As Buddhist and mindfulness practitioners, we have an opportunity to understand the dynamics of racial suffering and the flesh we put on its bones. Honoring our relatedness, our belonging, and our impact is a necessity for awakening in general and for transforming racial suffering in particular—in our own hearts, and in our communities and institutions.

As an African American Western Buddhist practitioner and teacher, I have sat on my meditation cushion in silence, with hundreds of other yogis, ripening my capacity to live in gentle and wise awareness. I’ve done this, sometimes for months at a time, without ever speaking to the yogi who sat beside me, and within me there was great comfort in knowing that despite our differing paths, we had somehow landed on our cushions and were opening our hearts together. This, in my mind, is a miracle.

But over the years, participating in dharma programs mostly attended and led by white people, I often felt my heart quake and stomach tighten after hearing teachers and yogis speak from a lack of awareness of themselves as racial beings. I didn’t hear blatant racist comments with intent to harm. Rather, there was a more subtle obliviousness to whiteness as a collective and its privilege and impact, and an assumption that we were all the same or wanted to be. In those moments, despite my best efforts, I was reminded of race and of being invisible and would spin into a hurricane of anger, confusion, and despair, asking myself: Why did you come? What did you expect? Are you delusional? Why do you need your experience to be acknowledged here? Why don’t you wake up and stop kidding yourself?

Race has ricocheted on my practice in painful ways with regularity, and while I would have liked to avoid “going there” (dealing with racial ignorance and its pain again and again), oddly I recognized that “going there” was “being here.” While I was able at times through this precious practice to self-soothe, let go, soften, and experience this suffering with fleeting degrees of clarity and grace, there was something untouched and unsettled by this solitary inquiry that eventually ignited a desire for deeper understanding and collective exploration.

When we apply Buddhist teachings to Western culture, we must take into consideration the impact of our deeply rooted history of colonialism, racial enslavement, and exploitation. White dominant culture as a historical collective continues to benefit from racial injustice, knowingly or unknowingly. Western Buddhist practitioners and organizations are in denial if they believe they are exempt from the stain of this history and its persistent contribution to separation and suffering.

When we look around, we can readily see that most of the recognized Insight Meditation retreat centers are headed by whites and typically lack racial diversity. Added to this, and of delicate significance, is the fact that our practice is generally in silence. Subordinated cultures have a history of experiencing silence as oppressive, and exploring this tender territory on retreat is often misunderstood by white teachers. Much harm occurs for people of color when this pain is felt deeply and met by an inadequate response, within a formal structure, where personal contact is limited. This dynamic accentuates white dominance, denial, color blindness, and individualism; for people of color, latent experiences of oppression are intensified, and the environment begins to feel unsafe. Given this, and other examples like this, we can perhaps begin to understand why our sanghas, largely led by white people, may be chronically, racially, even appropriately divided.

Having taught in multiyear engagement programs such as Spirit Rock’s Community Dharma Leaders Program and the Dedicated Practitioners’ Program, I’ve seen many white practitioners express anger and discontent when racial suffering is directly explored, many of whom felt that focusing on race involved clinging to concepts and was therefore inconsistent with Buddhism. Some whites have been so upset that they have dropped out of the program altogether, saying, This is not what I signed up for. People of color have dropped out as well, saying the same thing but stating different reasons, namely that they were disappointed these programs were not safe or welcoming communities to engage in or begin to heal the realities of racial suffering. In such habitual stalemates, racial hurt and ignorance are further conditioned.

There are sincere attempts to bridge racial divisions within sanghas, but it’s often awkward—a dance between white delusion or guilt, and aversion experienced by people of color. For example, I hear white sangha members say, When I look at you, I don’t see race. As an African American woman, this well-meaning comment renders my experience invisible, my history whitewashed, my people at risk, and our relationship questionable. Not seeing race is privilege, and it’s not an option for me as a Black woman in America.

