You’ve probably heard the Sanskrit word mandala (“circle”). It’s used it in English these days to refer to a beautiful, radially symmetric design, usually a drawing or a painting. In the case of Buddhist mandalas, the structure can be similar, with a center point and its periphery. However, in the Buddhist practice of mandala offerings, the mandala symbolizes two things: the material universe as a container with all sentient beings as its contents and the pure lands of buddhas and bodhisattvas and the deities within.

Mandala offering is an integral part of the foundation practices of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism called ngöndro. Most ngöndro texts contain nine main trainings or sections. The Outer or Common ngöndro contains the first four trainings: Contemplations on the Precious Human Birth, Impermanence, Karma, and Suffering. The Inner or Uncommon ngöndro has the last five trainings: Refuge, Bodhicitta, Mandala, and Guru Yoga. These practices aim to reduce our fascination with the endless pursuit of what we desire and the avoidance of unwanted circumstances.

The main function of mandala offering practice is the generation of positive karmic force, punya in Sanskrit, commonly translated as merit.

Mandala offerings are a central ritual practice in Tibetan Buddhism’s ngöndro, aiming to purify attachment and cultivate generosity. The practice involves visualizing offerings, reciting verses, and making physical offerings. The main function of mandala offering practice is the generation of positive karmic force, punya in Sanskrit, commonly translated as merit. The mandala offering starts with polishing a round metal surface, or mandala plate, symbolizing the clearing away of the two causes of our unawakened slumber (emotional obscurations and rigid concepts of subject, object, and action). Then, we make offerings upon that surface to the infinite manifestations of the three jewels, for the sole purpose of becoming able to benefit all sentient beings impartially as a buddha. This is further expanded by imagining the various levels of offerings filling space.

Merit = Positive Karmic Force

Merit is essential for clearing obstacles to awakening and creating the good circumstances needed for spiritual practice. According to the Mahayana view, if positive actions are done altruistically and the virtue of doing so is dedicated to all living beings, then our actions become part of the path to awakening. On the other hand, if our positive actions are tinged with transactional ideas, their positive effects (such as a higher rebirth, wealth, and access to dharma teachings) decay over time.

The goal of ngöndro practice is to clear away any obstacles to awakening our latent buddhahood. Once we have attained buddhahood, we will be of benefit to beings everywhere. However, unless you initiate ever-increasing positive momentum through constructive altruistic deeds done with pure bodhicitta, that will be impossible. The good circumstances we need to be able to practice in this and future lives require vast merit. Without merit, we will not meet with great teachers and receive the ripening empowerments and liberating instructions that we need to practice Vajrayana, Mahamudra, or Dzogchen. Even if the Buddha or Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) were to appear to us in person, we would not have the pure and positive mind necessary to see their qualities.

The formal mandala offering practice in the ngöndro provides a structure that allows us to generate merit by harnessing the benefits of making offerings while undermining subtle or overt thoughts of personal benefit and our judgmental minds.

The Holistic Technique of Making Mandala Offerings

When I say mandala offering practice can be holistic, I am addressing how it uses our body, speech, and mind in concert, to accumulate and gather merit. These mental, verbal, and physical aspects of the practice work together to efficiently foster the conditions for our awakening by using positive karmic force.

Here, in a nutshell, is how they work:

- On the mental level, we bring to mind images of everything we love and desire, mentally multiply them to infinity, and present them to our refuge sources as a gift. The sources of refuge, also referred to as the refuge field, pictured in the ngöndro, usually consist of a tree depicting key historical figures, deities, and dharma texts from the specific lineage of the practice from ancient times to the present. The refuge field can also be either a solitary figure or a male and female pair symbolizing the essence of all the qualities of the three jewels or an elaborate tree ornamented with dozens of figures. A previous section of the ngöndro practice, which focuses on the refuge practice, thoroughly familiarizes the practitioner with this visualization.

- We employ our voice to recite a beautiful offering verse. The words help us dig deep to identify everything we hold dearest and present it as an offering to the sources of refuge.

- We pair the mental offering and our vocalized offering of superabundant generosity with physical gestures of giving. We place piles of small, clean offering substances, such as grains or semi-precious stones, on a polished surface to create an imagined world of everything wonderful and let it go. It’s like building a big, beautiful sand castle at low tide, all the while happily accepting that it will be offered to the sea at high tide.

