The Spring 2024 Buddhadharma is dedicated to a set of yogic practices once considered highly secret due to their perceived incompatibility with aspects of monastic life. Yet the Six Dharmas represent the heart essence of the Buddhist tantras and an accelerated path to buddhahood based on activation of the body’s subtle nervous system, configured as a constellation of radiant energy plexuses (Sanskrit: chakras) and flows of vital energy (prana) coursing through channels (nadis) between the pelvic cavity (sometimes inaccurately thought of as the base of the spine) and the crown of the head. The ecstatic consciousness that these practices induce fuses with experiential awareness of the interconnected nature of all phenomena during phases of waking, sleeping, dreaming, and dying, thus leading to liberation from subconscious conditioning and its attendant dissatisfactions.

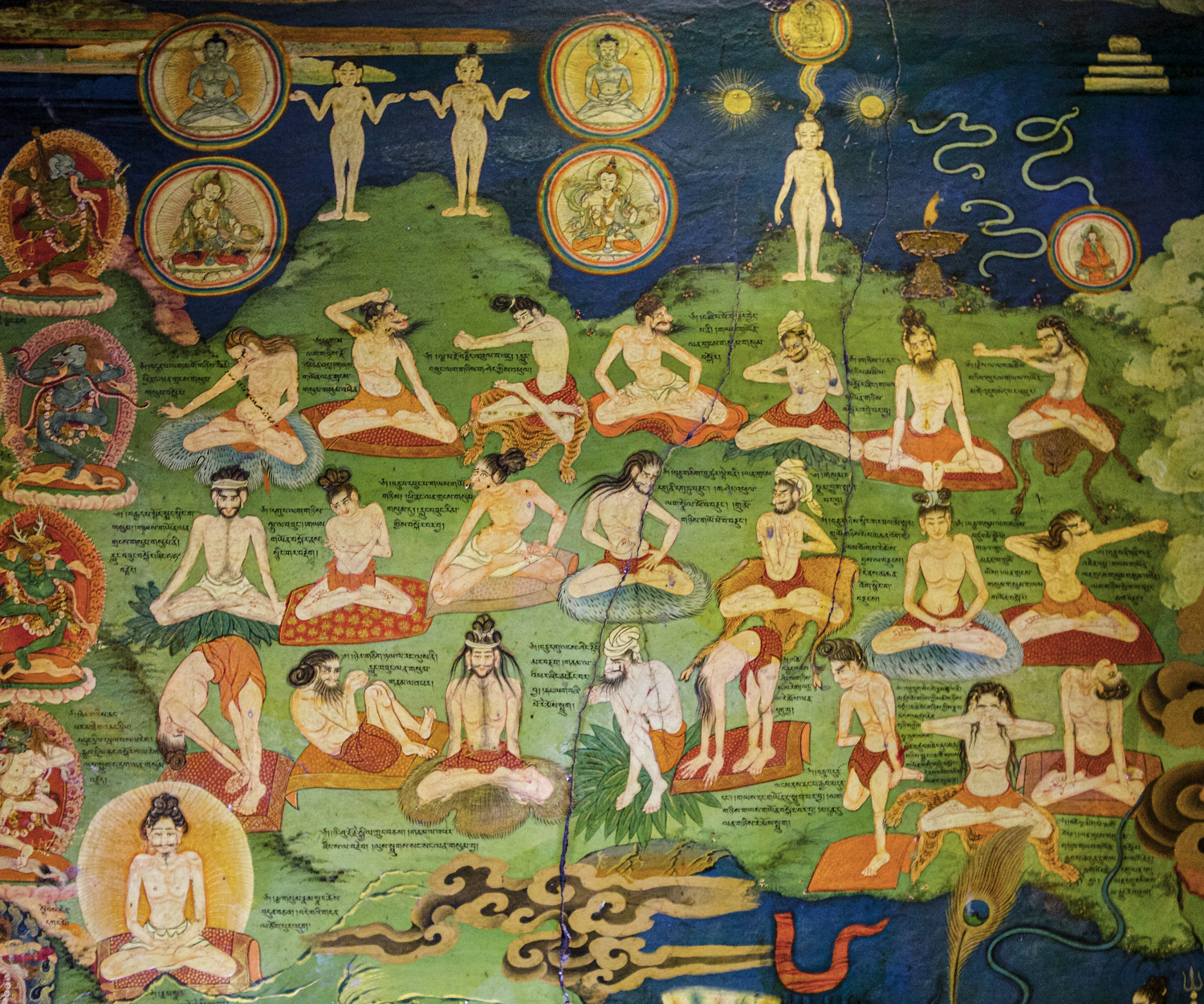

The earliest compilation of the Six Dharmas is attributed to the Bengali mahasiddha Tilopa (988–1069 CE) and arguably draws on the sixfold yoga presented in the fourth-century BCE Maitrayaniya Upanisad—one of the oldest known descriptions of yoga theory. Presentations of the Six Dharmas typically focus on the foundational “root” practices of blissful heat, illusory form, and luminosity, and auxiliary “branch” practices of transformative dreaming, consciousness transference, and navigation of end-of-life and postmortem experiences. These are all explored in this issue. As an integrated whole, they lead to the recognition of our embodied selves as provisional manifestations that can be altered through intention and conscious interventions during recurring cycles of day and night and the larger transitional phases of life, death, and rebirth.

Tilopa transmitted these core practices of the Indian tantric Buddhist tradition to Naropa, the illustrious eleventh-century Indian scholar who had left the Buddhist monastic university of Nalanda in search of more inclusive forms of knowledge. The Six Dharmas and their culmination as Mahamudra—an openness and luminosity of being expressed within all activity and beyond conventional distinctions between samsara and nirvana—subsequently became the foundation of the Kagyu, or “whispered lineage,” that Naropa’s Tibetan disciple, Marpa Chökyi Lodrö (1012–97) established in Tibet after carrying the teachings of the Six Dharmas from the jungles of eastern India across the Himalayas to his home on the border of Tibet and Bhutan. A nearly identical contemporaneous transmission of the Six Dharmas, originating with the female Kashmiri adept Niguma, was introduced in Tibet by the yogin Khyungpo Naljor and became the basis of the Shangpa Kagyu Buddhist lineage. As Niguma summarized her teachings: “Dwell undistractedly in the mind’s innate luminosity . . . in the infinite expanse of reality, there is nothing to cling to or reject, neither meditation nor non-meditation.”

