This weekend many people in the U.S. will celebrate Juneteeth National Independence Day (Juneteeth). Given that this will be the first full year that this federal holiday has been in effect, it is unlikely many people in the U.S. will really know about it. This lack of knowing may be eerily similar to the fact that the formerly enslaved people freed by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 didn’t know it until 1865. Even with the use of social media, it still takes time for information to be recognized as fact, metabolized in one’s psyche, made meaning of in one’s heart, and actualized in one’s behavior. Yet, Buddhist and Zen practitioners say Buddhists and Zen practitioners are always about the business of liberation. I see evidence of that sentiment because we are very small in number in the U.S., but much larger in cultural impact. How can that be?

Juneteeth can be an opportunity for anyone to reflect on everyone in the long lineage of U.S. freedom-holders.

Historians of Buddhism in the U.S. are well positioned to answer the question of our cultural impact, but I know from my lived experience that meditation, mindfulness, compassion, and service continue to run through this country, even in the midst of our death-dealing present situation. I know that Dr. Katsugoro Haida, Shunryu Suzuki, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Pema Chodron, the Insight Meditation Society founders, Thich Nhat Hanh, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Lion’s Roar, Shambhala Publications, Wisdom Publications, Beat Poets, International Buddhist Film Foundation and BuddhaFest, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Rev. angel Kyodo williams, and many more people and cultural artifacts (statues, jewelry, monasteries, books, fine arts, etc.) have contributed to the cultural impact Buddhist and Zen practitioners have made. But what cultural icons represent Juneteeth? Who was the first enslaved person who recognized as fact, metabolized, made meaning, and actualized in their behavior that Black folks were free?

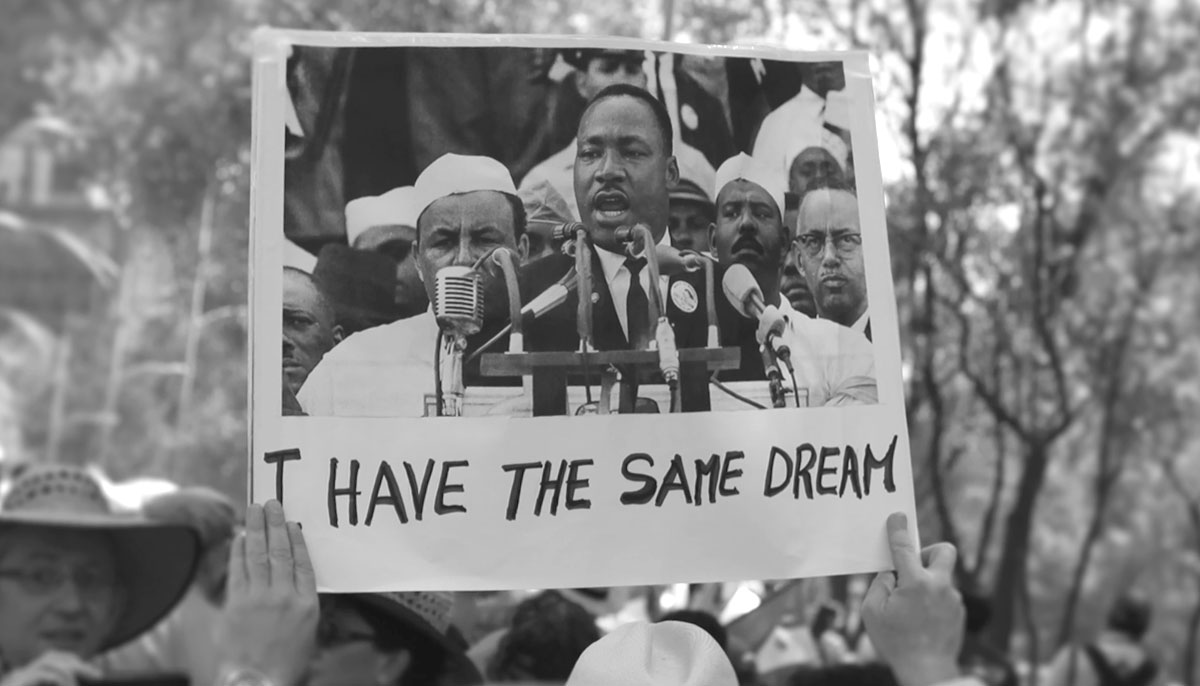

Until we produce more Juneteeth cultural artifacts, I suggest, just for this weekend, we take another look at Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but through the eyes of African American Buddhist practitioners Jan Willis, Thomas Davis IV, and Larry Ward. Let’s bring Black Baptist and Black dharma reflections on King and his legacy outside the cultural conditioning of limiting our appreciation for him to an annual federal holiday in his name. Juneteeth can be an opportunity for anyone to reflect on everyone in the long lineage of U.S. freedom-holders of which King belongs. Maybe you belong there too. Happy Juneteeth!

