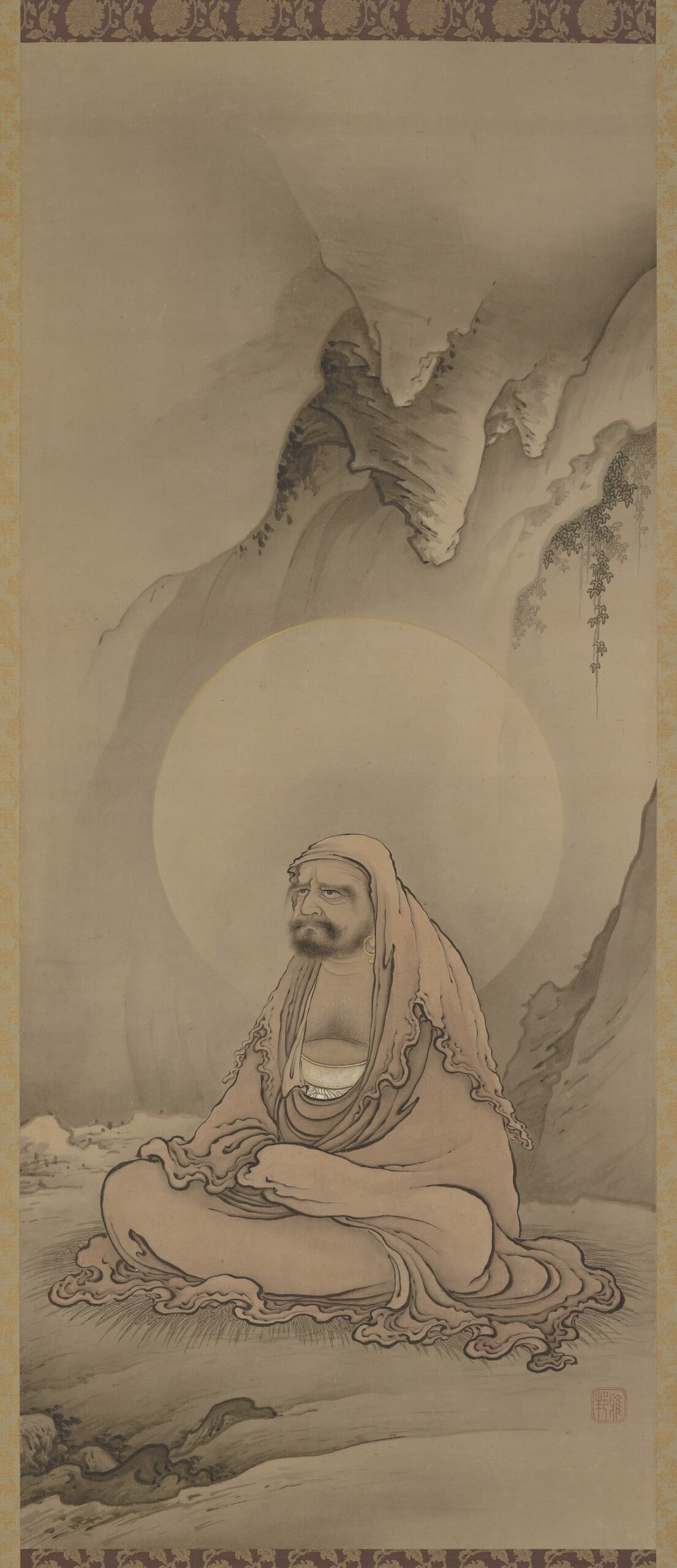

If you want to understand the full truth of “form is emptiness; emptiness is form,” says Robert Aitken Roshi, you must go beyond the Heart Sutra to philosophical texts like the Huayan Sutra, which unpack and elaborate this profound paradox.

I once attended a memorial service for an old grandmother in Mishima, Japan. She had been a Zen student, and members of her family had connections with Shingon and Nichiren sects as well. A priest from each of these three denominations took part in the service, and they joined in reciting the Heart Sutra together.

The Heart Sutra says that form is emptiness; emptiness is form; form is exactly emptiness; emptiness exactly form. Moreover, sensation, perception, formulation, and consciousness are also like this. This seems to be an unnatural kind of contradictory intelligence, but it is the expression that is contradictory—there is no contradiction in nature. Very strange things live side by side in evident harmony—intimate harmony, even identity. The Heart Sutra is an exposition of nature, essential nature, the way things are.

