John Malkin talks to Sister Chan Khong about peace, war, emptiness and working with Thich Nhat Hanh.

Born in 1938 to a well-respected family on the Mekong River Delta, Sister Chan Khong learned at a young age the importance of caring for the sick, the hungry and the powerless. Her grandfather told her, “We have no money to leave you, but we bequeath you the merit we have earned from helping people in need.” She first went to help the poor at age 18.

In 1964 Khong, then a twenty-six-year-old biology teacher, helped Thich Nhat Hanh establish an organization to bring medical facilities, school supplies and other essential equipment to war-ravaged rural Vietnam. A few years later she traveled with him to Paris as part of the Buddhist Peace Delegation, trying to influence the peace talks aimed at ending the Vietnam War. Their desire for sanity and peace in the world led to the founding of Plum Village, a retreat center in France. Their sangha now includes major centers in California and Vermont.

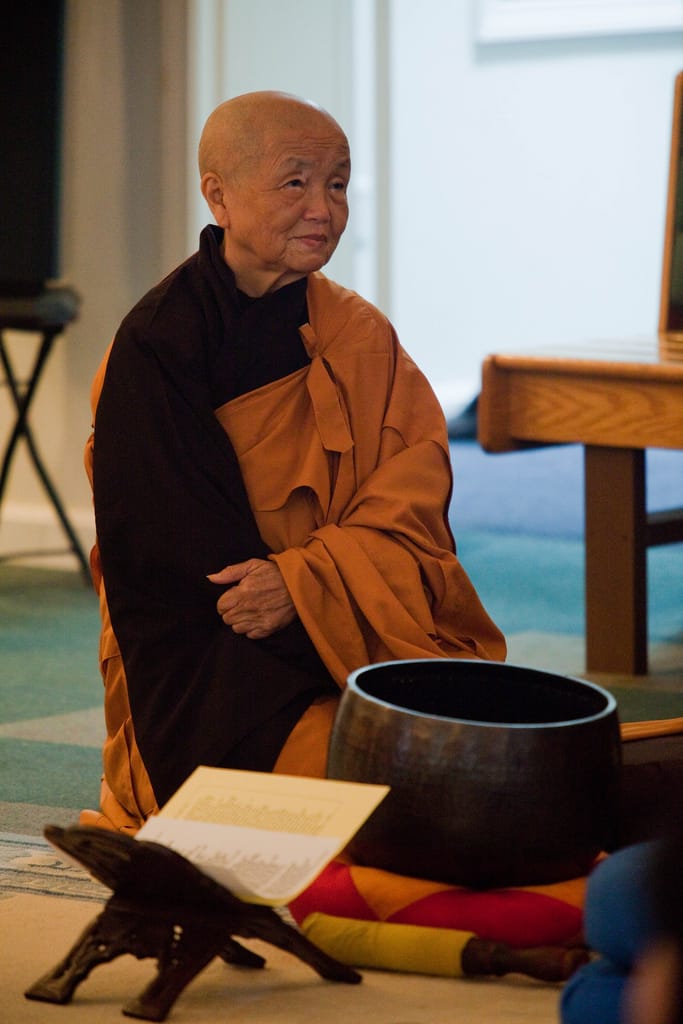

Sister Chan Khong and Thich Nhat Hanh have been working together for more than forty years. She is the driving force behind many of the organization’s efforts. She raises funds, talks publicly about their work, makes important community announcements and works out the details for countless projects. She also protects and cares for Thich Nhat Hanh, whom their community calls Thay (the Vietnamese word for teacher, pronounced “tie”). She is the gatekeeper helping decide with whom Thay spends his time.

Sister Chan Khong is known in Plum Village and beyond for being jolly, loving and quick to laugh, despite her many responsibilities to an ever-growing worldwide sangha.

John Malkin: Can you tell us about some of the experiences in Vietnam that inspired you to work for social change?

Sister Chan Kong: I grew up in the city, which was then a safe area. The war was going on in the countryside and it seemed very far away. In Saigon, people were going out dancing and eating delicious food at fancy restaurants. At a certain point, I revolted against that. I refused to go to fancy restaurants with my family. I knew there was something to do and I was determined to get involved. I read in the newspaper about one of the big battles, where a lot of people had died. Many people would read the paper in those days and soon forget what they had read, but when I read of all these deaths, I wanted to go there. When I arrived the battle was over, but I could see many wounded people, which deeply affected me.