The original transmission of the Six Dharmas, both in India and Tibet, occurred outside any monastic context and represented teachings that could be readily applied by householders and itinerant yogins. As indicated in numerous tantric texts, successful practice of the Six Dharmas—including karmamudra, or meditative union—leads to experiential realization of Mahamudra, the continuum of luminescent awareness that encompasses all aspects of life and pervades the four states of waking, dreaming, sleeping, and dying.

Tilopa clarified the nonconceptual wakefulness of Mahamudra in a six-point teaching that condenses the intention of the Six Dharmas: “Don’t imagine; don’t think; don’t deliberate; don’t meditate; and don’t analyze,” he instructed. “Remain in the mind’s natural state.” Carrying the Six Dharmas into our daily lives thus involves approaching all experiences openly as negotiable dreams, empty of abiding essence. As Tilopa further clarified in his Mahamudra Instruction to Naropa in Twenty-Eight Verses: “Beyond all mental images the mind is naturally luminous. Follow no path to follow the path of the Buddhas; Employ no technique to gain supreme enlightenment.” Nonetheless, as the essence of Tibet’s inner tantric tradition, the Six Dharmas offer a timeless, integrated system for recalibrating the body-mind and gaining conscious control over normally autonomic psychophysiological processes.

As for the traditions of secrecy that once hindered the transmission of the Six Dharmas, Tilopa said in his Song of Mahamudra: “The real vow of samaya is broken by thinking in terms of precepts, and it is maintained with the cessation of fixed ideas. Let thoughts and ideas rise and subside like ocean waves. If you neither dwell, perceive, nor stray from the ultimate meaning, the Tantric precepts are automatically upheld, like a lamp which illuminates darkness.”

The liberating methods of the Six Dharmas provide a path beyond habitual discontents through their active embrace and transfiguration of everyday natural phenomena and events. Approached with discernment, the practices can dispel the illusion of a separate, autonomous self and reveal our magical and inextricable unity with all of life in an ever-expanding, interconnected cosmos. As Naropa himself proclaimed, “Through practicing these secret yogas, vitality and wisdom circulate through the body and, in this very lifetime, one arises as Buddha Vajradhara,” the primordial embodiment of supreme awakening.