A sharp clack echoed through the garden, and she looked up. The timekeeper, a novice who had just taken her vows, stood on the walkway, holding her wooden mallet, getting ready to strike the wooden plaque again to signal time for zazen and evening service. Aikon could hear people arriving, taking off their shoes and heading toward the zendo.

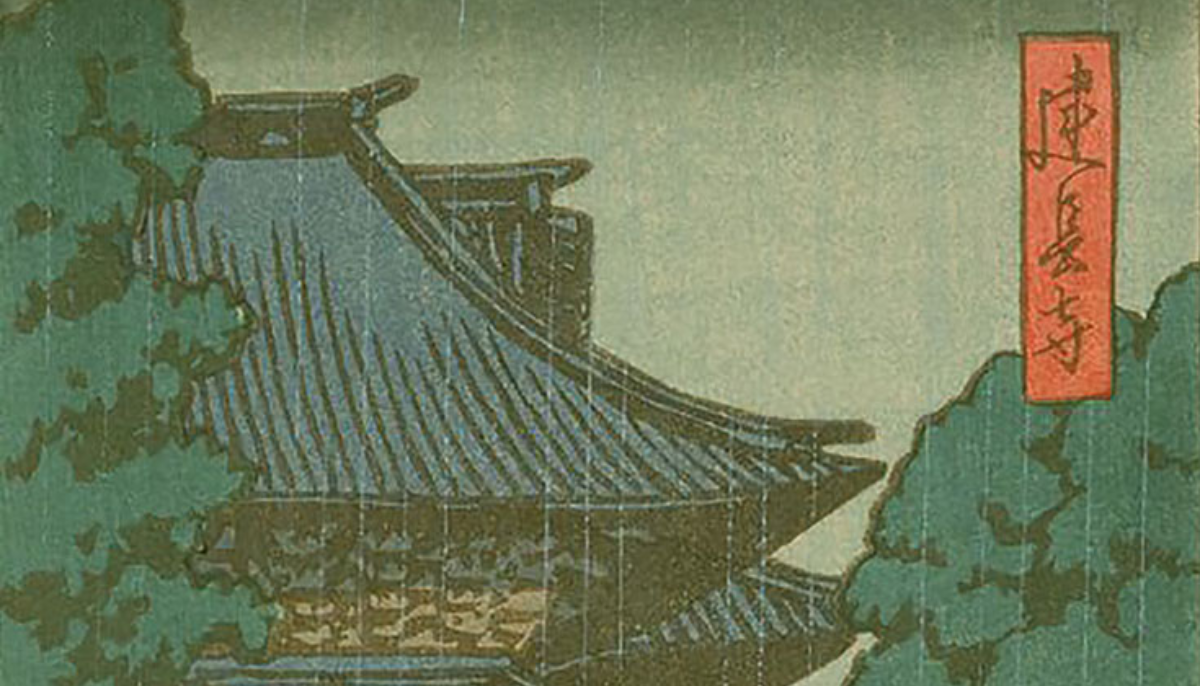

Ever since her book hit the bestseller lists in Japan, people had been showing up to the little temple. Some came once or twice out of curiosity, but others, mostly office workers from nearby companies, had started coming regularly to sit zazen, listen to her dharma talks, and attend daylong retreats. A few of the women, refugees like Aikon from the corporate world, asked to stay, to be ordained and live there as her students, so now there were three nuns in residence, too. The temple was doing well, but sadly, her teacher had not lived long enough to see this.

She closed down her computer. The rest of the emails would have to wait. She stood up slowly, stretching her legs, and then changed into a more formal robe. At the altar, she lit candles and a stick of incense. A framed portrait of her teacher rested beside the Senju Kannon. He was dressed in his finest ceremonial robe, the one she’d mended so often because he could not afford a new one. He gazed at her from the frame, and even though his mouth was stern, his eyes were smiling, as if at some private joke, one that he expected her to share. She touched the stick of incense to her forehead, but before she made the offering, she paused and looked at him, meeting his gaze and holding it—something she had never done while he was alive.

Well, she asked him silently. Are you satisfied?

