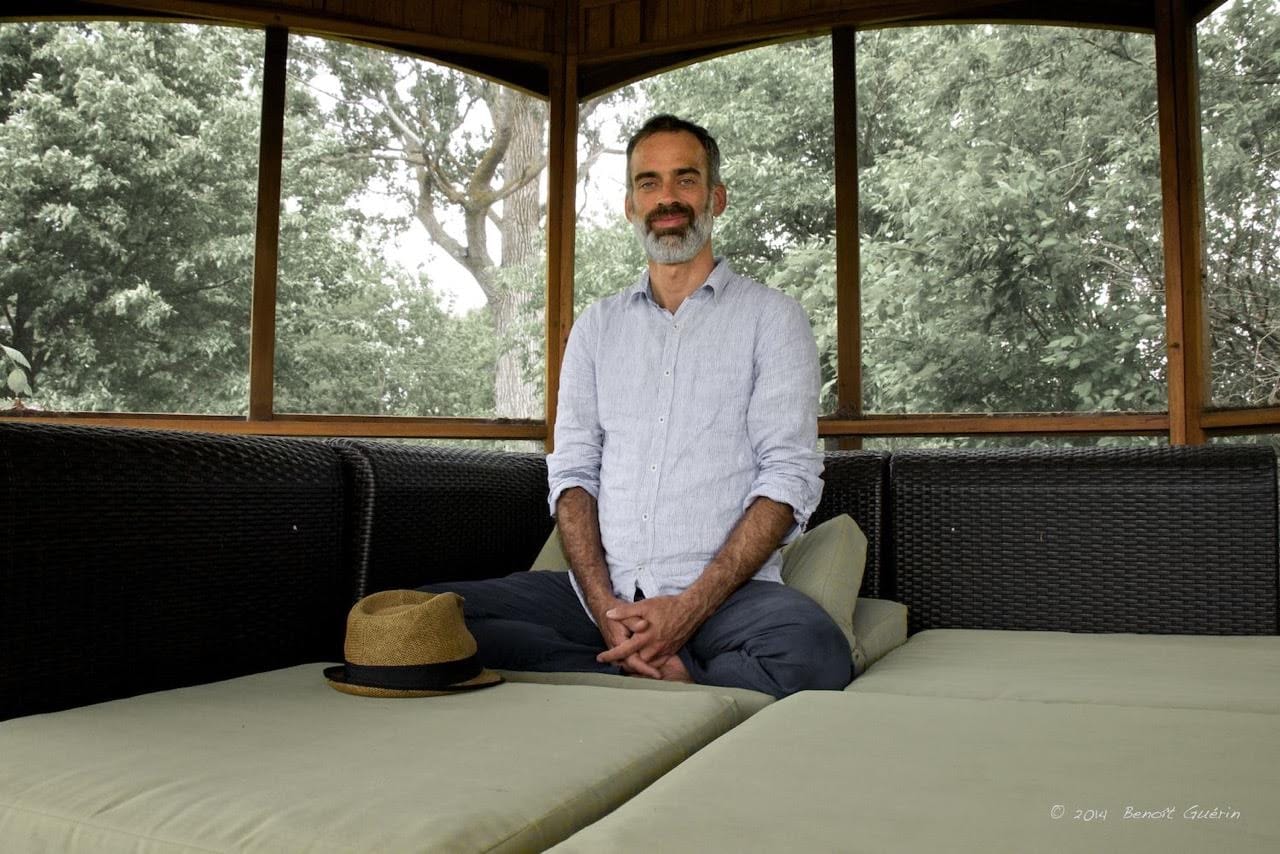

It was 1995 and Pascal Auclair was a handsome 25-year-old actor in Montreal. His life changed, though, when his doctor uttered the words, “You are HIV positive.”

“It was as if the building had crumbled beneath me,” says Auclair. “It was like things that were solid were no longer solid.”

The doctor told Auclair he had only a few years to live, and that his immune system was completely gone. “But I didn’t feel sick at all,” says Auclair. “I was supposed to be going to an audition for a beer or pizza commercial, but that felt a little gross or vulgar after this news. So I thought, ‘Pascal, maybe you should just drop acting.’ And then I went, ‘Oh, there’s a whole new identity I’m going to have to craft.’

“I had thought of myself as youthful, handsome, and eternal,” he says. “But I had seen people with this condition age quickly, be very sick, and die. A year later, when I encountered the Buddhist teachings of the four messengers, of the Buddha meeting sickness, old age, and death, I thought, I know that experience.”

I entered the real groundlessness of grief, but in a way that was nonreactive and curious about the process.”

“A few days after the diagnosis, there was a lot of gratitude,” Auclair says. “I felt so lucky to have studied theatre and traveled all over the world.” However, he then faced six months of deep depression, shock, and hurt. On a later trip to Thailand, Auclair heard about a monastery that offered weeklong silent retreats with meditation. “Right away, in the practice, I was home,” he says. “Everything made total sense, answered a lot of my questions, and gave me tools.”

Auclair signed up for a three-month silent retreat at the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Massachusetts. He calls the retreat a kind of heaven. “It was 90 days of people cooking for you, of nature, and of silence. It was amazing to see the fall, the leaves changing minute by minute. To become that quiet and that still and that touched by nature. And then to get the dharma every night.”

A huge old oak tree was felled by a windstorm on the property during the retreat. “I’d become very sensitive and when it fell, I got back into the grieving phase of HIV, where I needed to be,” says Auclair. “It was like it symbolized the fall of my youth, the fall of my health. I entered the real groundlessness of grief, but in a way that was nonreactive and curious about the process.”

Auclair’s retreat was led by Joseph Goldstein, a cofounder of IMS. “Joseph taught me how to hold vulnerability. I spent hours watching workers cut the tree and remove the pieces. I was seeing something being deconstructed. And I was deconstructing the experience of being Pascal at the same time: What is Pascal? A series of mind states. What is Pascal? A series of sensations. What is Pascal? A series of impressions, a series of identities.”

Auclair has been immersed in Buddhist practice and study for twenty years now, and mentored with Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield at IMS and at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in California, one of the centers where he now teaches. He says that facing death is the most important spiritual teaching. “A lot of spiritual journeys are based on the denial of death, a heaven, an eternity so you don’t have to face death head-on,” he says. “But we must face it. We call the ‘big death’ the moment when the body dies. And people say, ‘Oh my god, they died, what a horrible thing.’ But to me this is a symbol for everything that happens in our lives—this impermanence, this not knowing what’s coming. The big death serves to inform the small deaths—the death of romantic relationships, the death of moments of beauty. It’s a conversation between both.”

“Facing death is a device for tenderizing hearts,” Auclair says. “So if I give a class, and I feel like I don’t have that much time to open hearts, I know one of the tricks is to talk about death. What we all have in common is that we’re going to die and we don’t know when, so how is that for each of us? When I ask that, we immediately drop down to another level. Now minds are open and we can have a real conversation. People are really aware.”

Auclair also uses death as part of his personal practice. “I notice how moments change and they disappear. In my tradition, at the end of sitting, the bell rings and we put our hands together. At that point, my hands are on my knees and I just take a moment to feel that experience. It is real, it exists: hands touching thighs. A second later, hands are not touching thighs anymore. There’s a beautiful encounter and then it’s gone. To notice that is the best practice to prepare for death.”

Auclair has replaced his fear of death with an intimacy with it. “It leads to a preciousness of things; a kind of portal to joy. And maybe later I’m going to freak out when I get really sick, because we don’t know what will happen. Everything is possible.”