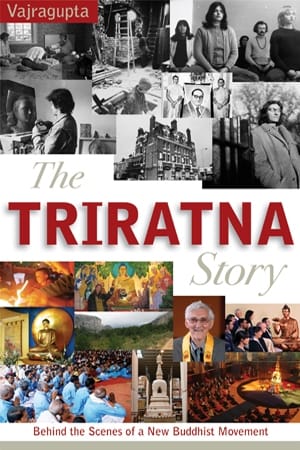

The Triratna Story: Behind the Scenes of a New Buddhist Movement

By Vajragupta

Windhorse Publications, 2010

220 pages; $13.95 (paperback)

Reviewed by James Coleman

Triratna Buddhist Community, formerly called the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, or FWBO, is not well known in North America, but it’s one of the largest Buddhist organizations in Great Britain and has an increasing international presence. For those not familiar with the group, this book tells a fascinating story of the growth of an important Buddhist movement. The author, Vajragupta, is a prominent member of the organization and it was published by Triratna’s own press, so don’t expect a hard-hitting exposé, but Vajragupta and the group as a whole do try to take a sincere look at their failings even as they celebrate their success.

The story starts in India, where a young Briton, Dennis Lingwood, left the military at the end of World War II and began a long spiritual quest. Although he studied with several Buddhist teachers and was given the name Sangharakshita, he never affiliated himself with any individual lineage, and eventually founded an independent Buddhist movement that combined elements from different Buddhist traditions.

Like other Western Buddhist movements, the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order had its roots in the counterculture of the sixties and seventies. But the FWBO was exceptional not only in its lack of affiliation with a particular lineage, but in its active pursuit of converts, and its intention not merely to spread Buddhism in the West but to bring about a fundamental transformation of Western society. The movement spread rapidly in Britain, and came to be based around “right livelihood communities,” which sought to support communal living by developing businesses based on Buddhist principles. In its early days, FWBO members had a reputation among other British Buddhist groups as being rather brash and standoffish, but this book is evidence that they, like Western Buddhism in general, have mellowed with age.

Triratna has proven to have broad appeal beyond Britain, and has chapters in numerous other Western countries. It is unique among major Western Buddhist groups in having attracted more members in Asia than in the West. During his time in India, Sangharakshita had several dialogues about Buddhism with B.R. Ambedkar, the famous political leader who sponsored a mass conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism among India’s outcaste Dalits. Sangharakshita spoke to more than 100,000 people who gathered to honor Ambedkar when he died in 1956, and spent as many as six months a year teaching dharma to Ambedkarite Buddhists from 1957 to 1964, when he returned to England. After the FWBO was firmly established in Britain, several of its teachers returned to India and started what is now a flourishing community within the Ambedkarite movement.

The Triratna Story is surprisingly short on details about the group’s doctrines and practices, but Vajragupta (Richard Staunton) does a wonderful job of bringing to life many of the stories of struggle and fulfillment of its members. He also makes a commendable effort to bring an open heart and a fair mind to his discussion of the scandals, crises, and problems that have rocked the organization.

The problems the FWBO had in the eighties at its Croydon Center in a suburb south of London will sound familiar to anyone who knows the history of the San Francisco Zen Center’s business operations when Richard Baker was abbot. As in San Francisco, young idealistic students were pushed to the breaking point, working long hours for low pay in order to turn a profit for the businesses owned by the center. The similarities go right down to the highly successful vegetarian restaurants each organization ran.

The Triratna community also has been the subject of some of the most serious complaints of gender discrimination made against any Western Buddhist group. During the seventies, there was a movement toward sex segregation in FWBO’s residential communities and businesses. The men’s organizations, which developed faster, seemed to receive more resources and exercise far more power than the women’s groups. There also has been strong criticism of the founder’s view that women are less inclined to commit themselves to spiritual practice than men, and especially of the views expressed by Subhuti, the organization’s second-most influential figure, in a 1995 book also issued by Triratna’s Windhorse Publications. Among other controversial claims in the book, Subhuti explicitly states that the spiritual capacity of women is inferior to that of men.

Like so many other Western Buddhist groups, though, Triratna’s biggest problems have been with sex. The prominent British newspaper The Guardian ran an article in 1997 in which it alleged that the FWBO had pressured some of its male members into homosexuality and that at least one of them had committed suicide as a result. Vajragupta tries his best to rebut those charges and those of a more vitriolic website created explicitly to challenge the organization, but he does take to heart the claims of one of Sangharakshita’s former lovers, Yashomitra, a respected, longtime member of the group. In 2003, Yashomitra published a letter stating that when he was eighteen he was pressured into a harmful sexual relationship by Sangharakshita, who was his preceptor and nearly forty years his senior. These problems have clearly been the subject of much soul-searching both by Vajragupta and the Triratna community as a whole. The book contends that they have learned some hard and valuable lessons from their mistakes, and it appears that the group has emerged the stronger for it.

What can the wider Buddhist community learn from Triratna’s experience, and from the other scandals that have accompanied Buddhism’s spread in the West?

On an institutional level, it is clear that any organization dominated by a single charismatic individual is more vulnerable to corruption and abuse than more democratic ones, and this may be especially true of religious groups that see their leader as more spiritually realized than the rank and file, and thus harder to judge. The unfolding history of Western Buddhism seems to point to the conclusion that the best organizational response to this problem is to rely on the leadership of a group of more or less equal teachers, rather than a single individual. Though students may be ill equipped to objectively evaluate the behavior of a spiritual teacher they idolize, other teachers have both the experience and motivation to challenge abusive behavior among their colleagues, who may, after all, be rivals for prestige and power.

This model has worked effectively in large Vipassana groups, such as the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Marin County, and that is the direction the Triratna community itself has taken since Sangharakshita began withdrawing from his day-to-day supervision of the organization. Of course, that is hardly an option for most small groups, but at least in areas that have a variety of Buddhist organizations, the overall Buddhist community can perform some of the same functions.

On an individual level, some would say that we need to take a more mature attitude toward our teachers, and to stop idolizing them and ignoring misbehavior. That is an obvious and reasonable suggestion, but it brings a serious problem. Many students have found it a privilege to be able to revere their teachers, and I think it would be a significant loss to Western Buddhism to abandon that ancient tradition. Perhaps we would do better to learn to extend some of that reverence to the malcontents and whistleblowers, for they are the ones who keep us honest and our organizations healthy. One of the best ways to avoid repeating the errors of the past is to study and understand them, and with that in mind I recommend The Triratna Story to anyone who is unfamiliar with the history of this group.