One of the most distinctive teachings of the Thai Forest Tradition is its insistence that the three parts of Buddhist training—virtue, concentration, and discernment—are intimately interconnected and have to be developed together. What this means in practical terms is, (1) you don’t have to wait for your virtue to be perfect before practicing concentration, or for your concentration to be fully mastered before developing discernment. All three have to inform one another continually for any of them to grow in the right direction. (2) When you’re practicing the higher levels of concentration and discernment, you haven’t outgrown the need to stick with the precepts. The higher levels of the path need continual grounding in virtue in order to maintain their integrity.

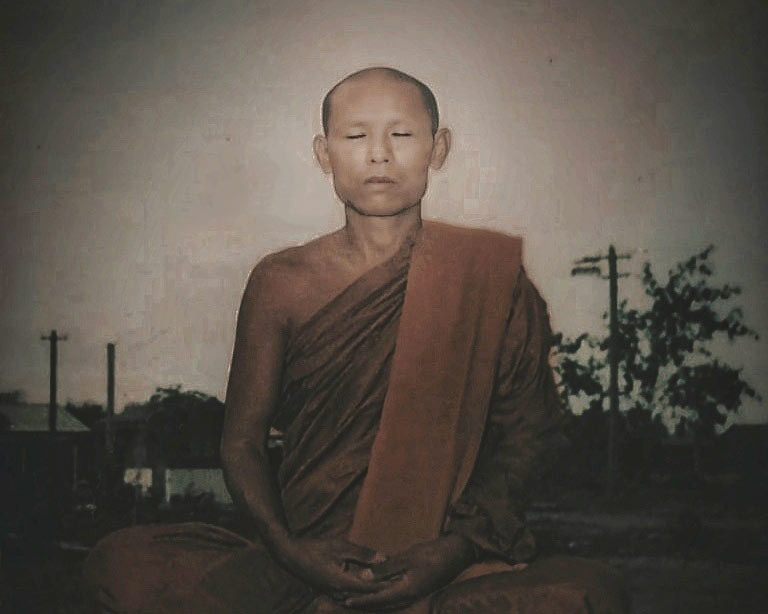

Ajaan Lee, writing in The Path to Peace and Freedom for the Mind—the book from which the following passage is taken—applies this principle to the noble eightfold path as a whole. His discussion of right mindfulness, for instance, shades into right concentration. His discussion of concentration shows that the ability to overcome the hindrances to concentration is simply a more refined application of the precepts of right speech and right action.

The same principle is at work in the following passage, where Ajaan Lee’s discussion of right action shades into right livelihood. The way he discusses these topics makes two implicit points. First, the precepts of right action aren’t just a matter of what you do in the privacy of your personal relationships. They should also inform your life in the workplace and your engagement with society at large. This is to counteract a common attitude in Thailand—and in the West as well—that if you want to stick to the precepts, you should stay out of the rough-and-tumble of government and business circles and go live in a monastery instead. Second, right action and right livelihood aren’t just a matter of avoiding unskillful actions. Based on the practice of generosity, they also have a positive role to play in furthering the good of society as a whole. In other words, they’re not just an issue of exercising restraint in your actions. They also entail making a positive contribution to the world at large.

—Thanissaro Bhikkhu

IV. Right Action: being upright in our activities. With reference to our personal actions, this means adhering to the three principles of virtuous conduct —

1. Not killing, harming or harassing other people or living beings.

2. Not stealing, concealing, embezzling, or misappropriating the belongings of other people.

3. Not engaging in immoral or illicit sex with the children or spouses of other people.

With reference to our work in general, Right Action means this: Some of our undertakings are achieved through our physical activity. Before engaging in them, we should first evaluate them to see just how beneficial they will be to ourselves and others, and to see whether or not they are clean and pure. If we see that they will cause suffering or harm, we should refrain from them and choose only those activities that will lead to ease, convenience, and comfort for ourselves and others.

“Action,” here, includes every physical action we take: sitting, standing, walking, and lying down; the use of every part of the body, e.g., grasping or taking with our hands; as well as the use of our senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and feeling. All of this counts as physical activity or action.

External action can be divided into five sorts:

Government: undertaking responsibility to aid and assist the citizens of the nation in ways that are honest and fair; giving them protection so that they can all live in happiness and security. For example: (a) protecting their lives and property so that they may live in safety and freedom; (b) giving them aid, e.g., making grants of movable or immovable property; giving support so that they can improve their financial standing, their knowledge, and their conduct, establishing standards that will lead the country as a whole to prosperity—”A civilized people living in a civilized land”—under the rule of justice, termed dhammadhipateyya, making the Dhamma sovereign.

Agriculture: putting the land to use, e.g., growing crops, running farms and orchards so as to gain wealth and prosperity from what is termed the wealth in the soil.

Industry: extracting and transforming the resources that come from the earth but in their natural state can’t give their full measure of ease and convenience, and thus need to be transformed: e.g., making rice into flour or sweets; turning fruits or tubers into liquid—for instance, making orange juice; making solids into liquids—e.g., smelting ore; or liquids into solids. All of these activities have to be conducted in honesty and fairness to qualify as Right Action.

Commerce: the buying, selling, and trading of various objects for the convenience of those who desire them, as a way of exchanging ease, convenience, and comfort with one another—on high and low levels, involving high- and low-quality goods, between people of high, low, and middling intelligence. This should be conducted in honesty and fairness so that all receive their share of justice and convenience .

Labor: working for hire, searching for wealth in line with the level of our abilities, whether low, middling, or high. Our work should be up to the proper standards and worthy—in all honesty and fairness—of the wages we receive.

In short, Right Action means:

being clean and honest, faithful to our duties at all times;

improving the objects with which we deal so that they can become clean and honest, too. Clean things—whether many or few—are always good by their very nature. Other people may or may not know, but we can’t help knowing each and every time.

Thus, before we engage in any action so as to make it upright and honest, we first have to examine and weigh things carefully, being thoroughly circumspect in using our judgment and intelligence. Only then can our actions be in line with right moral principles.