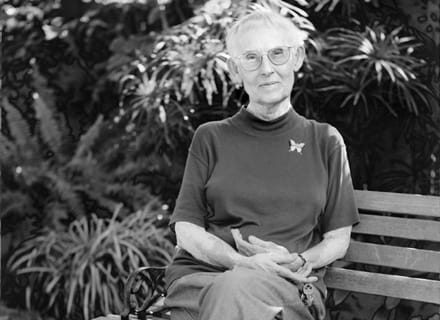

On July 2, a memorial for Charlotte Joko Beck was held at the Zen Center of San Diego (ZCSD). Fifty people (including several roshis) were in attendance.

Among those who spoke at the memorial was Elizabeth Hamilton, who had for some time studied with Beck. She offered a history of her former teacher’s somewhat revolutionary teaching years — starting with Beck’s break with Maezumi Roshi, her teachings in the following two decades, and then her break with Hamilton and her spouse and co-teacher, Ezra Bayda, after retiring from ZCSD.

Comments from Elizabeth Hamilton:

On June 15, Charlotte Joko Beck joined the ancestors. Joko was the first teacher at ZCSD, and her teaching vocation flowered here for over two decades.

A memorial like this marks a milestone. There’s also another form of memorial: each of us, in the solitude of meditation, can reflect on John Welwood’s powerful reminder that what we fail to grieve, often turns into grievance.

Some of you were quite close to Joko, and have had a period of five years to grieve. Others of you may not have known Joko. Today is almost five years to the day since Joko retired from ZCSD, and moved to Prescott, Arizona to live with her daughter Brenda and son Greg.

Soon after leaving ZCSD, Joko broke off her association with ZCSD, Ezra and me. She requested in a public letter that we not imply that we, or ZCSD, teach the things she taught.

This is a poignant talk to give, and I will do my best to steer the razor’s edge of honoring Joko’s wishes while still commemorating her life and her contributions. I’ve run these remarks past Ezra, and he feels free to add things.

To put things in perspective, we’ll start by mentioning a few Zen traditions that may be unfamiliar to some of you:

dharma transmission and lineage. Today we have several co-teachers with us, from Joko’s original lineage or transmission and teaching line, the White Plum: Nicolee Jikyo McMahon of Three Treasures Zen Center, and Seisen Saunders from Sweetwater Zen Center. Nicolee, Seisen, Ezra and I were all students of Maezumi Roshi back in the day. Ezra also studied with Maezumi Roshi’s teacher Koryu Roshi in the early 70’s. All of us received dharma transmission, and authorization to teach, through various dharma successors of Maezumi Roshi.

White Plum is the name Maezumi Roshi gave to the American amalgam of Japan’s Soto, Rinzai and Sambo Kyodan lineages. He had received dharma transmission in all three of these usually separate traditions.

Now for a little background on how Joko came to ZCSD. This center’s origins go back to the Black Mountain Zendo in Del Mar in the 70’s, a sitting group that met in the home of Chozen and Michael Soule. When they moved to ZCLA to study with Maezumi Roshi, six of us moved into the house to keep the sitting group going.

From about 1979-1983, three ZCLA teachers took turns coming to BMZ to lead retreats, or sesshins: Maezumi Roshi, Genpo Roshi, and Joko Sensei. At Maezumi Roshi’s request, I became BMZ’s resident monk.

In 1983, soon after receiving dharma transmission from Maezumi Roshi, Joko received permission from him to return to San Diego, where she had raised her children.

We moved from BMZ to Pacific Beach, and Joko became the first teacher. Shortly after coming to ZCSD, Joko broke off her ties with Maezumi Roshi and ZCLA. He was going through a difficult time. I had already taken a leave of absence from our teacher-student relationship, hoping to encourage his healing path; others stayed with him, for the same reason. Despite this leave of absence, we retained a close connection over the years.

I became Joko’s student during this time. Soon after her break with ZCLA and Maezumi Roshi, Joko founded the Ordinary Mind Zen School. Diane Rizzetto and I received dharma transmission the same week in 1994, and Ezra in 1998. Diane, who is now also in White Plum, has said, “dharma succession is an acknowledgement, not something that can be given.”

Joko continued at ZCSD in her prime, from her first book in the 80’s until the end of the 20th century. She was considered somewhat of a revolutionary in the Zen world, insisting that Zen training must directly address our conditioned reactions, the painful unfinished business that causes us to see life through what 18th century Zen ancestor Menzan Zenji called “the frozen mass of emotion-thought,” his name for ego-conditioning. By bringing meditative awareness to our unresolved conditioning, we can discover that our ego-self, like everything else, is a form of emptiness.

Joko also taught that occasional moments of insight are relatively insignificant in themselves, since they are usually rapidly eclipsed by the re-emergence of old habit patterns that lurk in the shadows. They are rarely illuminated by

so-called “enlightenment experiences.” Far more important than such experiences is whether practice insights are implemented in daily life, by living compassionately, as-if-awake to our interconnectedness with one another — as well as continuing to clarify our conditioning, when it is activated.

In her heyday, Joko taught that we can refrain from allowing painful situations to lead us into unskillful words or actions. All of these teaching are now widespread, in the Zen world and beyond. They are her legacy from the ZCSD years.

After Joko’s July 2006 retirement from ZCSD, & subsequent letter to us, we didn’t hear from her again. We’ve written regularly, to express our appreciation, and remorse for whatever pain we may have caused inadvertently.

Three years ago, after deep reflection, Ezra and I accepted the invitation of White Plum to renew and reaffirm our lineage and transmission connection. The ceremony, in the ZCLA Ancestor’s Room, was officiated by ZCLA’s abbot, Roshi Egyoku Nakao. This step reflects our affinity with White pPlum, and our appreciation of Maezumi Roshi, whom Ezra and I consider our first Zen teacher.

By the way, Egyoku and Diane both said to mention that they would love to have been here today. However, Egyoku is in Seattle, and Diane is in Boston.

Today’s words are intended as an appreciation of Joko’s contributions, to ZCSD and the larger Zen community.

So much remains unsaid. My relationship with Joko spanned almost forty years, starting with being colleagues at UCSD in 1967, up until the final chapter, teaching alongside one another at ZCSD for 14 years.

Such connections can hardly be defined by the last few difficult years.

A colleague of ours visited Joko in her last weeks, and asked her what she now sees as most important, saying that her response was kindness.

As today’s reading, Relying on Heartmind says, “Heartmind has the totality of space – nothing lacking, nothing extra.”

In the depths of heart-mind, all is reconciled.

When direct words are no longer possible, we can still express our appreciation to Joko, and all the ancestors, by doing our best to walk the path of awakening that they have facilitated. With the encouragement of our aspiration and vows, community, and a clear sense of practice, we return constantly to the present, rather than dwelling in the past.

This is our living memorial. Our gratitude is irrevocable.