not to try a sesshin if I couldn’t sit still. I asked if I couldn’t sit someplace in the back, where I would not disturb anyone. I was told no. (This was during the sixties and early seventies.)

On a scale of one to ten, the pain was pretty much at a six or seven all of the time.

After a while, I gave up trying to find a community and practiced alone or with friends. In the mid-eighties, I thought I’d try again and approached the Providence Zen Center for permission to do a retreat. I was given an interview with Seung Sahn, its Korean Zen master. On the day of the interview, I was nervous and scared. Directed to his room, I knocked three times before an angry voice finally yelled for me to come in.

Soen Sa Nim (as his students called him) had a serious flu. His face was red, his nose was dripping mucus, and he was coughing violently. Aghast, I just stared at him. I was completely at a loss as to what to do.

He gave me a cursory look and said, “Get me some Kleenex!”

I handed him a box. He blew his nose and handed me the used Kleenex. I threw it away.

He said, “What do you want?”

I said, “I want you to be my teacher.” “Humph!” he said. “Who are you? What’s your story?”

I told him a little about myself, my illness, my practice, my reading.

He stared at me for a while.

Then, “You shouldn’t come here to practice. This place is getting ready to come apart. Write me. We will do some kong-an [koan] practice in the mail. Don’t write long letters. Just use postcards. Your first kong-an is ‘Does your dog have buddhanature?’ ”

He angrily blew his nose again and waved me out.

As I was leaving I asked, “So, will you be my teacher?” I felt confused and uncertain about what had just happened.

“Yes, yes,” he replied, as if I were stupid.

We wrote for three years before he passed me on kong-an practice and told me to stop writing him. In the short notes he wrote me, he was brilliant and profoundly compassionate.

By this time I had been practicing for twenty-five years, with almost no sense of community. My pain was also becoming generalized, in every joint system of my body. On a scale of one to ten, the pain was pretty much at a six or seven all of the time. I spoke to some close friends and made a decision to commit suicide.

A friend suggested I try vipassana and gave me the name of Joseph Goldstein, who lived nearby in western Massachusetts, at the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre. I visited him and felt an immediate connection. When we first sat together in his apartment, I had an experience of deep samadhi. I formally asked Joseph to be my teacher and the following month I took refuge and received the precepts in a Pali ceremony he led under a tree at IMS.

I began to work intensively with Joseph. He started me on Buddhaghosa’s Visudhimagga. It was Joseph’s belief that deep jhana practice would enable me to stop experiencing pain as the central reality of my identity. He was right. Vipassana and jhana meditations saved my life.

I attended a two-week immersion course in the dharma at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies (the scholastic campus of IMS), where I experienced sangha for the first time and made dharma friendships that endure to this day.

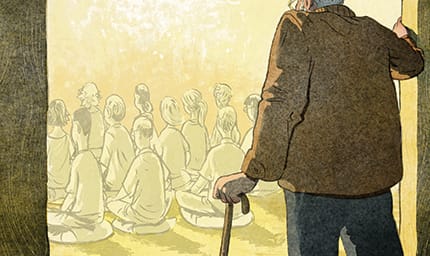

The two-week intensive culminated in a threeday sit. This was my first experience in years of sitting with “strangers.” It was agony. I watched my body twitch with pain. My joints became so aggravated by the sitting that walking meditation became a limping travesty of movement. I went to a dharma interview with one of the retreat leaders and found myself sobbing. He encouraged me to use the jhana states as a refuge when the pain became too intense. That got me through the retreat, but it seemed a temporary fix to me.

The following year I signed up for a ten-day retreat with Joseph, Guy Armstrong, and Sharon Salzberg. By the second day of the retreat, the pain levels were up around eight. I was not sleeping at night. During the formal meditations, I sometimes passed out because of the lack of sleep. I had to stop doing the walking meditation. I was perspiring with the intensity of the pain. I noticed people moving away from my chair, which was in the back of the meditation hall to avoid attracting attention. One person even broke silence to tell me I was a drag and shouldn’t do a retreat if I couldn’t do it right!

During the time I was in this personal hell, Joseph asked me to speak with a young paraplegic man. He was carried in and out of the retreat hall and placed on a pillow for the meditations. He used a wheelchair to get around IMS. Talking with him raised all the issues I was experiencing as well. Despite our conversations, he continued to go deeper into depression and finally felt he had to leave the retreat early. Though he said he got comfort from speaking to me and expressed gratitude, I felt profoundly useless in addressing his suffering and my own.

Finally, after eight days of no sleep, I crashed and had to call a friend to come get me. I was numb from exhaustion, depressed, and my medication was barely touching my pain levels. This sense of failure made me go deeper in my practice when I returned home. I was determined to find a relationship to my body that was friendly, compassionate, and skillful.

I remember one night when pain levels were at a ten. My perceptual field was breaking up. My senses were not working coherently. I called Joseph, almost hysterical. I could not meditate at all. Joseph stayed on the phone with me for an hour, returning me to my breath over and over again—gently, patiently, compassionately, until I was able to stay with it. My clinched attention loosened up. The knot around my ego’s identification with the body let go, and the witness reappeared. Subjective suffering disappeared. The pain was no longer all-powerful. I felt human again.

This is the possibility that the dharma offers me. I can remain compassionately human in the midst of profound affliction—even in constant pain or with a disability that almost separated me from the world. Dharma practice does, in fact, explore the very basis of all awareness, and points to a reality beyond alienation—a reality where I am interdependently linked to all living creatures.

After two years under Joseph’s guidance, I found a place that allowed me to live at peace with the physical pain. Joseph suggested that I meet his core teacher, Anagarika Munindra, who talked with me about my practice. He and Joseph gave me permission to start teaching. I wanted to work with people like me—people who did not fit into ordinary practice, who were alienated, outside, disabled, or chronically ill. Obviously, given my own limitations, my teaching is limited to a small number of individuals and special venues.

Recently I began teaching a meditation class at the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland for people with disabilities, illnesses, or other conditions that make it difficult to sit with others. The class is called, appropriately, “Every Body, Every Mind.” After fifty years of seeking, I have finally found my dharma home.

A Sangha for Every Body

Jim Willems knows what it’s like to feel unwelcome at programs because of his disabilities. He offers the following advice to help sanghas initiate a dialogue between those who are healthy and ablebodied and those who are not.

To the person who is differently embodied:

- Know your limitations. Find out what you can and cannot do with respect to sangha, such as sitting with other people.

- Speak directly and honestly about your condition with members of your sangha. if you can’t do this, you are in the wrong place or you need to do more personal work.

- Insist on the right to participate but remain compassionate and respectful of the impact your presence may have on others. Your presence during a meditation session may not always be skillful. accept this reality.

- Find a teacher or dharma friend who can stand with you and support you. You will need a dharma companion whose wisdom can help you in your practice.

Recommendations for the sangha:

- Be honest and direct about your response to the differently embodied person. For example, if the person is constantly having tremors or spasms that make it difficult for you to practice, say so. remain present to and responsible for the impact you have on the differently embodied person.

- Create a space that allows the differently embodied person to practice. Be imaginative in thinking about the possibility of a sangha that includes all people.

- recognize that people are different and so are their experiences. Do not use the clichéd responses, “We are all one” or “Your oppression is an illusion” to dismiss the other’s experience. You may have little sense of what it is like to be a differently embodied person. Many people have been mistreated or not included precisely because of who they are. Deal with it.

- When possible, make sure your teachers are representative of diverse communities, including people with disabilities.