At the core of racial suffering is denial about our belonging—that is, our kinship and our membership in each other’s lives. The separation inherent in the entrenched patterns of racial suffering is not just a division of the races. The consciousness—or unconsciousness—that supports racial suffering cuts people out of our hearts, then has us try to live as if “cutting” does not hurt. We have come to accept this dismemberment as normal and move about our lives in search of spiritual freedom and contentment, as if we are not bleeding from the wounds of separation. It’s as if we were orphans in search of our family, not realizing that they are “the other”—the ones we despise, don’t see, or think we know. We have convinced ourselves that we can live with missing body parts—with some folks and without others—and still be whole, happy, and peaceful. But the reality is that we live in a state of pervasive unsatisfactoriness and confusion, not able to see or touch a deep sense of belonging, nor put language to it. We work harder at belonging because we only make use of a fraction of our wholeness and overcompensate with what remains: righteousness or avoidance that masks fear. We waste energy that our communities need to heal and transform. In these moments of dismemberment, we have forgotten that all of our parts matter.

Our challenge is to practice in ways that reflect tender and wise kinship with all beings. We must ask ourselves, how can we create a sangha that genuinely cares about racial suffering and belonging?

To begin—and we are always beginning—here are a few practical strategies that we can incorporate into our practice.

Set an Intention

Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is face.

—James Baldwin

There is no shortage of information on racial ignorance, hatred, and injustice—we need only Google it! Some people lack interest in matters of race, while others feel overloaded and burdened by it and need to shift how they hold the suffering. Delusion, aversion, righteousness, and distraction are just some of the common strategies that keep us from facing the deeper truth of racial suffering and from experiencing the intimacy of our shared and diverse humanity.

We must be clear in our intentions regarding what we want to wake up to, and then attend to them mindfully. We all need an intention beyond righteousness. Ask yourself, what is your vision of racial healing? Why is this important to you personally? What do you need to face up to and own in order to stay awake to racial suffering? How would this benefit all beings?

Once you have set an intention that would support racial awareness and healing, have it be a focus in your mindfulness practice. The Buddha speaks of the four bases of success: (1) You must be interested; (2) You must apply effort and energy; (3) You must think about what you are trying to do, and; (4) You must look at the results or impact of what you have done.

Be curious about what arises as you inquire, and explore with an attitude of kindness and tenderness.

Form a Racial Affinity Group

No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.

—Albert Einstein

We all want to touch a deeper truth about our belonging—something greater than the stories we’ve been told or tell ourselves. Fundamentally, we all need a place where we can be safe, curious, and unedited so that we can discover the ignorance and innocence of our racial conditioning and racial character as a collective. We want to understand deeply what is difficult to acknowledge, feel, and attend to within us and among us. As a diversity consultant to organizations and sanghas, I encourage the creation of racial affinity groups and have found that there are many needs that they can address, such as supporting practitioners in healing generational traumas, attending to hurts and regrets, and fortifying people’s capacity to open and serve with less suffering.

White people need to see race and understand themselves as racial beings with roots and a collective history of power and privilege. In a racial affinity group, white people can discover together their group identity and discern its privileges and impact without the aid of and dependence on people of color. Together, whites cultivate racial solidarity and compassion for themselves and support each other in sitting with the discomfort, confusion, and numbness that often accompanies racial awakening.

While many people of color can readily relate to their group identities, they may not be as knowledgeable about or inclined to explore the diversity that exists within people of color groups. A racial affinity group supports people of color in recognizing and attending to the impact of internalized oppression without the distraction of educating white people. It also allows us to explore the presumed solidarity, invisibility, and unspoken hierarchy of suffering that exists within and among the diverse collective of people of color.

Many people say, Why don’t we all just get in a room and figure it out? But it’s not so simple; our conditioning is entrenched. When whites and people of color attempt to dialogue across race as good individuals before we have understood our racial identities as a collective, much harm is done. One myth among white people is that they can only learn about race from people of color. If no person of color is present, it appears that they do not know what to do. Yet it is precisely this territory that can be intimately explored in a White Affinity Group.

When people of color enter into dialogue with white people without having engaged in an intimate inquiry of our collective diversity, we feel more vulnerable, frustrated, isolated, and hopeless. People of color tend to carry the burden and chronic disappointment from educating whites about their resistance and denied history and its collective and institutional impact. This suffering is cumulative and has resulted in more harm than systemic change and unity. From this accumulated anguish, we become angry and convinced that we know all we need to know about white people. A habitual focus on white people can distract us from knowing ourselves as a diverse body. Exploring this territory in a POC affinity group can be a fortifying and healing refuge and an alternative to expecting white people, who often are not aware of being racial beings, to support the immediacy of our racial suffering.