Only 276 words, the Heart Sutra is a very brief text, abbreviated from a monumental work, the Prajnaparamita Sutra, probably the Astasahasrika edition of 8,000 lines, which was composed just before the Common Era. The Heart Sutra was produced shortly thereafter. And that evening in Mishima, it was recited together by priests of disparate sects, and it is recited every day in almost all Mahayana temples in Japan, China, Korea, and Vietnam, except those of the Pure Land, and has been recited there every day for 1,600 years and more. Today you will hear it daily throughout the Buddhist diaspora beyond East Asia.

Furthermore, in East Asia, it is not translated. It is recited, and has been recited, in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam using the original Chinese ideographs. Once, I took my teacher Nakagawa Soen Roshi to visit a Chinese Buddhist temple in Honolulu. The resident priest was very hospitable, and showed his Japanese guest the sutra book used by his sangha. The roshi turned to the Heart Sutra, and he and his Chinese host recited it together, syllable by syllable, each using his own, slightly different pronunciation. They didn’t miss a beat and ended precisely on the same note.

Contrary to some scholarship, the fullness of the Heart Sutra’s import does not lie in the original sutra’s 8,000 lines, but rather in the way the boiled-down message is treated philosophically in the multivolume Huayan Sutra and in other Mahayana sutras, and experientially in the thousands of cases or koans offered for study in Zen Buddhism.

About the Huayan, or Flower Ornament Sutra: it is translated in full by Thomas Cleary, with useful introductory material and guides through the elaborate text. I am most grateful to Dr. Cleary for his cogent labor of love. Koans, too, have been translated by Cleary, Yamada Koun Roshi, and others. Now it is time to bring the Huayan, koan study, and the Heart Sutra together in a single presentation.

The heart of the ecumenical recitation of the Heart Sutra, there in Honolulu so long ago, lies in the timeless lines:

All things are essentially empty –

not born, not destroyed;

not stained, not pure;

without loss, without gain.

The profound implications of this grandfather of complementarities (form is emptiness, emptiness form) are explored by Donald Lopez in his comprehensive, scholarly work The Heart Sutra Explained, and here and there by others in a scattering of studies. “Complementarity” is still not a familiar term, though it has a venerable usage. It was resurrected by Nils Bohr, the Danish physicist, more than a hundred years ago, when he sought to show how the two theories of light, wave and particle, which seem to conflict with each other, are not only both true, but taken together they present a meaning that neither can offer alone. The logical ambiguity is itself a clear presentation of the phenomenon.

Everybody knows about the world of form. We see it all around us every day, and in and as ourselves as well. Few really know about emptiness – that is to say, really blank nothingness. Some would-be teachers actually deny it, the way others deny dukkha, leaving Buddhism hanging in midair, without a ground floor or a basement.

Here is a conversation we had at our center at Kaimu on the Big Island of Hawaii a few years ago:

Question: I guess I don’t understand how form can be empty.

Response: I don’t either, but you don’t grasp it with the cortex. It is more a matter of the large intestine. You know, science tells us that the particles, the essential particles of this lectern, are as far apart from each other as the Earth is from the nearest star, in relation to their size. I imagine that when you examine those essential particles, you find they are not essential at all, but are made up of even more basic particles that are further from each other than the earth is from the nearest star, in relation to their size.

Question: Boy, you’ve lost me [laughter].

Response: Yes, I’ve lost your cortex, and I apologize. But your large intestine is serene, I dare say. I am reminded of the story Gary Snyder tells about the Native American shaman explaining how a turtle supports our continent, and another turtle supports the first turtle, with supportive turtles, one below the other, all the way down.

Question: Not really empty.

Response: Exactly. I have an idea that the two theories of light can be explored ad infinitum too. It took a Nils Bohr to cut through the limitations of the cortex and present the natural fact. It takes the Zen student to do the same thing. A simple experience like rolling over in bed can show that everything is empty, totally empty, with not a particle to be seen anywhere, if one is prepared for the experience and can handle it when it comes.

Question: How does one handle it?