—Pamela Ayo Yetunde, Associate Editor, Lion’s Roar

Black, Baptist, and Buddhist

By Jan Willis

I had been raised in the Baptist Church and it was in that religious context that I first observed, and learned, non-violent, activist values. Indeed, my first real practice of these values came through participating in the Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign (the Campaign).

In 1963, as a fifteen-year-old tenth grader, I marched with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Campaign. Accepting rides downtown from our county school bus drivers, I marched as often as I could during those weeks of protests. How sad and ironic then that now–some six decades later–we Black people (though today with more allies) have had to resort to mass marches once again. The ’63 Campaign led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the famed “Bloody Sunday” Selma March led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Yet, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted most of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act is an archival text more than a document that guarantees Black, Brown, and poor people actual civil rights. Martin Luther King, Jr. would have turned 93 years old this January. I wonder what he would make of our current social, political, and spiritual situation.

Both King and the Buddha extolled the cardinal virtue of working for the benefit of others.

Marching with King in Birmingham taught me several important moral lessons: the importance of non-violence, the importance of love and forgiveness, the importance of discipline, and of courage even when afraid. Dogs scared me, the Birmingham Fire Department’s water cannons drenched and pelted me and scores of other young marchers. But we showed up, marched, sang, and were arrested. We were buoyed by the conviction and certitude that our struggle was just and right, and that we would therefore, ultimately, triumph. And we did experience some victories. (Still, as Carol Anderson’s White Rage has amply illustrated, for every step forward by the people, there has been backlash.)

When I later encountered the teachings of the Buddha, I discovered many of the same principles and teachings I had gleaned from the Civil Rights Campaign. Indeed, finding so many of the same spiritual values espoused by both Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Buddha was, for me, like coming home. The Buddha taught, in Dhammapada verse 183:

Do no harm, Practice virtue, Discipline the mind. These are the teachings of all the Buddhas.

King had studied the teachings of both Mahatma Gandhi and those of the Buddha on the moral rightness of non-violence as well as their stances on resisting unjust and oppressive powers.

King had seen the interconnectedness and interrelatedness of reality, saying,

All men (sic) are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.

For Buddhism, whether termed, pratitya-samutpada (dependent-arising), or sunyata (the emptiness of permanent, inherent existence), the fact of interconnectedness is a cardinal principle.

And both King and the Buddha extolled the cardinal virtue of working for the benefit of others. In Buddhism, this action is often referred to as being a bodhisattva, “one who seeks always to help others.” King famously said: “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’” Often, in Buddhist texts, the bodhisattva is referred to as being “brave.” When King spoke of the “Good Samaritan” in one of his famed sermons, he said not only that “The Samaritan was good because he made concern for others the first law of his life,” but that the good Samaritan practiced “a dangerous altruism.”

So, what are we to think, and to do, now as we move into another year racked by the continuation of the Covid pandemic, by ultra-partisan political divides, and by rampant racial animosities, injustices, and inequities? I think we must do what these two great religious leaders have shown us: We must continue to love one another, and, out of this love, we must commit to act, non-violently, for the true benefit of all.

Reclaiming the Essence of Order and Meaning

By Thomas Davis IV

Music has been central to all of my life experiences; particularly the genres of Soul, Hip-Hop, Gospel and ultimately, Jazz. These vibrational elements continually address the spiritual dimensions of my life by continually forging, shaping and deepening my heart and mind while opening me to further contemplative explorations! I learned to love Gospel music in the Baptist Church because I often found myself within the lyrics of the songs that were sung. Melodically powerful stories of my struggle, my hope and my ultimate triumph over opposing circumstances. These devotional elements were essential to helping me find a sense of order and meaning on both personal and shared collective levels, which created a deep sense of connection within the community. Although I’ve practiced within Buddhist communities for the past 10 years, I have found no equivalent to the power of devotion offered through the Black Baptist Church.

Creating one’s own sense of order and meaning is an ethical responsibility.

Upon my early entry into the Buddhist community it was nice to know that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, and his philosophy of non-violence were highly-revered by Buddhists, and this initially provided me with some reassurance that I, a Baptist Minister, would also be received well. Because of my Black Baptist experience, I also seemed to have a deeper understanding of how Dr. King made it through some of his darkest days of the Civil Rights struggle and a good deal of that support came through was the essential musical elements of the Black Baptist community. My continued study of Dr. King led me to see that he, like me, held a deep appreciation for other musical genres besides Gospel. I will share some of his perspectives on Jazz music and the historic role that it has played in the creation of order and meaning on racial,social, and economic magnitudes.