In 1964, there was a huge flood and I became the head of a committee to rescue the victims. I led a team of rescue people in five big boats. We journeyed to a very remote area to bring people food and medicine, and since the war was going on I had an opportunity to have further first-hand experience with the battlefield. We were told, “You cannot go to that area. On the other side of the mountain they are fighting.” I was warned that Red Cross workers from each side were being killed—Communist Red Cross workers had been shot by Nationalist soldiers and Nationalist Red Cross workers had been shot by Communist soldiers.

Fortunately, in Vietnam everybody is Buddhist—whether they practice or not, they are Buddhist. If you wave the Buddhist flag, both sides respect that. So, with our five boatloads of food and medicine, we went upriver into the mountains where they were fighting. When the bombs dropped, we stopped and sat quietly and breathed. Some of us were very afraid and jumped into the river to hide from the bombs. But I had a very strange conviction. I said to myself, “If God exists and Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva of great compassion, exists, they must need me, because God is love and Avalokitesvara is compassion. People are suffering and nobody is helping them. They need me, so they will protect me.” I believed they would protect me, that they would make the bullets go in the other direction and miss me. I sat there quietly and said, “I will be your instrument, to go and help those who are in need. Help me to avoid trouble.” I sat there and breathed quietly and peacefully. At that moment I had a vision that I was part of Avalokitesvara and I had no fear.

We arrived in a village which had just been the scene of a big battle. There was destruction everywhere and many wounded people. We bandaged them and gave them medicine until it ran out. Then I arrived at a hut where a woman said, “Oh, sister, my child is covered in blood. Help us save her!” She looked at me like I was God. But I thought to myself, I am not God. I knew that without medicine, I couldn’t do anything. But I knew that if I told her that, she would suffer even more. So I said, “Give her to me.” I held the baby in my arms, covered in blood, and I said, “Come with me.” We walked for about a mile. Halfway, the baby died. The mother cried and held the baby, then I held the baby for awhile. At that point, I became desperate to try to do something. I knew that we must let people know about the real effects of war. That is why I decided to call for peace.

What was your first experience with the West?

I first came to the West at the request of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam—to call for aid for war victims in Vietnam, and of course, to call for peace. When I arrived here I saw many scenes from the war in Vietnam on television, but I realized that these images were not the war. They were movies. So I understood right away why people continued to support the war.

Today, it is the same. People see a lot about Iraq on the television, but what they see are movies. To know war, you must run under the bombs. You must live in fear that you will be attacked and the bombs will drop on you, or that a suicide bomb will blow up one of your loved ones. On television, war is just an image and after you see it, you go dancing and eating. The image has nothing to do with reality. When you hold a baby covered in blood, then you know war.

What did you do as the war worsened and expanded?

After 1968, the war was no longer confined to the countryside. War had arrived in the big city. In reaching out to help others, I had always tried to do the things that people despised doing. They enjoyed the good things, but I tried to do the dirty work. When the war arrived in Saigon, everyone became a social worker, helping war victims. On every corner there were corpses of dead soldiers, both Communist and government. The Red Cross had no way to pick them up because the guerrillas were waiting around the corner to shoot them. Many Red Cross drivers lost their lives. I remember people in my School for Youth for Social Service who said, “We are doing humanitarian work. Why do you have to volunteer to pick up dead bodies?” And I said to them, “If no one removes all of these corpses, an epidemic will spread through the whole city. So we have to do this, the dirtiest work.”

Once again, when you bury a corpse you come to know war as it really is, not as it is in the newspapers and on television. When you approach a rotting corpse, it smells terrible. We had no chemicals such as they use today. I almost vomited. But I did the work because I was committed. I did that work all day long. I would look at the faces and I would think, “Alive you are like this and dead you are like this.” It was a very good meditation on life and death. But I had trouble eating. I could only eat white rice and salt. Everything else smelled like corpses to me.

How did you decide to become a Buddhist nun?

The Buddha said, “We don’t have a separate self. Our self is made of many elements.” The first element that contributed to my becoming a nun is probably my family. My grandfather was a very generous man who always tried to help poor people, even though he was not rich at all. He was a middle-class farmer. My father came from a large family. He had nine brothers and sisters and many cousins. When he grew up, he took care of all of his cousins and his nieces and nephews. So it is natural for me to feel that we have to do something to help.

As I grew up, I would wonder, “Why do I have a good situation? When I am hungry, my father can give me something to eat. When I want to be educated, some people can give me an education. I have to work hard to get into a good school, but others have no chance at all.” So with these thoughts in mind, I decided to help children in slum areas. They had no education. Not because there was no school around, but because they didn’t have a birth certificate. I did a lot by myself to help other families, and then my younger sister worked with me and other university students joined with us as well. In the end, we had quite a big group.

