Sharon Salzberg knows suffering. At age nine, she was dressed in her Halloween ballerina costume, watching Nat King Cole on television, when something went horribly wrong. Her mother started bleeding violently and was whisked away amid the panic of flashing ambulance lights. That was the last time Salzberg saw her mother, who died two weeks later.

Salzberg was sent to live with her grandparents, and when she was eleven her estranged father appeared—a troubled, dishevelled stranger who told her, “You have to be tough to survive life.” Six weeks later, he overdosed on sleeping pills, and for the second time, Salzberg watched her parent being rushed away by ambulance. Her father was never to function outside of the mental health system again.

The adults in her life never talked about loss or grief, and Salzberg learned that silence meant safety. Little did Salzberg know that someday, plunging into the heart of her suffering would be her greatest teacher—and make her the renowned Buddhist teacher she is today.

“There was no affirmation from the external world about what I was experiencing inside. I felt frozen and unhappy,” says Salzberg. “I think that’s always the case when children are kept from the truth, however hard the truth is to bear.”

Salzberg writes in her bestselling book Faith that she felt like she lived a separate, shadowed existence from the rest of the world: “Feeling so different, I liked playing it safe more than anything, seeing life from a distance; never really engaging.”

Even though it was hard, I thought “There’s truth here. This is it.”

But something within her knew there was more: “There was some voice inside that was very positive,” she remembers. “I was waiting, because I thought there was something, something good, out there.”

When I ask her where that sense of possibility came from, Salzberg shrugs. “That is beyond me,” she laughs.

In college, Salzberg took an Asian studies class, where for the first time she heard the Buddha’s first noble truth—because we are born, we experience suffering. Something within her came alive. “I knew it to be true. The circumstances of my own life proclaimed it,” she writes. “It was like, ‘Right! This could be it!’ ”

Though she’d never travelled farther than Florida, Sharon Salzberg decided to go to India to study meditation. “The methods were not available in the West in the way they are now,” she explains. “If you actually wanted to practice, one way or another you stepped out of conventional reality.”

A few days before her departure, she went to a talk by the famed Tibetan master Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. When Salzberg asked him for recommendations about what she should do in India, Trungpa Rinpoche replied, “In this matter, you had best follow the pretence of accident.”

Salzberg had no idea what he meant. It was the first sign that this would be a journey beyond anything she had ever experienced.

Arriving in India was scary. Salzberg writes that she had “never seen life displayed so openly before, with joy and suffering all jumbled together. Nothing seemed hidden, and there was nowhere for me to hide.” However, her quest to find a teacher proved fruitless until she heard Daniel Goleman, later the bestselling author of Emotional Intelligence, mention a meditation retreat in Bodhgaya.

When Salzberg arrived there, she sought out the bodhi tree where the Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment. There she encountered an elderly Tibetan monk who offered her a seed from the bodhi tree to eat. His name was Khunu Rinpoche, and he was one of the Dalai Lama’s teachers. Sitting by him, Salzberg began to feel the possibility of defining herself by something other than her family’s painful struggles, of “knowing, even in the midst of great suffering, that we can still belong to life, that we’re not cast out and alone.”

The ten-day retreat was led by S.N. Goenka, a former Indian businessman and famed teacher of vipassana (insight) meditation. He told the participants that the point of the practice was to see, and free themselves from, old patterns. Salzberg was surprised at the emotions that began to surface.

“Did I know I felt afraid? Or angry? Probably not, until I went to India, and then I was like whoahhh!” she remembers. “Even though it was hard, from the moment I started, I thought, ‘There’s truth here. This is it.’ There was a deep sense of rightness.”

