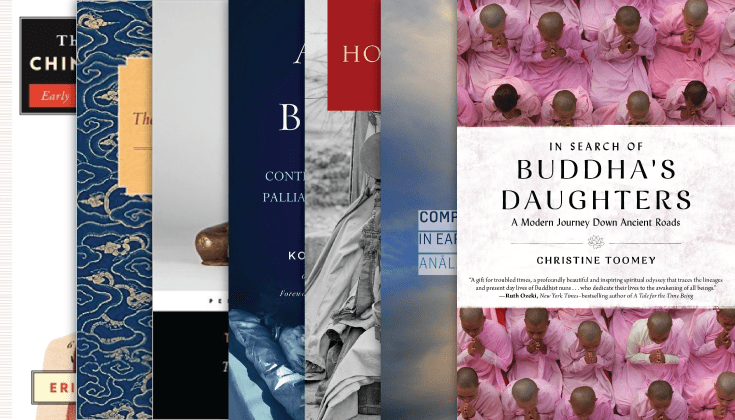

David M. DiValerio’s The Holy Madmen of Tibet (Oxford 2015) examines some of Tibetan history’s most fascinating figures. Diving straight into the grotesque for which these fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Kagyu “madmen” became known, DiValerio begins by describing Tsangnyon Heruka’s use of human remains as clothing and Drukpa Kunle’s verse about paying homage “not to the Buddha, but to an old man’s impotent member.” While the stories about these teachers are shocking (and highly entertaining), DiValerio frames their actions as a kind of “tantric fundamentalism” that involved taking Buddhist tantric texts literally and emulating the transgressive behaviors they detail. Far from being unhinged, DiValerio suggests they were upholding a vision of tantric Buddhist orthodoxy in order to forge a new identity for the Kagyu order—one that would provide a clear alternative to the conservative monasticism of the surging Gelug school.

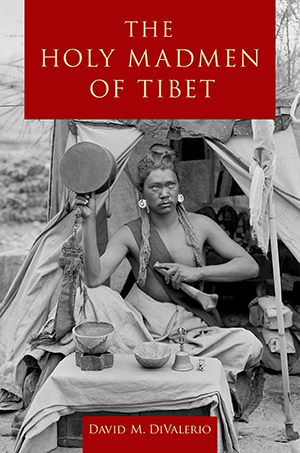

Awake at the Bedside (Wisdom 2016), edited by Koshin Paley Ellison and Matt Weingast, is the most helpful book on palliative and end-of-life care I’ve read. Ellison, a Zen Buddhist priest and cofounder of the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care, and Weingast, the director of communications at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, carefully combine some of the best writing available about death and care for the dying. This includes medical doctors discussing the problematic ways in which the dying are treated in modern hospitals and strategies for getting around these shortcomings. It also includes advice from dharma teachers, beautiful poetry, and personal stories that can help us face experiences of illness and loss.

Boudhanath (aka Boudha), Nepal, has been a Buddhist pilgrimage site for centuries, and old photos show a once quiet hub that would soon be home to thousands of Tibetan refugees. With the Tibetans came new monasteries and a growing community of Western Buddhists looking to study under Tibetan teachers. Echoes: The Boudhanath Teachings (Shambhala 2016) documents Thinley Norbu Rinpoche’s conversations with a group of Westerners, Tibetans, and Bhutanese during his visit to Boudha in 1977. Their exchanges are fascinating, addressing topics ranging from the state of Buddhism in the West to the Buddhist prerequisite for killing insects to the potential uselessness of meditation retreats. Having lived in Boudha myself, reading this made me feel nostalgic (though the Boudha I know is very different from that of the late 1970s), perhaps because it so perfectly captures the enthusiasm and curiosity still found among Boudha’s diverse Buddhist communities today.

There are many versions of the Buddha’s life story, each with its own embellishments, twists, additions, and subtractions. In The Life of the Buddha (Penguin 2015), written by the eighteenth-century Bhutanese author Tenzin Chogyel and introduced and translated by Kurtis Schaeffer, we find one of the most accessible versions available, free of excess detail and scholastic detours. As Schaeffer observes in his introduction, Tenzin Chogyel’s retelling also has remarkable emotional depth, as seen in the Buddha’s last conversation with his son Rahula: Rahula approaches his father sobbing, and the dying Buddha comforts him by saying they have been good to each other as father and son and that in nirvana they will be free from suffering. But he also acknowledges they will never share such a relationship again, adding a poignant and human touch to a transcendent scene.

Christine Toomey’s In Search of Buddha’s Daughters (The Experiment 2016) takes us on a worldwide trek to meet some of Buddhism’s most dedicated women. Relating a two-year, 60,000-mile journey, Toomey recalls her encounters with women such as the famous nun/singer Ani Choying Drolma, whose early experiences of abuse prompted her to seek refuge in a nunnery high in the hills of the Kathmandu Valley. In Burma, Toomey finds a mother–daughter duo running a strict and highly respected Theravadin nunnery in a nation witnessing a massive boom in ordained women. Heading west, Toomey then interviews American nuns such as Thubten Chodron, who argues that her abbey—which admits women and men—reflects the different sort of experience available to Buddhist nuns in Western countries, being “more collaborative, with gender equality and with seniority based on years of experience and knowledge.” Seamlessly narrated, this book reveals the varied paths available to women seeking to dedicate their lives to Buddhist practice.

In Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation (Windhorse 2015), prolific Theravadin monk–scholar Analayo focuses on works from the Pali Canon and parallel passages in other languages, revealing how these two ideas that are so often linked with the Mahayana are in fact important for numerous Buddhist traditions and their practices, including Theravada. What stands out about this book is that although Analayo focuses on ancient texts, he consistently addresses the needs of contemporary practitioners, making it a welcome addition to any serious meditator’s library.

Erik J. Hammerstrom’s The Science of Chinese Buddhism (Columbia 2015) examines early twentieth-century Chinese Buddhist responses to science. This book is not an assessment of Buddhism’s compatibility or incompatibility with science but rather a careful look at how Buddhists in China tried to reconcile their traditions—including belief in supernormal abilities—with empiricism. By offering glimpses into how Chinese Buddhist intellectuals faced the authority of science, Hammerstrom gives us much to think about as we watch leading Western Buddhists pursuing comparable projects today.