Around this time, I met with Buddhism, but it was not through Thich Nhat Hanh. My first teacher was Thich Than Tu, who is now a very famous Zen master. Thich Than Tu said, “You have done wonderful work, but that is merit work. It means you will be reborn in the future as a princess or into a very wealthy family.” This made me very angry and I told him, “I don’t want to be a princess. I don’t want to be wealthy. I want only to be fair to these children. I want to offer better conditions for these children, so they can grow up decently like me.”

Then, he said, “Anyway, you do the good work you are doing and it will bring merit. But you must learn to have insight.” In fact what he said is correct, but maybe he was not skillful in his explanation. So, when I met with Thich Nhat Hanh, my second teacher in Buddhism, he said, “Yes! You have to do both types of work. But you use your insight, your intelligence and deep looking in order to do the work you are doing properly, correctly, effectively. Without meditation, you cannot be calm. Without mediation, you cannot have a calm, clear mind that allows you to work beautifully.”

You have to practice in order to have calm, stillness. When you have calm and stillness, you can help countless numbers of people with ease. If you are irritated, you are unmindful and you will make one mistake on top of another mistake on top of another mistake. Thây [Thich Nhat Hanh] said that explaining why you do something is the dualistic way and that the non-dualistic way is, “The more work you do, the more you learn from your experiences and then the better you do it.” So, when I met with Thây and he told me that, I knew that we could use Buddhist principles to start some kind of nonviolent revolution. The basis of it would be that you help yourself by being calm, looking deeply, and then learning to do better.

Based on this thinking, we set up the School for Youth for Social Service. First, we gathered three hundred young people to be trained as medical aides. By that time a medical student friend of mine who had worked with me before had become a doctor and he helped to form our first medical group, made up of three doctors. They taught the students basic medical skills. The students also developed agricultural skills so that they could plant food and prevent farm diseases from killing livestock.

How did all this lead to your becoming a nun?

When I do something, I want to do it totally. So if I was a Buddhist, I wanted to become a nun, but not like the nuns I had seen growing up. The nuns at that time didn’t do anything! They would just sit. They would do sitting meditation all day long or they would chant a lot. But I felt that chanting alone would not bring relief to me or to starving children. I did need to sit in order to be calm enough to help people, but there was no nunnery that allowed you to do both. So I, and a number of my friends, decided to save our money and set up our own nunnery without even informing Thây. We were New Age nuns!

Much of the work we did with the School for Youth for Social Service was destroyed by war. So Thây had gone to the United States calling for peace. I knew that without him, we could not set up a nunnery. We could not shave our own heads! [Laughter] We needed a teacher. So at that point, my nunnery project was dropped. Meanwhile, my first teacher said, “I am stuck,” and he closed his door for many years and said, “When I see something, I will open the door.” He agreed that we needed to have a new nunnery, but the war continued to rage on and there wasn’t much we could do. So, the Unified Buddhist Church sent me to other countries to seek aid for war victims and to get help in stopping the war. I left Vietnam.

In the West people said to me, “You can’t become a nun because here the people are Christian. If you shave your head, maybe they will feel a little strange and they won’t think you’re attractive. You look like a young pretty lady. You have very long, beautiful hair, so people will like you.”

I traveled widely and talked to people and gained a lot of sympathy for our cause. I received many donations for hungry children, for relief and peace work. Many peace activists loved me.

Since it seemed to be working, I decided to become a nun without form. I lived a very frugal, simple life. I was vegetarian. I slept on the floor, in a sleeping bag. My life was like a nun’s life, but without the form.

Later, when I met with the abbot of a Buddhist temple, I found that she was younger than me, but her way of walking was so peaceful. I could see then that the form helped the contents. Sometimes without the form you may feel, “Oh, I am not a nun” and therefore can act in an agitated way. But being a nun, well-trained with the form, she had to walk mindfully, she had to speak properly. I saw that even though she was younger than me, her peace was greater than mine. So I decided that perhaps I would have to be formally trained as a nun.

I finally decided to shave my head in 1988. Very late. By that time, I had a history of practice, but I began putting the practice into every step. Every step is very important. Every morning in the training, I would touch my head and see that all of my hair was shaved and remember that I also shaved all of the jealousy, competition, fame and desire to be appreciated by people. We don’t need any of these things.