Unnecessary harms are reduced with racial affinity groups because they support individuals in knowing intimately the experience of being a racial collective. Racial separation, in this sense, is not unwholesome but rather a necessary step in supporting greater literacy, skillfulness, and awareness to address racial suffering.

To form a racial affinity group, begin by bringing together three to seven people of the same race. The content explored in a racial affinity group varies and may include discussing articles or books, sharing lineage and ancestry, and deepening compassion among members. I encourage groups to make a yearlong commitment, meeting monthly for three hours, and to spend the first few gatherings practicing mindfulness together and listening to each other instead of engaging in dialogue. Here are a few questions to get started:

When did you first realize you were of the _______ race(s)?

What impact did that have on you?

What is your racial history, lineage, and inheritance?

How does it impact your life, beliefs, behavior, and consciousness?

How does it feel to be invited to consider these questions?

A racial affinity group can be a safe place to cultivate racial curiosity, awareness, literacy, and healing, and to learn about one’s own racial history, biases, diversity, and impact. They help expand racial perspectives beyond conditioning and cultivate an open and forgiving heart. Buddhist communities committed to liberation must encourage safe structures that educate its members on racial awareness and reconciliation.

Practice Compassionate Self-Reflection

Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.

—bell hooks

Maintaining our mindfulness practice is key to racial inquiry and healing. A racial affinity group will stimulate the habitual heart-mind and it will be helpful to turn inward, pause, and notice how we are meeting the rough edges of racial injury and bringing heart to it. In practice, we want to stay close to body and breath and our fleeting feeling tones, and recognize when our stories take us somewhere other than the present moment. The dharma offers many tools that can support us in facing and understanding our experiences of racial suffering, all of which should be held in an atmosphere of kindness and self-compassion. In our practice, we can notice how beliefs live, what thoughts we are giving birth to, and how we feel when thinking about them. We can acknowledge where we get stuck and what supports letting go.

In this light, I have found a practice called RAIN to be helpful. Beginning in stillness, connect with body and breath. Invite a kind and compassionate moment, memory, or entity to fill your heart and mind. Rest a moment in this recollection. Next, bring to mind your racial healing intention and allow this intention to be held in this recollection of kindness and self-compassion. When you feel you have established a baseline of inner stillness, begin the RAIN inquiry:

R – Recognize what’s happening and name it. Is there a bodily sensation of heat, tightness, pulsing? An emotion or thought of revenge, envy, fear, anger, helplessness, shame? A thought of an old story, hurt, or belief?

A – Allow the experience to be what it is without preferences, likes or dislikes. Pause here and allow a minute or so to welcome and surrender to the fullness of this experience without a story about it. Know the freshness of each moment without resistance.

I – Intimately Investigate. From inside your experience, notice the perceptions, thoughts, emotions, stories, and beliefs that are being revealed. Name the fleeting feeling tones you are experiencing: pleasant, unpleasant, neutral. All experiences are to be intimately known but not clung to. Notice when the intensity of what arises ceases. Open your awareness to include the spaces in between what arises. You can pause or even rest here.

N – Nurture. Suspend identification—I, me, mine—with the experience you are having. Explore what’s needed. What can you offer that would be nurturing and reduce suffering? Do you need to forgive? Learn something new? Let go? Recommit? Practice self-compassion? In your heart-mind, see yourself making this offer and notice how your experience changes.

Every time we weather the storm of inner racial discomfort—whether it be numbness, confusion, or aversion—we are reprogramming the hardwiring of our conditioning and allowing our hearts to simmer in the bare truth of our direct experience without turning away. Intimacy with our own racial suffering and freedom supports us in engaging others with integrity.

Stand for Racial Justice

If you are neutral on situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.