The View

The mandala offering process also reduces our personal feelings of attachment, which helps us break down dualistic thinking. While we might have a sense of the objects of refuge as being separate from ourselves, during the mandala offering process, we aim to cultivate the view that the offerer (oneself), the offering itself, and the recipients of the offering are all empty of inherent existence and are illusory. On this level, the acts of repetitive offering may awaken a visceral sense of what “emptiness” actually means.

The Practice

Your Hands as Offering Tools

Take a look at your hands and consider what they mean to you. The things that come to mind for me relate to my activities in the world: building, writing, grabbing, cooking, and gardening. Whether prompted by conscious or unconscious impulses, our hands are instruments of our mind, enacting our wishes for physical and economic survival and pleasing sensations.

While it’s obvious that gestures can be generated by our minds, it’s less obvious that things can go the other way; gestures can affect our thinking and enhance recall. Psychologists Sotaro Kita, Martha Alibali, and Mingyuan Chu, in their 2017 article in Psychological Review, “How Do Gestures Influence Thinking and Speaking?”, noted many studies where that was observed. For example, when study participants in one study practiced a route on a street map by gesturing with their hands, they remembered it better than when their hands were voluntarily restricted. In other words, we can learn new things, broaden our minds, reason better, and retain new information more easily when we pair gestures with speech. In this way, mandala offering practice uses our human drives, symbolized by our hands, as a way to support our spiritual transformation.

The Two Mandalas

Two physical mandalas, the accomplishment mandala and the offering mandala, are used in this practice, reflecting our inner visualization in physical form..

The Accomplishment Mandala

This particular mandala structure is called the “mandala, which is the support for accomplishment” or the “accomplishment mandala” for short. It is seen as the domain of the deities of your refuge tree, such as Guru Rinpoche, Yeshe Tsogyal, Vajradhara, or Troma Nakmo, according to your own practice lineage.

Setting Up the Accomplishment Mandala

To set up for this practice, a three-dimensional tiered mandala, or mandala offering set, is placed on the shrine. The mandala consists of a large pan at the base and three rings filled with saffron rice or semi-precious stones, which make up the next three layers or tiers. The piles on the mandala you create represent the main deity and their entourage. When setting up the mandala, if your refuge visualization is complex, with many figures, you then gradually fill the three layers while imagining that each handful represents the deities of your refuge tree.

A simpler version is recommended by both the Nyingma master Dudjom Rinpoche (1904-1987) and the Karma Kagyu tradition. It consists of cleaning a mandala base, on which five cone-like heaps of dry saffron rice are placed, with one in the center and four in the cardinal directions, representing the Buddhas of the five wisdoms: Vairochana, Vajrasattva-Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, and Amogasiddhi. Each of these male buddhas symbolizes a painful emotion that can be transformed into an aspect of your underlying pristine consciousness. The five heaps can also symbolize five female buddhas, representing the five elements: Dhatavishvari, Mamaki, Buddhalochana, Pandaravasini, and Samayatara.

Once the accomplishment mandala is placed on the shrine, the traditional seven to eight offering bowls containing water are placed in front of it. These offerings represent water for washing, water for bathing, flowers, incense, light, perfumed water, and food. In some traditions, there is an eighth bowl for an offering of sound.

As an alternative to this shrine setup, you may simply visualize the sources of refuge in front of you without this placeholder on your shrine.

Each Buddhist tradition and lineage has its own instructions for setting up the mandala, so always check the exact procedure of your lineage with your teacher.

The Offering Mandala

Setting Up the Offering Mandala

To prepare to offer a mandala, imagine the refuge tree in front of you and bring to mind feelings of faith and devotion toward the sources of refuge. Feel that the refuge deities are right there in front of you. Begin the practice by uniting your hands in front of your heart in the mandala mudra (Sanskrit for “gesture”) that dates to ancient India and represents the universe.

Recite the mandala offering verse in your practice text one to three times. Then, lay a towel or cloth across your lap, covering your thighs and the dip between them. Pick up a mandala offering pan (not the one on your shrine) and hold it with the open side down at your heart level in the fingers of your left hand. The smooth surface of the pan symbolizes the entire universe.