My name, Chan Khong, means true emptiness—empty of a separate self and full of everyone. If I am like that, it is because the Vietnam War taught me a lot. Many of my fellow countrymen died under the bombs. The woman with her baby covered in blood taught me. The baby taught me. Many things taught me. I am nothing. I am just a linking point, so people can learn. But even so, my ego still continues to be big. I have to touch my head, I have to remind myself, “You shave away all of these things! Don’t be so proud when people appreciate you!” They are appreciating the work of many people and I am only the link that brings it together.

To be a nun, it helps to have the form. This is very important. Nowadays, in Plum Village and Deer Park Monastery, I advise many young women to become nuns because the form and the guidelines of the practice will help them. But the point of this practice is not to lock oneself in a nunnery and not look outside. We can help in many ways, directly and indirectly. A nun can do social work directly, and I have done a lot of engaged social work, humanitarian work. But I also now give advice to social workers in Thailand, Bangladesh and France, so they can do the work that is needed. I spend a lot of time finding sponsors for hundreds of orphans.

I help people with family problems. People can suffer a great deal when there is misunderstanding between them and their father or their wife. I listen to them and help them reconcile with their wife, their children or their parents. As a result, all of them become so enthusiastic about the practice that they give me $10,000 to help hungry children. I don’t help people so they will give $10,000, but I feel that when people are at peace, they are happy and they are very generous.

The Prajnaparamita Sutra says, “Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form.” Since your name means true emptiness, can you say something about what that means?

Emptiness in Buddhism means empty of something. For example, when you say that you are eating, you have to eat something. You cannot eat nothing. So, what are you empty of? You are empty of a separate identity. My name means that I am not a separate identity. “Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form” means that each thing inter-is with every other thing. It is the recognition of a very deep interconnection.

You cannot be happy by yourself. Your happiness depends on the happiness of the person who lives alongside you: your son, your daughter, your partner, your neighbor, your co-worker. If we know this interconnection, we will try to live not only to make ourselves happy but also to make our daughters and sons and everyone else happy.

There’s a story I tell when I teach the children in Plum Village about the Prajnaparamita. At the beginning of the story a grandma recites, “Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form.”

A little child then says to his father, “Tell me, what does this nonsense mean?”

The father replies, “It means that we are deeply connected, just as we have a hand of five fingers. Here is your grandmother, here I am, here is your mother, your sister, your brother. We are five. If one finger is cut, do the other fingers suffer? Yes. So, if I have a car accident, do you suffer? Yes. So, we inter-are. We are deeply connected. The suffering of your self is my suffering and the suffering of grandmother is our suffering. If you want to be happy, you have to make grandmother happy, sister happy, father happy.”

Then, the little girl says, “Father! Does this mean that when my sister took my shoes and destroyed them and destroyed many of my belongings, that she is destroying herself?”

“Yes,” the father answered, “She is destroying herself. If she makes you suffer, she suffers too.”

At the end of the story, the father goes back home and he is upset because there is nothing to eat, and he and his wife start to quarrel. The little girl says, “Father is mother. Mother is father. Because ‘Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form,’ father is mother, mother is grandmother, grandmother is you, you are your sister and we are all one hand. And if one person hurts, all hurt. So, grandma is you and you are me. Mom, you are daddy, daddy is you. We are not different. If you suffer, we all suffer.”

The father and mother stopped quarreling and said, “Thank you! Thank you for reminding us.”

What has been your experience being a woman in Buddhism? Is it more difficult as a woman, and is Buddhism changing in this regard?

When I was less deep and mature than I am now, I was also very rebellious. I protested, “It’s not fair!” In my book, I tell a story about how I wanted to become a nun and practice Buddhism twenty-four hours a day. I didn’t want to just come to the temple once a week. But when I came to the temple, I saw many nuns living in the traditional way. I was told that a woman has very heavy karma and needs to practice in order to be reborn as a man in the next life. And then after that they will be liberated. I said, “I don’t need to become a man to become liberated! [Laughter] I am free now, or not at all. I am not sure that we have a next life anyway.” At that time, that’s what I believed.

Then, I looked more deeply. I saw that you cannot compare a magnolia with a dahlia. Each person is a species on earth that has a specialty. Usually women—the majority, not all—have a lot of civility and refined character and calmness, even though they may not know Buddhism and they don’t practice mindfulness. They are calm for the most part. But not all women are like that, including me. I am very special. I am not like that. I have the character of a man more than a woman. In many families the wife looks like she doesn’t do anything, but she does everything! She organizes everything. She always pretends that her husband is the director, but in fact she is directing things—especially in Vietnamese families. Many women are very talented. They call them “home minister” in Vietnam. Even though they are in the lead, when there are guests they always step back and pretend that they don’t do anything. But in fact, they are very powerful.