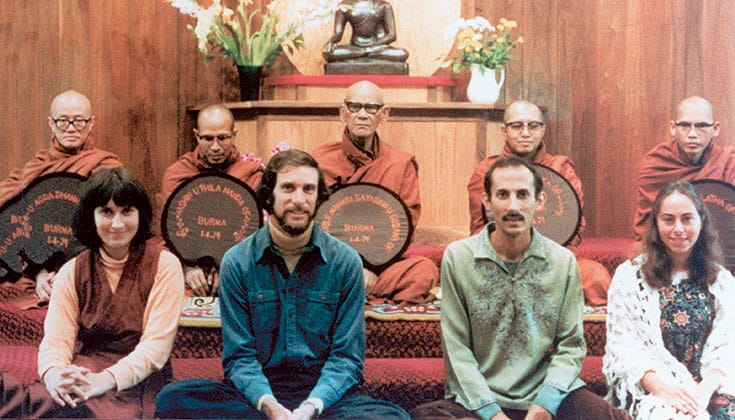

Salzberg found a sense of community among her fellow seekers. That famed Goenka course included many Westerners who would become leading figures in the growth of Eastern spirituality in the West, including Ram Dass, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Mirabai Bush, Krishna Das, Dan Goleman, and, of course, Salzberg herself.

“Many of my close friends are still people I met at my first retreat in January of 1971,” she says. “When I say all beings want to be happy, what I actually think I mean is we all want some sense of belonging.”

Putting her faith in a tradition and a body of knowledge gave Salzberg a sense of confidence. “I took refuge in the Buddha very happily,” she says. “There was an authenticity or integrity to what you were learning. There was a sense that you’re not alone—there’s wisdom here, people have done this, they have walked this path.”

On the final day of the retreat, Goenka introduced the practice of metta, or loving-kindness. “I had never been so at home, never been so happy,” Salzberg says. “This is what I had longed for, not surprisingly—a sense of unconditional love.”

She experienced another kind of love when she met Dipa Ma, another Indian-born teacher in the Burmese meditation tradition. Dipa Ma would set the course for Salzberg’s adult life. “She was an incredible model, someone who had suffered so much personally, far more than I, and had emerged with such huge compassion and strength.”

With Dipa Ma, Salzberg felt the maternal love she had been craving since her mother’s death. “An incredible love would come forth from her. It was restorative. It was incredibly healing.” Salzberg says good teachers become like good parents and can help students re-parent themselves. “What’s that saying? It’s never too late to have a happy childhood?”

In 1974, Salzberg went to say good-bye to Dipa Ma because she was going back to the U.S. for what she thought would be a brief visit. Joseph Goldstein was already teaching meditation at Naropa Institute in Colorado, and Dipa Ma told Salzberg, “When you go back to the States, you’ll be teaching with Joseph.” Salzberg said, ‘No, I won’t,” and Dipa Ma replied, “Yes, you will. You really understand suffering. That’s why you should teach.”

Salzberg says this was the first time in her life she thought her suffering could be of value. “It’s very, very hard to look at pain. For her to say that to me really meant something.”

Salzberg was twenty-one years old when she returned to the U.S after four years in India. There she joined some fellow meditators from the Goenka retreat who were teaching at Naropa, creating an informal community that would produce some of the most recognizable and influential names in American Buddhism.

When she began teaching, Salzberg was terrified of public speaking and made Goldstein speak for her. “All these women were going up to Joseph and yelling at him, saying, ‘Why won’t you let Sharon give a talk? Why won’t you let her have a voice?’ ” Salzberg laughs. “He’d say, ‘I’d be so happy if she’d give a talk!’ ”

Salzberg says she took refuge from her fear in a kind of dogmatism. “I would quote things from the teachings as though they were my personal direct knowledge, rather than just saying, ‘This is my understanding of what the Buddha said.’ I had to take a big journey in terms of teaching.” It was only when she decided to talk about metta that she began to find her true voice as a teacher.

Salzberg and her friends began teaching and leading meditation retreats all over the country, sleeping on couches or floors. Then someone said, “Why don’t you start a retreat center? It would be a place where the energy of people practicing together doesn’t dissipate at the end of the retreat.” So Sharon Salzberg, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, and Jacqueline Mandell-Schwartz founded the Insight Meditation Society, one of the most important institutions in Western Buddhism.