Start ceremonially cleansing the smooth surface of the offering pan while reciting the purification mantra known as the Hundred-Syllable Mantra of Vajrasattva:

OM VAJRASATTVA SAMAYA MANUPALAYA VAJRASATTVA DENOPA TISHTA DIHO ME BHAVA SUTO KAYO ME BHAVA SUPO KAYO ME BHAVA ANURAKTO ME BHAVA SARVA SIDDHI ME PRAYATSA SARVA KARMA SU TSAME TSITTAM SRIYAM KURU HUM HA HA HA HA HO BHAGAVAN SARVA TATHAGATA VAJRA MA ME MUNTSA VAJRA BHAVA MAHA SAMAYA SATTVA AH

As you recite the mantra, wipe the pan clockwise with your right wrist, polishing the surface three times. Then, think to yourself, “I am cleaning away the obscurations that are veiling my awakening.”

Some traditions suggest using a little saffron water on the pan as you make the polishing motion. If you wish to do so, just a few drops of saffron water are needed.

The Practice

As you go through these steps, bring to mind everything you love and desire that doesn’t belong to someone else, and offer it to the refuge source. Next, expand the size and quantity of your mental offering to encompass the whole world. Make it grow a billion times to fill the universe. The key point is to visualize as clearly as possible and as much as possible and offer it to the refuge deities without clinging.

This imagining is paired with physically piling your offering with the right hand onto the round surface of the mandala pan, supported by the left. Typically, grains or semi-precious stones are piled in an ordered pattern, representing an ancient Indian schematic of the world. The offering verse is simultaneously recited, and the mental offerings are visualized.

After each round of offering is complete, tilt your mandala pan inward and drop the grains or stones into your catch cloth below. Wipe the mandala pan with your wrist, and begin the offering sequence once again by immediately placing your piles again while reciting the verse.

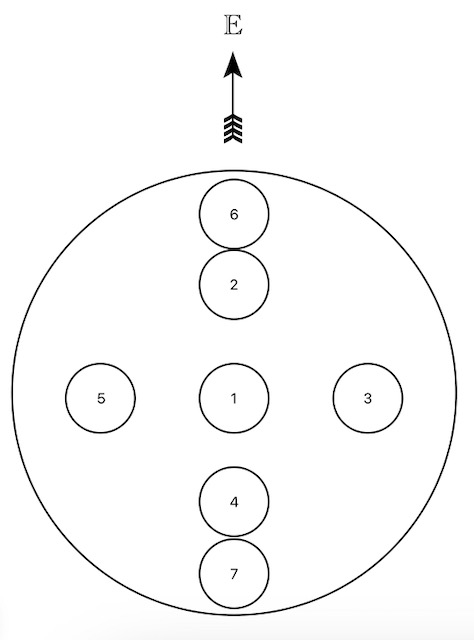

Take a look at the following diagram. Holding the pan flat in front of you, its surface has directionality. In Dudjom Rinpoche’s tradition, for example, the point farthest from you is designated as east. South is right, west faces you, north is to your left. Other traditions may reverse east and west. The order and placement of the piles are as follows:

- Center: Mount Meru

- East: Purvavideha

- South: Jambudvipa

- West: Aparagodaniya

- North: Uttarakuru

- East: Sun

- West: Moon

Following all the steps of the mandala offering practice might feel impossible the first time. But that’s kind of the point! Your distraction is eliminated by keeping your body, speech, and mind busy. It is distracting you from being distracted.

The Traditional Offerings

In the standard ngöndro guidebooks, specific traditional offerings from medieval India are visualized. These include the “outer offering,” “the inner offering,” and the “secret offering.”

The Outer Offering

Vajrayana Buddhists believe that the experiential “world” of sentient beings in samsara was perceived by the Buddha, with his divine eye, as a three-dimensional schematic of a flat disc with a tall central mountain (called Mount Sumeru), an ocean with four continents in the cardinal directions, and two subcontinents between each of them, surrounded by a ring of mountains and filled with sentient beings. There is a sun and moon and various heavens of gods higher up and hells below.

Then, you multiply that visualization. One thousand worlds is called a first-order universe. One thousand first-order universes is a second-order universe. One thousand second-order universes is a trichiliocosm. This is the traditional calculation of how big Buddha Shakyamuni’s field of activity is!

Wealth

As you mentally offer everything you own to others, you can examine how wealth is traditionally portrayed. Offer every conceivable quality of abundance.

Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, in his Commentary on the Dudjom Tersar Ngöndro, lists “mountains of jewels, wish-fulfilling trees, wish-fulfilling cattle, unplanted grains, treasure vases, sixteen offering goddesses who offer the five desirable qualities (form, smell, sounds, tastes, and touch).” In addition, traditional emblems are offered. These are known as the Eight Auspicious Emblems: Umbrellas, Golden Fishes, Treasure Vases, Lotuses, White Conch Shells, Endless Knots, Banners of Victory, Dharma Wheels.

Next, the Seven Precious Aspects of Universal Benevolent Monarchy are offered: A Thousand-spoked Wheel, Eight-sided Sapphire Jewel, A Sublime Queen, A Minister, The Most Powerful and Fearless Elephant, A Miraculous Horse, and Generals.

In my own practice, I have found ways to make these relatable to the modern world. For example, the elephant that carries the universal monarch around the world might be replaced with an airplane.

Offer every quality of abundance to the refuge sources, knowing that they neither desire nor need it. This process is for you.

The Inner Offering

The inner offerings are what make up your personhood: your body, the sensations you experience, your perceptions, your mental imprints and conditioning, and your consciousness. You offer all the merit you have accumulated, are accumulating, and will accumulate in the future.

You can reflect on offering each part of your body laid out directionally, like the five directions in the mandala plate. Instead of offering Sumeru, etc., offer the trunk of your body as the central mountain, your arms and legs as the four continents, and your eyes as the sun and moon.

This inner offering also includes your capacities to experience the world: your eyes and what you see, your ears and what you hear, your nose and what you smell, your tongue and what you taste, your touch senses and what you experience through touch, your mind and the objects of your thought. Anything you can imagine, anything you can think of, you can offer. Everything that pops into your head can be offered.

What about the many bodies your consciousness might have occupied in the past? Offer them, too! How about the next body and all the other future bodies? Give it all wholeheartedly, along with all their future possessions.

The Secret Offering

After the outer and inner offerings, we come to the next level of offerings. In the Nyingma tradition, your future realization and visionary capacities are also offered in advance. We don’t cling to and hoard these for ourselves; instead, we offer them.

Accumulation

If you commit to the ngöndro process, you will offer a mandala 100,000 times. Traditionally, you are instructed to add ten percent more in case there are lapses in your wording, attitude, or count.

Counting Repetitions

Here is how each repetition is counted: while you recite the verse, you make seven piles on the pan, releasing the grains or stones from the bottom of your right fist onto the designated spot for each. When the seven are complete, it is counted as one offering. Then, wipe the pan with your right wrist. The grains or stones fall into your lap cloth. Grains that fall outside the cloth should be discarded. Stones that fall outside can be washed and reused. Next, you then scoop up a fistful with your right hand and do it again.

Merging the Traditional with the Contemporary

When I started doing this practice in-depth for the first time in the 1990s, I thought it was ridiculous. So complicated and archaic! For me, managing the pan, the piles, and the mental lists felt like trying to meditate in a New York City train station during rush hour. Nonetheless, I started doing it simply because it was one of the assignments my lama gave us.

I still remember offering my past-life children, my spouse, my mint chocolate chip ice cream, mountains, and oceans. I offered planets and stars, forests and bonfires, volcanoes, and aurora borealis displays. I offered plates of delicious snacks and trays of candles. I offered all the cups of chai in India and all the Frappuccinos in Starbucks. I offered everything in my usual present life, and I was very happy to replenish my supply of offerings with the traditional visualization list.

Sitting there on my bedroom floor, grains of saffron rice scattered everywhere, I noticed a shift in my mind. All my usual thoughts were gone. That made me feel relieved, as though I had been gifted a sense of internal freedom. It became easy and uncomplicated once I got accustomed to it. Offering everything I enjoyed by using my imagination undermined that perpetual feeling of want. That takes us back to the Buddha’s original insight, doesn’t it? All our suffering comes fundamentally from desire. Once we give all the good stuff away, it’s… freeing. What else is there to think on and on about? By uniting gestures of giving, the voicing of offering up everything in the universe, and the mandala practice visualization, one is transformed into a powerful force for good.

This article is adapted from Yuddron Wangmo’s book Clearing the Way to Awakening: A Nine-Step Practice from Tibetan Buddhism.