Response: By remembering to floss.

Question: Isn’t that form?

Response: Indeed it is.

Right you are. “Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em, and little fleas have lesser fleas, and so on ad infinitum.” It may be “turtles all the way down,” but they don’t stop being turtles. The Zen experience is altogether different.

There are two ways to understand emptiness: First, it is true for phenomena. As we discussed in that question-and-answer session, the particles that make up a thing are as far apart from each other as the earth is from the nearest star, in relation to their size. And whereas it is possible to weigh those particles, it is also possible to show that they have no weight. What are you left with? Zilch, nada, mystery.

The second way to understand emptiness is to realize that words and concepts, including all the rich categories of Buddhism from the three jewels to the three poisons, have a purely provisional status and a purely utilitarian value. There is no existing entity to which they correspond.1 That takes care of Buddhism, one might suppose, not to mention all other religions and moral philosophies.

But not so fast. Emptiness is form. The beauty of the Mahayana lies in the experience it offers of grandfather complementarity: A is not true, at least not fundamentally. Likewise B. Now AB – that’s a different story, a different foundation.

It is AB that every master seeks to clarify, and every writer on Zen worth his or her salt seeks to clarify. The 8,000 lines of the Prajnaparamita Sutra were set forth succinctly in the Heart Sutra, and commentaries by the great Fazang and a few others clarified the multivolume Huayan Sutra.2 The cases studied in Zen offer the clarification of both sutras in succinct wording that is conducive to realization experience.

A monk asked Zhaozhou in all earnestness, “Does a dog have buddhanature, or not?”

Zhaozhou said, “Mu.”

Or at least that’s the way we say it, using the Japanese of our old teachers, which is probably close to the Tang-period pronunciation used by Zhaozhou.

Mu means “does not have,” but, as I assured a certain new student, that wasn’t Zhaozhou’s point entirely. Time after time, the student came to me for consultation. I would ask, “What is mu?” He would just stare back at me and say nothing. It might have seemed that he was not progressing, but I learned better from his girlfriend. “I am worried about him,” she said, “He is always weeping.” Heartened by this good news, I continued to wait. And wait, and wait.

I don’t have permission to tell the rest of the story. Suffice it to say that it has a happy ending that is still playing itself out. It is the prototype story of countless workhorses of the past. The complementarity of form and emptiness is meaningful only when it is fully resolved in the small and large intestines. Thus it behooves the master to take excruciating care. I knew a teacher who said about a new successor, “I gave him a break. I think in time he’ll grow into it.” There are successors of that successor now, a bunch of gutless wonders, I have to say.

The Huayan Sutra

Like the complementarity of form and emptiness of the Heart Sutra, and similar complementarities in koan study, with the truth clearly set forth in seeming ambiguity, the Huayan Sutra is charged with logical absurdities. Time is immediate and infinite, godlike beings walk around as teachers of you and me, and wheels turn within wheels.

The old masters were intimately familiar with the Huayan and occasionally referred to it, but their remarks and the sutra were as different as a joke is from its exposition. Yet, I suppose, there is not a single case taken up for Zen study that could not somehow be explicated by using the remarkably elaborate figures of the Huayan, particularly from book 3, the Gandhavyuha, an extended folk story that relates the pilgrimage of the youth Sudh-ana from beginner to realized master as a template for the pilgrimage of all students who seek full and complete realization.

The saga of book 3 begins with the youth Sudh-ana who has resolved the complementarity of form and emptiness, and like others who have taken that important step, he is ready for true practice. He meets Manjushri, the incarnation of wisdom, who sets him on his way. The youth encounters a succession of fifty-three masters–laymen and ordained, male and female, human and spirit. Ready for complete maturity, at last he meets Maitreya, the future buddha, the potential of us all. Maitreya leads him to his tower and has him enter. As the door shuts firmly behind him, Sudhana surveys the interior:

He saw the tower immensely vast and wide, hundreds of thousands of leagues wide, as measureless as the sky, as vast as all of space, adorned with countless attributes; countless canopies, banners, pennants, jewels, garlands of pearls and gems, moons and half moons, multicolored streamers, jewel nets, gold nets, strings of jewels, jewels on golden threads, sweetly ringing bells and nets of chimes, flowers showering, celestial garlands and streamers, censers giving off fragrant fumes, showers of gold dust, networks of upper chambers, round windows, arches, turrets, mirrors, jewel figurines of women, jewel chips, pillars, clouds of precious cloths, jewel trees, jewel railings, jeweled pathways … Also, inside the great tower he saw hundreds of thousands of other towers similarly arrayed; he saw those towers as infinitely vast as space, evenly arrayed in all directions, yet those towers were not mixed up with one another, being each mutually distinct, while appearing reflected in each and every object of all the other towers.3

For all this marvelous attainment, there is still another step to go. Sudhana goes on to his final teacher, Samantabhadra, the incarnation of universal good. This is the bodhisattva of great action, saving the many beings as final fulfillment of our first vow. With all the complex wealth of the tower of Maitreya, Sudahna is prompted to full and complete enlightenment. Great! Wonderful!

However, the old masters bought Sudhana down to Earth and the mud of the farm. Here is Sudhana’s transformation and expansion in the tower, and here is his utterly profound realization with Samantabhadra:

Xuefeng asked a monk, “How old is this water buffalo?”

The monk did not respond. He answered himself, “Seventy-seven.”

The monk asked, “Why should you, Master, become a water buffalo?”

Xuefeng said, “What’s wrong with that?”4

Indeed. Another example of Huayan wisdom that is then applied in Zen would begin with Fazang’s demonstration of the Hall of Mirrors arranged for the Empress Wu Zetian:

Your Majesty, this is a demonstration of totality in the dharmadhatu. In each and every mirror within this room you will find the reflections of all the other mirrors with the Buddha’s image in them. And in each and every reflection of any mirror you will find all the reflections of all the other mirrors, together with the specific Buddha image in each, without omission or misplacement. The principle of interpenetration and containment is clearly shown by this demonstration.5

Right here we see an example of one in all and all in one—the mystery of realm embracing realm ad infinitum is thus revealed. The principle of the simultaneous arising of different realms is so obvious here that no explanation is necessary. These infinite reflections of different realms now simultaneously arise without the slightest effort; they just naturally do so in a perfectly harmonious way.

The early master Changsha absorbed the Hall of Mirrors in the most intimate and personal manner. Fazang and his elaborate visual aid disappear:

The entire universe is in your eye; the entire universe is your complete body; the entire universe is your own luminance; the entire universe is within your own luminance. In the entire universe there is no one who is not your own self.6

For the mature Zen student, this hits the nail on the head. Whammo! The abrupt rise of realization from one’s innards is the understanding at last of Walt Whitman’s cry, “I am large; I contain multitudes!” My eye contains multitudes. But what unmerciful fun the old boys would have made of Whitman!

Xuesha said, “I hear that Changsha said, ‘The whole universe is in your eye.’ Well, if that’s so, where will you fellows go to defecate?”7

Indeed. What do you say, old Changsha? He didn’t have to say anything. Zhaozhou put it all in perspective: “Where will we go? Well, if you are on your way to see Xuefeng, take along this mattock.”8 Zhaozhou and Xuefeng knew very well what Changsha was talking about, and were simply offering tests to their students in his spirit. Well done! What do you say?

1 Francis H. Cook, Hua-yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977), p. 40.

2 Ibid., pp. 32 - 33, 48, 59.

3 Thomas Cleary, The Flower Ornament Scripture, Vol. 3 (Shambhala Publications, 1987), pp.365 - 366.

4 Nelson Foster and Jack Shoemaker, The Roaring Stream: A New Zen Reader (Ecco Press, 1976), p. 129.

5 Garma C. C. Chang, The Buddhist Teaching of Totality (Pennsylvania State University Press), p. 24.

6 Isshu Miura and Ruth Fuller Sasaki, Zen Dust: The History of the Koan and Koan Study in Rinzai (Lin-chi) Zen (Harcourt Brace & World, 1966), p. 275.

7 Thomas Cleary and J.C. Cleary, The Blue Cliff Record (Shambhala Publications, 1977), p. 31.

8 Mattock, an earth-turning tool used by early farmers, East and West. Not a trowel or a hoe, as some translators would have it. Cf. James Green, The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu (Shambhala Publications, 1998), p. 141.