She’d never known whether her teacher had believed in her or not. When, bubbling with excitement, she had told him her idea about writing a book, he’d sat there with his eyes closed, patiently listening as she explained how tidying was very trendy, and the magazine she used to work for published many lifestyle articles about clutter, and books on the subject had even become international best sellers, and when she was finally done, he just sighed. If you think your book will help a few people, you should write it, he said. She remembered how dull his eyes were then, all the brightness gone out of them, and how his head drooped like an old camellia blossom on a wilting stem. I must lie down now, he said. I’m very tired.

That was the last time he had sat upright. In the months that followed, she had watched over him, working feverishly on her book and listening to the sound of his labored breathing. She knew he didn’t have much time left, and she wanted to finish the book so that his spirit would be at peace when he died, knowing his temple was safe. Every morning, noon, and evening, she performed services in the abbot’s quarters, lighting incense at the altar, chanting sutras, and making prostrations. Sometimes while she was chanting, his lips would move. Sometimes he pressed his palms together over his heart. And all the while, the Senju Kannon watched over them. She was very beautiful, sitting on her lotus, the manifestation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, whose job it was to watch over the Realm of the Hungry Ghosts. Aikon, who had dusted each of her arms and heads, felt very close to her, and as she sat at her teacher’s side, writing late into the night, she would gaze up at Senju Kannon and think about the Hungry Ghosts, with their great, big bellies that were always empty and their insatiable appetites and never-ending desire for more.

Their mouths were as tiny as pinholes and their throats were as thin as a thread, so they could never consume enough to satisfy. Aikon understood their torment. Dear Senju Kannon, she prayed. Please help me write this book. Please let my book be of help to others who suffer like I did. Please let my book be a huge best seller so I can pay for the new roof.

On the day her teacher died, the roofers still hadn’t been paid. With a heavy heart, she sat with him and watched him as he struggled to breathe. She had failed to finish the book in time and failed to fulfill her promise to bring in income for the temple. He must be terribly disappointed in me, she thought. If he died disappointed, would he become a hungry ghost, too? It was a dreadful thought. And the old temple, what would become of it? Would the land be sold and the temple torn down to make room for office buildings and high-rise condominiums? In the last month of his life, her teacher had given her dharma transmission and made her his dharma heir, but without the temple, there was little to inherit or pass on. Would his lineage die as well?

And what would become of her? Where would she go?

It was as if her teacher could hear her thinking. He had been unresponsive for days, as his breathing slowed and the silence between each inhalation grew longer. But just then, he opened his eyes and looked straight at her, and his eyes were bright and burning with intensity. He didn’t say anything, but he didn’t need to. She knew what he was thinking.

Okay, she whispered. I won’t give up. Somehow, I’ll keep our temple going. I promise.

It seemed like he heard her. The light in his eyes seemed to flicker in response, and then he blinked and closed them forever.

Now she still felt his eyes on her from inside the portrait frame, watching her with that quizzical expression. The curl of smoke trailed from the tip of the incense as she reached forward to make the offering, planting the stick firmly in the bowl of ash.

“You thought I couldn’t do it,” she said. “But I did.” Her assistant, another novice named Kimi, slid open the door, bowed, and then stood aside to let her pass. Aikon stepped out into the hallway that led to the zendo, bowing to the timekeeper as she passed and glancing at the graceful calligraphy painted on the wooden plaque. It was an old Zen poem, written by her teacher in archaic Chinese characters:

Great is the Matter of Birth and Death.

Life is transient. Time will not wait.

Wake up! Wake up!

Do not waste a moment!

The verse, while admonitory, always made Aikon perk up and pay attention. In the zendo, she settled herself in her teacher’s old seat and looked out over the room at the rows of meditators who were settling on their cushions, turning to face the smooth, white walls. On one side were the guests and parishioners, and across from them were the nuns. She ran her eye down the row, checking her students’ posture, pleased to see that their backs were straight and their heads cleanly shorn and gleaming in the dim twilight. It was a lineage of women, Aikon thought. That’s what her teacher got. None of them were looking at her. They were sitting with their eyes downcast, deep in meditation, but if they had been watching, they would have seen a tiny smile, like a shadow, flicker across her face. Strong, competent women, the abbess thought. The old man got what he deserved.

From The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, published by Viking. © 2021 by Ruth Ozeki Lounsbury.