They found a former Catholic novitiate on eighty acres of land in Barre, Massachusetts, that was for sale. The $150,000 price tag was steep, but with donations, personal loans, and a $50,000 mortgage from the owner, they were able to buy it.

When I ask if she had faith their efforts would work, Salzberg laughs. “No, not at all. Our mantra actually the first year was, ‘We can always close in a year.’ But it worked. It worked so amazingly.”

The Insight Meditation Society (IMS) was established on Feb. 14, 1976—St. Valentine’s Day. There was no model for what they were doing. “It was the first time there was a center, as far as I know, that was founded and run by Westerners without that singular Asian figure either here or back in Asia,” Salzberg says.

It was a time of excitement—and debate. Even the word “metta,” which adorns the doorway at IMS, was a source of controversy. Some people thought they should use an English word, like loving-kindness. “In the end, it just stayed,” says Salzberg, and today metta is a recognized term in the Western spiritual vocabulary.

What surprised its founders was the hunger for community they found in those who came to practice at IMS. “Community was something we took for granted, because we had had it. I know I didn’t stop to think about what it was like to be meditating in the morning and then selling insurance or something the rest of the day, where you felt like nobody shared your values,” says Salzberg. “It took a while to realize that people felt really alone in this society.”

There was no programming scheduled for the first month of IMS’s existence, so Salzberg decided to immerse herself in metta practice, something she had only done before as a ceremonial ending to retreats.

“I did metta practice for an entire week and just kept repeating these phrases, and I felt absolutely nothing,” she says. “Then one day, I dropped this big glass jar and it shattered and stuff went everywhere. I noticed that the first thought that came up in my mind was, ‘You are really a klutz. But I love you.’ I thought, ‘Look at that!’ Something was happening.”

Salzberg says this is a lesson she’s witnessed over and over again: “People expect a rush of feeling, like a breakthrough—‘I finally loved myself,” or ‘I finally forgave that jerk.’ First of all, I don’t think things are final, and, more often, it’s a gradual but very, very deep process. Very profound changes happen within you, but they are much subtler.”

Metta and mindfulness became the main focuses of Salzberg’s teaching and practice. “I thought of metta as unconditional love. I had learned the word ‘loving-kindness’ as the standard translation of metta, but when I’m teaching now I usually say ‘connection’—a profound sense of connection. It’s knowing somebody counts, that everybody wants to be happy, and that our lives have something to do with one another.”

As IMS’s reputation flourished, so did Salzberg’s reputation as a teacher. Her own growth was kick-started once again by Burmese teacher Sayadaw U Pandita in the late 1980s. By this time, Salzberg had been meditating for almost two decades. She felt free from much of her childhood grief, had come to know her own suffering and that of others, and thought she knew the power of love and compassion.

But during a retreat in Australia, Salzberg felt something shift, and the traumatic memory of her mother’s death arose. She fell into despair and panic and went to talk to U Pandita about it. He simply told her to be “mindful of the pain.” Though she tried, she knew she was still recoiling from facing her suffering head-on. One night, under a starry sky, Salzberg once again thought of her beloved Dipa Ma, and how she had found faith and love even in anguish. “I thought that if such extreme suffering could serve as the proximate cause of faith, then the suffering of my own despair must also contain a crack of light,” she writes.

Under U Pandita’s skillful direction, Salzberg began to see this chapter of her practice as a process through pain, one that could expose her vulnerability on a deeper level.

“I think Dipa Ma was right. It’s good for a teacher, certainly a Western teacher, to have been through a lot, because you really understand a lot of things,” Salzberg says. She saw that her suffering could serve as a connection to others, and she began recover a sense of purpose, working to free her mind for the sake of all beings.

