There are two ways of seeing, and they perceive different types of objects. For simplicity’s sake, let’s call these sensory seeing and conceptual seeing. Sensory seeing perceives things that appear to our senses, and conceptual seeing perceives things that appear to the mind’s eye.

Here’s an example. You go into a restaurant for dinner and sit at a table by yourself. Instead of taking out your phone or a book, you look around at the other customers. You might see an old couple with their granddaughter sitting in a booth, a good-looking young man at a far table, and three expensively dressed women dining together near you.

Sensory seeing takes in the colors and textures of the environment—the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and so on. All the rest of your experience is conceptual. You don’t see “grandparents” and “grandchildren,” only the visible forms of three people. “Good looking” and “expensively dressed” are not visible to the eye; they appear only to the thinking mind.

Sometimes we are completely engrossed in the conceptual realm and notice nothing of the sensory environment. At other times, we are thought-free and fully absorbed in sensory experience. Mostly the two are blended together and we are unclear about what we are actually experiencing. We don’t distinguish sensory objects from the things we think about, and this obscures our experience of the richness and natural beauty of the sensory world.

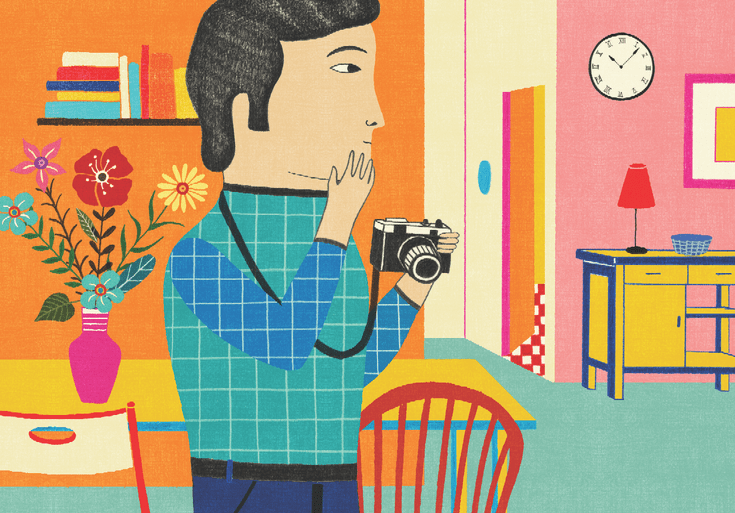

Contemplative photography trains you to see the world in fresh ways by distinguishing the sensory from the conceptual. It is a practice that brings out your natural ability to see clearly. It is also trains you to express what you see photographically. Both clear seeing and artistic communication are tremendously enriching.

The practice of contemplative photography makes use of the camera’s sensory-like abilities to help you tune into and communicate the beauty of the sensory world. Unlike living beings, cameras have only one way of seeing: they only make images of visible forms. They are blind to conceptuality. Therefore, you can use the camera to distinguish the two ways of seeing. It reveals when you are seeing clearly and when you are trying to make an image of your concepts.

The practice of contemplative photography can be divided into three steps:

1. Recognize Flashes of Perception

There are natural gaps in the flow of conceptuality. We call these moments “flashes of perception.” At these moments, sensory seeing is dominant and sensory experience just naturally shines through.

Flashes of perception are simple, vivid, and direct experiences. They are moments of clear seeing (or hearing, smelling, tasting, or touching). Learning to recognize and appreciate these moments of sense perception is the first step in practicing contemplative photography, as flashes of perception become the basis for making images.

You can’t fabricate flashes of perception because fabrication is the activity of conceptuality. But you need to make yourself available to these experiences when they naturally arise. You might have to let your mind settle a bit, but you don’t need to suppress anything that is arising in your mind. Let thoughts and feelings come and go, and look at the world in a relaxed way.

Here’s what recognizing a flash might be like. You’re in the kitchen, and your partner is doing the dishes while you put away the leftovers. Suddenly, you see sunlight from the side window illuminating a bright pattern on your partner’s back. You notice the colorful fabric of your partner’s fleece.

2. Discern the Qualities of the Perception

To communicate what you see powerfully and accurately, you need to be able to rest with the perception and not get diverted into conceptuality. Visual discernment, the second step in the practice of contemplative photography, is how you stay in the sensory mode by resting with the perception in an inquisitive way, without clinging to what you see.

Having seen the surprising richness of the light and the fabric, you might get excited by that discovery and start thinking about the fabulous picture you are going to take. Then suddenly you are back in the conceptual realm. Now’s the time to practice discernment.

Let go of the excitement and look further to determine the qualities of the perception. You might ask yourself, how much of your partner was included in the perception? Was their head included? How about the counter? Knowing the dimensions of the perception will help you determine the framing that will communicate exactly what you’ve seen.

Although it’s called discernment, this step is not particularly intellectual. It’s not a technical photographic analysis. You are not figuring anything out or evaluating things emotionally, nor are you reaching for your camera to capture anything. You are looking further at the perception to clarify what you see.

3. Form the Equivalent of the Perception

The third part of the practice of contemplative photography is called “forming the equivalent,” a term that comes from the great photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

A photograph and a perception are obviously different things, but your aim is to produce an image that is just the equivalent of what you see. You are not trying to make the photograph more interesting, more dramatic, or more anything.

You’ve experienced a rich flash of perception of light and color, and you’ve discerned what is included in the perception and what is not. Now you make an image that replicates what you have seen. You don’t need to add anything to the perception to make the photograph good, because the perception already embodies the richness and beauty of your experience. When you faithfully form the equivalent of your perception, the image will be able to convey this richness and beauty.