In 1964 at the Berlin Jazz Festival, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. submitted an essay to be shared with the jazz community. He did not orate his thoughts out loud, but wrote them in an essay. it is said that his words “loomed large,” during the three-day festival. I will share a brief excerpt from his essay for reflection.

Dr. King said, “Jazz speaks for life. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.”

Dr. King observed that the underlying intention of jazz musicians is to create “order and meaning” for themselves when life fails to offer it. This method of creating order and meaning requires an attunement and receptivity to the sounds, vibrations and resonant frequencies of the Earth itself. This caused me to reflect upon jazz artists and their impact on my life over the years. Particularly, the jazz artists who created order and meaning in the ambiguous realms of Avant-Garde Jazz.

Creating one’s own sense of order and meaning is an ethical responsibility. Buddhist philosophy espouses the virtues of ethical conduct, truthfulness and strong determination as essential qualities to cultivate, inform and sustain one’s direct experience.

From my Black, Baptist and Buddhist American perspectives, my living experiences have been perpetually signified by the lack of order and meaning on racial, social and economic magnitudes. My accomplishments and aspirations on the secular and the spiritual paths offer no protection from the fact that life sometimes does not offer order and meaning. Nonetheless, the transient absence of order and meaning furnishes me with the determination and passion required for a consistent exploration of life.

To be clear, one does not have to appreciate jazz in order to notice a void of order and meaning in your life experience. However, we can explore the possibilities of creating order and meaning through the examples that jazz artists have set.

The question is…”Can you feel and hear the sounds of the Earth? Have you discovered your authentic expression of order and meaning? How can our devotional and spiritual practices support our creation of order and meaning that is socially relevant?

I have an innate proclivity to innovate, which ties directly to my African American Ancestral lineage. The evasive nature of order and meaning within historic Black communities framed the conditions for the creation of Gospel, Blues, Jazz, Rock and Hip-Hop. There has always been a need to create dimensions of order and meaning within Black Communities.

I hope that Dr. King’s perspectives inspire your own orderly and meaningful creations!

Speaking Truth to Minds, Hearts, and Systems

By Larry Ward

The following excerpt illuminates the profound nature of Dr. King’s understanding of how a deep transformation is required in America’s attitudes, values, habits, and systems: “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.” In this speech, Dr. King called for the United States to “undergo a radical revolution of values,” saying that “we must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society.”

He continued: “When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.” Certainly, this posture called into question the American status quo’s tolerance, maintenance, and protection of a system of oppression based on colonial models of thought, speech, and action both individual and collective.

A Bodhisattva’s spiritual practice invites them to face and embrace their fears.

To speak such truth to minds, hearts, and systems of power reveals Dr. King’s embodiment of the Bodhisattva’s deep practice of nonfear. This means the Bodhisattva learns continuously to face their fears and not be debilitated by them. In the words of Judith Lief, “Fear is not a trivial matter. In many ways, it restricts our lives; it imprisons us. Fear is also a tool of oppression.

Because of fear, we do many harmful things, individually and collectively, and people who are hungry for power over others know that and exploit it. We can be made to do things out of fear. Fear has two extremes. At one extreme, we freeze. We are petrified, literally, like a rock. At the other extreme, we panic. How do we find the path through those extremes?”

A Bodhisattva’s spiritual practice invites them to face and embrace their fears, understand their fears, and release them through wisdom and compassion in action. Dr. King describes the impact of fear in our lives: “The soft-minded man always fears change. He feels security in the status quo, and he has an almost morbid fear of the new. For him, the greatest pain is the pain of a new idea.”

Dr. King’s life called me in and out of hiding into my own unique voice. I found myself full of openness to the creation of a new future for America, and deeper still called into the Bodhisattva path of universal care. So, I call you in and out as Dr. King did me and as we must do for one another. In his words, “And so there are things that all of us can do and I urge you to do it with zeal and with vigor.”

I conclude this brief description of Dr. King as a Bodhisattva with a quote from TNH. It is a beautiful expression of the Bodhisattva’s vow: “We have enough suffering already, so we don’t want to make any more. We have enough suffering for us to give rise to awakening. We want to avoid making more suffering, if we can. We want to use the suffering that’s already here to help us to wake up, to awaken.” And will we wake, for compassion’s sake?

Excerpted from essay “They Call You a Bodhisattva: Homage to Martin Luther King Jr.” by Larry Ward, PhD, anthologized in Afrikan Wisdom: New Voices Talk Black Liberation, Buddhism, and Beyond edited by Valerie Mason-John (Vimalasara), published by North Atlantic Books, copyright ©2021 by Valerie Mason-John (Vimalasara). Reprinted by permission of publisher.