Today, Sharon Salzberg is an established speaker, an author of many bestselling books, and one of the foremost Buddhist figures in North America. She says those attracted to her teachings often feel a connection to her knowledge of suffering.

“People say to me, ‘I want to discover my heart,’ or ‘I don’t think I have a heart,’ or ‘I hate myself,’ or ‘I’m carrying this burden of this person who’s hurt me.’ ” Salzberg recognizes herself in these students: “I used to tell myself, ‘This is wrong. This is bad. No one else feels this.’ ”

Knowing our suffering intimately is essential to freeing ourselves from it, says Salzberg. She says we should regard what we find without judgement, without holding on to or pushing away any experience and without blaming ourselves for it. “What arises in one’s mind is not something we can control. We can change the ground, to some extent, out of which emotions tend to arise, but we can’t stop things from coming up. Every moment is conditions coming together and coming apart. How we relate to what arises in one’s mind is what’s most important.”

Salzberg says that through meditation practice we can learn to regard suffering as a way to see more deeply, to get to know ourselves better, and to discern what really makes us happy. “Why suffer unnecessarily,” she asks, “if it’s distorted thinking that’s bringing forth that feeling?” In becoming more aware of our suffering, she explains, we also discover that there is always an intact place within us, an open space of awareness that can bear anything without becoming damaged. We realize that we needn’t be paralyzed by suffering.

However, Salzberg also recognizes that sometimes withdrawing may be the only option: “It’s probably smart in a lot of circumstances. For me, it was adaptive under the circumstances, for that time with the tools that I had at my disposal.”

Instead of giving ourselves a hard time for what we’re “not feeling,” Salzberg says numbness needs close attention: “For a long time I thought I needed to experience depth. So when something came up that felt kind of superficial, I would try to punch my way through, like, ‘What’s under here?’

“Then I realized that what I was practicing was dissatisfaction. I didn’t like what was there, so I thought there must be something different underneath. I learned that the practice of mindfulness is furthered most by frequency, by more moments of mindfulness in a row, even if what you’re mindful of feels or seems superficial. So rather than practicing dissatisfaction, I could work to have more moments of mindfulness in a row.”

In addition to awareness, faith in ourselves and our true capacities leads to freedom from suffering, says Salzberg. “Lack of faith in our potential limits our sense of possibility to habitual concepts. It keeps us from sensing who we might yet become.” No matter what stories we believe about ourselves, Salzberg writes, beneath them lies our own buddhanature: “Love and awareness we can place our hearts upon is present regardless of our particular conditioning or background or trauma or fears. It is not destroyed, no matter what we have gone through or what we will go through. Although some people are completely out of touch with that capacity—they can’t find it, or don’t trust it—it is always there.”

Salzberg notes the value of a spiritual friend, a kalyanamitta, to point out blind spots or to regulate emotions that overwhelm us. “People don’t tend to practice meditation these days in the old-fashioned way, with a teacher who really knows you, who can balance you and say, ‘Maybe you’re trying too hard and you’re way too judgmental’ or ‘Maybe you’re really withdrawn and you’re not engaged.’ ”

“It’s not easy to face pain,” she acknowledges. “We utilize all kinds of things, including dharma, in the service of not facing pain. It’s a fantastic thing if you have a therapist, or a teacher, or a person you know who’s going to help you not avoid it.”

And Salzberg reminds us to have a sense of humour about it all: “Instead of being freaked out and shamed and horrified at things that come up in our minds, it helps to see that they are kind of funny. I think it evokes right relationship in many ways, because there’s a sense of spaciousness.”

“We can emerge from whatever suffering we encounter, not broken and embittered, but with an ever-replenishing wellspring of unwavering faith,” Salzberg writes. If anyone knows the truth of these words, it’s Sharon Salzberg, for facing her own deep suffering that has been the key to her life of connection, community, and self-compassion—and to teachings that have helped many people face and learn from their own suffering as well.