Tantra, also allied with Vajrayana Buddhism, refers to the yogic traditions of esoteric practice that arose in Northern India around the middle of the first millennium CE, as well as to the scriptures of those traditions. It arose outside of the established religious institutions of the day but was later pursued by both monastic and yogic practitioners. There are both Buddhist and Hindu tantric traditions.

Tantric teachings and practices are designed to accelerate one’s spiritual progress and lead to enlightenment. Tantra builds on the insights and habits developed in mindfulness and awareness meditation practice. Contrary to some modern interpretations, Buddhist tantra is not primarily about sexual practices. The tantric tradition strongly emphasizes the need for practicing under the close guidance of an advanced teacher or teachers.

Tantric Path and Methods

Tantra is sometimes used synonymously with the general term Vajrayana (adamantine or diamond-like vehicle), which refers to one of the vehicles or paths within what is known as the three-yana system.

The first yana, the Foundational Vehicle, emphasizes mindfulness and awareness practice, good conduct, and the development of insight. The second vehicle, the Mahayana (great vehicle or wide path), emphasizes the bodhisattva path of working for the benefit of others. The Foundational Vehicle and the Mahayana are sometimes known as causal vehicles because they teach the causes of imprisonment and freedom and, in this way, show the paths to liberation.

Tantra, or Vajrayana, the third yana, is known as the fruitional vehicle because it is based on the radical insight that enlightenment—the result of the path—is already within us to be revealed rather than something to be produced by effort. The name tantra comes from the Sanskrit term for the threads on a loom, which was later translated into Tibetan as gyu or continuity. This “continuity” refers to the fact that the ground of our confused samsaric experience and the realized state of buddhahood are one and the same and remain unchanged. This unchanging nature is simply obscured, and the tantric path removes the obscurations.

Tantra is also known as the path of method (Sanskrit., upaya), because whatever experiences and situations arise in our life can be used as methods for realizing enlightenment. The rituals, mantras, mandalas, feasts and visualizations of tantric practice are methods for connecting practitioners to the fundamental nature of their ordinary experience.

