Directly confronting death, it’s told, was the final catalyst that drove Prince Siddhartha from the luxurious shelter of his palace into the arduous life of a truth-seeking ascetic. The gritty fact of death set in motion the decisions that led Siddhartha to realize the state beyond death—as buddha—and teach others how to do the same.

Death as we generally experience it in modern entertainment culture, however, is not nearly so edifying. There is, of course, no shortage of increasingly gory and inventive depictions of death, but for the most part these scenes lack any depth of consequence or context. There are no means offered the viewer to confront the realities of dying as they’re actually experienced when death comes to our own homes.

Time of Death, a remarkably courageous and nuanced documentary series that debuted on Showtime Friday night (and will be re-run Sunday at 6pm), aims to change all that. Over six episodes, the filmmakers’ cameras (sometimes wielded by them, sometimes by the subjects themselves) allow us an intimate view into the dying process of eight Americans from 19 to 78, as well as the complex interrelationships among those in the dying person’s orbit: family (estranged and otherwise), friends (ditto), and caregivers, as well as health and end-of-life professionals.

Time of Death was earning a lot of critical praise before it aired, so we watched the first episode to see if it lived up to the hype. It did.

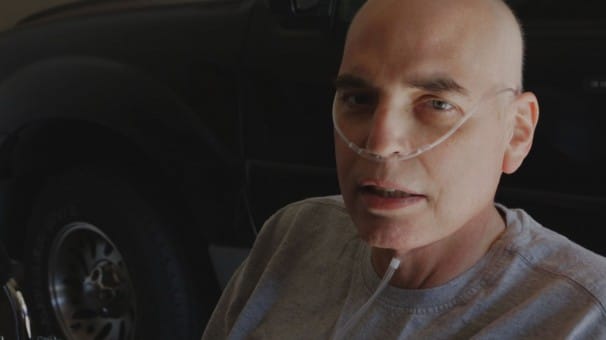

This episode introduces 48-year-old Maria, who has stage 4 breast cancer, and Michael, a Navy vet who comes off disarmingly nonchalant as he quickly succumbs to a different cancer. Beneath the bravado of gallows humor (“Death is a life-ending dilemma,” says Maria) we feel the intensity of the stress points when choices loom that can no longer be avoided. Will Maria assign custody of her two high-schoolers to their 25-year-old half sister, who seems barely able to take care of herself, or will they be forced into an outcome they express deep fear about: being taken in by their violently abusive father? Has Michael’s ex- wife reappeared just to hammer in a final spiteful nail, or to forgive him for his own abusive past?

We see all five stages of grief playing out in both storylines—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—but in ways that follow the unpredictable courses laid out by a host of attendant emotions, whether they be released or suppressed. As Michael’s hospice nurse observes, “There’s no manual for how to do this.”

That may be, but one does note the degree to which the subjects in Time of Death are taking control of the decisions concerning how they wish to die. Washington Post critic Hank Stuever astutely notes in his review that we are finally seeing a high-profile documentary addressing a significant generational trend:

“One of our great achievements in American culture over the last few decades has gone mostly, quietly unnoticed: We’re getting a lot better at death.

“Despite botox and youth worship, baby boomers and Generation X are changing the rituals and customs of a frank and noble exit. Funerals are more casual, celebratory in tone — with biographical videos, favorite pop songs and even a pair of Ray-Ban sunglasses worn by the deceased. Cremation is becoming a more popular and affordable option, dramatically shifting the definition of a final resting place. And enough of us now know first-hand that real angels and heroes work in the fields of hospice and palliative care.”

With the Buddha’s emphasis on the inestimable spiritual value of becoming clear-eyed concerning impermanence and the certainty that all that comes into existence will also pass away, Western Buddhists have long been on the leading edge of this trend. Our online summit, Death, Love, and Wisdom offers a wealth of Buddhist wisdom to help you relate to death and dying with fearless compassion.