Men, on the other hand, have done a big job on a big scale, so I think that men and women can complete each other. That proves, for me, that there is no distinction between man and woman. When you have a very refined character, then you have to find a partner who has the opposite character in order to complete what you need. So if you have a very fine woman, a very powerful man will complement her. Of course, in society nobody thinks that way and sometimes women are oppressed and so on. I cannot define everything and say how it should be, but at the appropriate moment I try to act in the most skillful way so that there is no discrimination.

In many religions, at the beginning there is a person who has had great insight, like Jesus or Siddhartha Buddha, and they see no discrimination. All of the words of such great teachers, though, do not get written down word for word. The society we grew up in is male-dominated, so they put a lot of things into the religion that say that women have no rights to perform the mass in the church and so on. But I think if we asked Jesus he would say, “No, women can do it.” During his time, though, nobody asked that question, or the answer was left out.

In India, until the Buddha appeared, spirituality was reserved for men. There were many monks but no nuns. In Hinduism, your youth—lasting until you are thirty-five or forty—is for enjoying life, having sex and having children, having fame and a career. After forty, you find a spiritual life. That is why the Buddha’s father did not want him to become a monk: He thought he was too young. When he did became a monk, his first group of practitioners were only monks, but suddenly his stepmother and his former wife wanted to become nuns. This was too new an idea in India, though. Nobody thought a woman could become a spiritual teacher. It was impossible to imagine!

Eventually, orders of nuns developed and the Eight Rules of Respect for a woman to be accepted as a nun in Buddhism were established. You might think this means that in Buddhism there is discrimination against women. The Buddha did not discriminate. He accepted princes and princesses and untouchable people, the poorest, most humble workers. But in the society of 2600 years ago women were not supposed to be spiritual teachers even though some of them wanted to be. So it’s easy to see why special guidelines were needed. The Buddha was afraid that out of habit someone regal like his stepmother would say to an untouchable, “Go and serve me.” So, it became a rule of the community of the Buddha to accept women, with the condition that even if you are an old woman, if you see a young monk you have to pay respect to him. Even if you are already a practitioner for five years, if a young monk has just arrived and is just ordained for a few weeks, you also show respect to him. That is the beauty of respect. I am not against that.

What do you think about the way Buddhism has come to the United States, and how do you view the development of Buddhism here?

If we follow the traditional approach of Buddhism and try to make many people in this country understand Buddhism fully, it will take longer. They are born Christian or Jewish or they are non-believers. You would have to uproot them and ask them to become Buddhist, which would take a very long time. With me, for example, I don’t feel a family connection at all with Tibetan Buddhism. I am Asian, but I am not comfortable with all of the color in Tibetan Buddhism. However, the colorful part is from Tibetan culture. It is not Buddhism.

Japanese Buddhism is very strict, very pure and very sober. It is rigid. That is Japanese culture. Years ago in Japan you didn’t need to know Buddhism. Every house was neat and the view was sober. That is their culture.

Thây’s teaching is very skillful because he doesn’t want to uproot people from where they are. They can be non-believers, they can be Christian or Jewish—provided that they go in the direction of understanding, love, acceptance, tolerance and embracing each other. Non-discrimination. Mindfulness is the Buddha! The Buddha said that a person who has great mindfulness, who can be very concentrated and look deeply into the present moment, sees everything clearly and correctly. That is what a buddha is. So, instead of using the word “buddha,” Thây uses “mindfulness.” With mindfulness, a non-believer can still say, “I am mindful. My mind is fully in the present moment.” If you are Jewish? Fine! You can say, “I can be mindful while I am Jewish.” You can be mindful while you are Christian.

In our meditation hall there are three words: smrti, which means mindfulness; samadhi, which means concentration; and prajna, which means insight. When you are mindful, your mind is very concentrated. You see very deeply. And when you see very deeply, there is prajna. You look very deeply, to the root of the path, to the outcome of the future. If you do this in a very skillful way, you don’t need to be a Buddhist. You only need to practice to be mindful and concentrated and have deep insight. Then, you are already a great person and you can bring happiness to people in the world.

If everybody tried to practice that and helped to spread that practice, we could make this world more compassionate, more understanding and more loving without people needing to feel, “Oh, I lost my son because he has become Buddhist. I lost my daughter because now she has become Buddhist.” Everybody can feel safe and happy. One can continue to be Christian, but a more profound Christian. To be a Jew, but a more profound Jew. To be a non-believer, but a more profound non-believer.