—Desmond Tutu

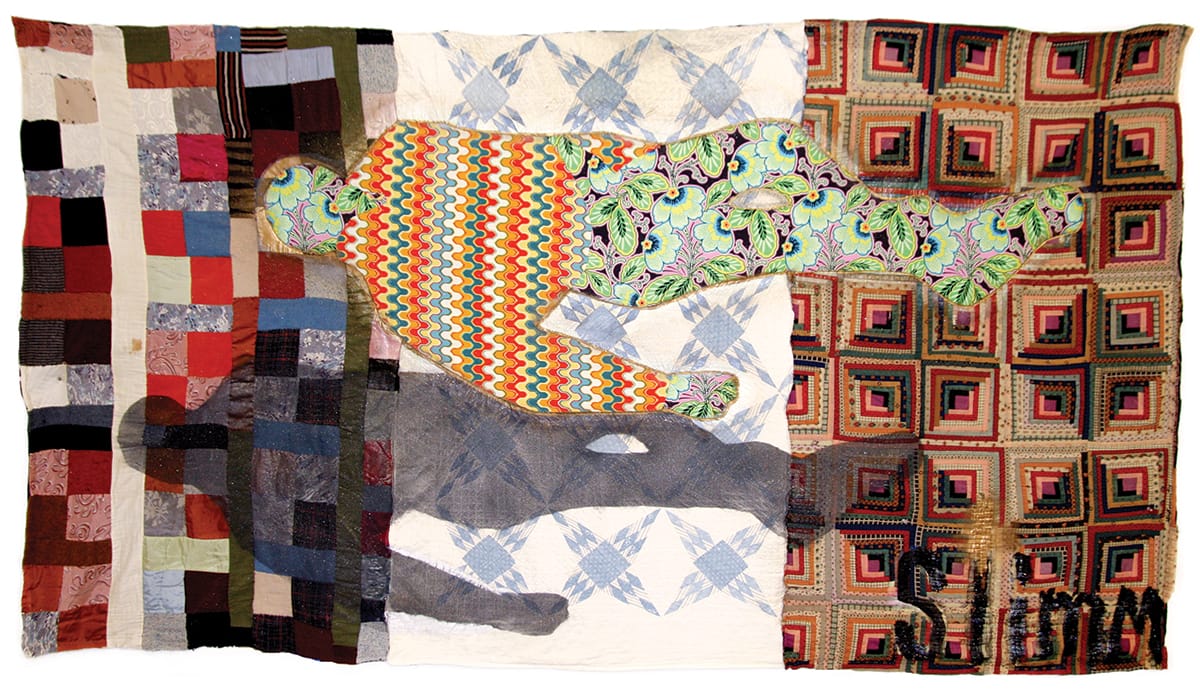

In the West, we live within a racial context of injustice, hatred, and harm. Whether subtle or openly cruel, out of innocence or ignorance, the generational and often unconscious conditioning that breeds social and systemic norms of racial dominance, subordination, and separation, nuanced in every aspect of our day-to-day lives, is tightly sewn into the fabric of society.

Don’t stand for racial justice out of guilt, anger, or revenge. Stand for racial justice because it strengthens the well-being of all humankind and calls us to embody the precepts of our practice.

A central principle of Buddhist ethics is that we practice not for ourselves but for the benefit of all; therefore, the conditioning that perpetuates racial suffering and separation is to be known and uprooted through our practice and our actions. We all have a part to play in the symphony of racial healing.

Practice Forgiveness

No matter how hard the past, you can always begin again.

—Jack Kornfield

When we commit ourselves to racial healing and human kindness, we will make mistakes. I advise practitioners to give themselves ten Get Out of Jail Free cards per day. On one side of this card, write how you blew it. On the other side, write what you learned from it.

It is a delusion to believe that our hearts won’t be broken again and again in this awakening practice, and that we won’t find ourselves often in the throes of fear, righteousness, and ill will. But we can acknowledge these contractions, forgive ourselves, and, when centered, apologize and forgive others. Resisting forgiveness causes much injury and strengthens conceit. The wise one always forgives first. The practice here is one of bravery and empathy, to not give up on any being or shut anyone out of our heart. This requires us to be both tender and wise in the face of racial suffering and to know that we can always begin again.