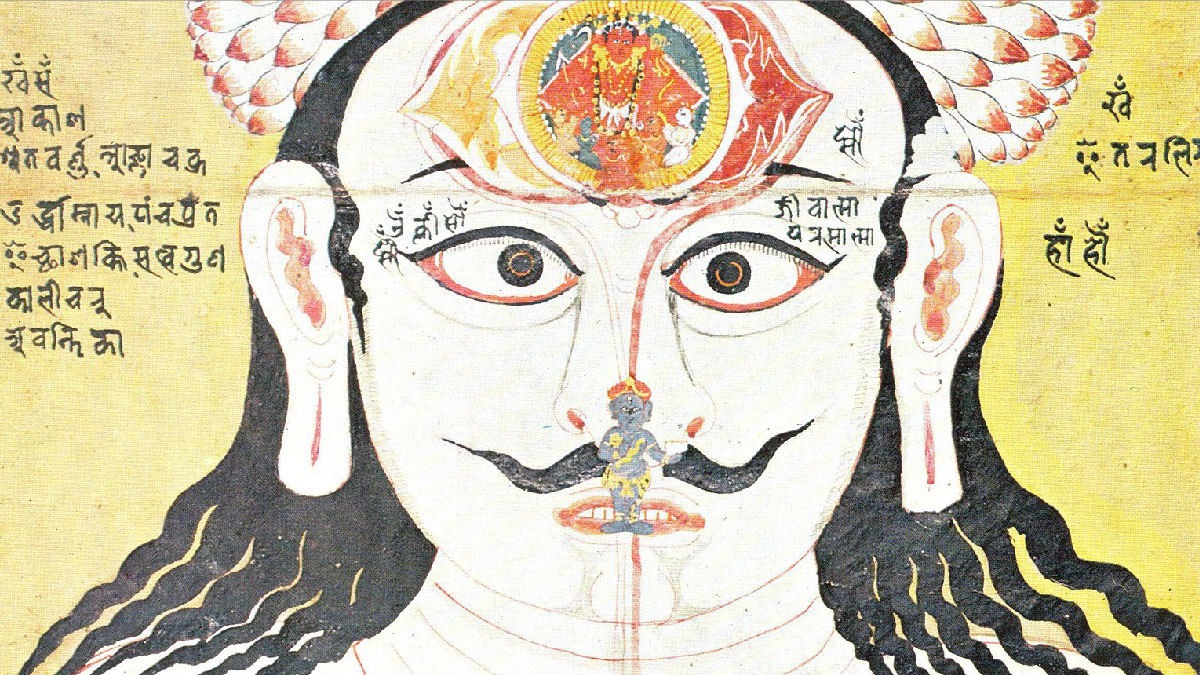

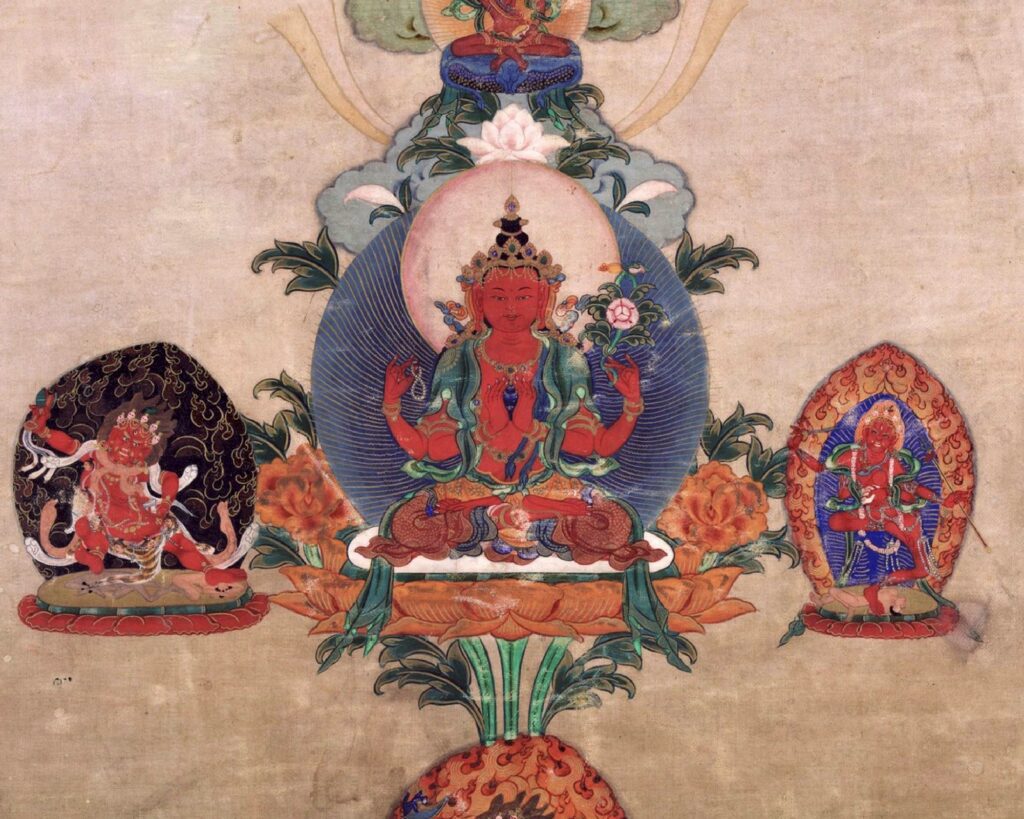

There are two main tantric approaches to meditation practice. The “path of method” includes a generation stage, in which practitioners visualize various mandalas and deities, and a completion stage in which all the visualized phenomena dissolve into emptiness, resulting in formless meditation—meditation without any object of meditation.

The “path of liberation” includes shamatha, in which practitioners rest with whatever appears in their minds, and vipashyana, in which they look directly at these phenomena in order to recognize their empty, luminous nature. Two major traditions of this kind of practice exist: Dzogchen and Mahamudra. The goal and realization of each of these are fundamentally the same; the differences lie in the methods and emphasis.

Tantric Lineages and Teachers

The tantric teachings are primarily passed down through the four main lineages of Tibetan Buddhism. While practitioners of all of these four share teachings and practices with each other, each lineage is particularly associated with certain kinds of practices.

The oldest of the four main schools, the Nyingma, is especially associated with Dzogchen teachings and the great teacher Padmasambhava. Prominent modern-day teachers within this lineage include Dilgo Khyentze Rinpoche (1910-1991), author of Primordial Purity et al; Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (1920-1996), author of Rainbow Painting, et al; Thinley Norbu (1931-2011), author of White Sail, et al; and Rabjam Rinpoche (1966-present), author of The Great Medicine That Conquers Clinging to the Notion of Reality.

The Gelugpa lineage was founded in the late fourteenth century by the teacher and scholar Je Tsongkhapa, who promoted the importance of analytical meditation to establish the correct view of emptiness. Prominent contemporary teachers include His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama (1935-present), author of The Art of Happiness, et al; and Thubten Yeshe Rinpoche (1935-1984) and Thubten Zopa Rinpoche (1946-2023), co-founders of Kopan Monastery in Nepal and the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition.

The Kagyu Lineage is known for preserving the Mahamudra teachings, and its most well-known historical figure is the singing yogi Milarepa. Prominent modern-day teachers include Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987), author of Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism et al.; Thrangu Rinpoche (1933-2023), author of Essentials of Mahamudra et al.; and the head of the lineage, His Holiness, the Gyalwa Karmapa, among many others.

The Sakya lineage is renowned for its scholarship. Prominent teachers include the great nineteenth-century guru Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, who was one of the prime movers of the Rime movement, which promoted non-sectarianism in Tantric Buddhism. The most prominent current teacher is the head of the lineage, Sakya Trichen (1945-present), author of Freeing the Heart and the Mind.

Relationship to General Buddhist Teachings

While they are esoteric, tantric teachings are nevertheless directly connected with both the foundational meditative teachings of the Buddha and the bodhisattva ideal of compassion of the Mahayana tradition. Tantric practices are understood simply as methods and contemplations that can accelerate the realization that is the goal of all forms of Buddhism.

Related Reading

The Power of Buddhist Tantra

Gaylon Ferguson on how tantric view and practice help us turn confusion into clarity and wisdom.

Vajrayana Explained

The late Karma Kagyu master Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche presents a clear explanation of the view of Vajrayana and its main practices of generation and completion.

Zen Mind, Vajra Mind

The late Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche described Suzuki Roshi as his “accidental father” in America, and through their close friendship he gained great respect for the Zen tradition. In this talk, Chögyam Trungpa looks at the basic differences between Zen and tantra.

Buddhism A–Z

Explore essential Buddhist terms, concepts, and traditions.