What is Vipassana?

Vipassana, or insight meditation, is the practice of continued close attention to sensation, through which one ultimately sees the true nature of existence. It is believed to be the form of meditation practice taught by the Buddha himself, and although the specific form of the practice may vary, it is the basis of all traditions of Buddhist meditation.

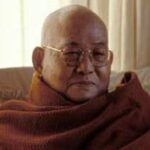

Vipassana is the predominant Buddhist meditation practice in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there was an important revival of this early form of meditation practice led by the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Burma. Following Mahasi Sayadaw’s death in 1982, Sayadaw U Pandita was chosen as his principle preceptor. U Pandita was one of the world’s leading teachers of Vipassana meditation and was been an important influence on many Vipassana teachers in the West, including Sharon Salzberg and Joseph Goldstein of the Insight Meditation Society. He was the founder and abbot of Panditarama Meditation Centre in Yangon, Myanmar.

Where & How to Sit

1. Which place is best for meditation?

The Buddha suggested that either a forest place under a tree or any other very quiet place is best for meditation.

2. How should the meditator sit?

He said the meditator should sit quietly and peacefully with legs crossed.

3. How should those with back troubles sit?

If sitting with crossed legs proves to be too difficult, other sitting postures may be used. For those with back trouble, a chair is quite acceptable. In any case, sit with your back erect, at a right angle to the ground, but not too stiff.

4. Why should you sit straight?

The reason for sitting straight is not difficult to see. An arched or crooked back will soon bring pain. Furthermore, the physical effort to remain upright without additional support energizes the meditation practice.

5. Why is it important to choose a position?

To achieve peace of mind, we must make sure our body is at peace. So it’s important to choose a position that will be comfortable for a long period of time.

The Breath During Meditation

6. After sitting down, what should you do?

Close your eyes. Then place your attention at the belly, at the abdomen. Breathe normally—not forcing your breathing—neither slowing it down nor hastening it. Just a natural breath.

7. What will you become aware of as you breathe in and breathe out?

You will become aware of certain sensations as you breathe in and the abdomen rises, and as you breathe out and the abdomen falls.

Developing Attention

8. How should you sharpen your aim?

Sharpen your aim by making sure that the mind is attentive to the entirety of each process. Be aware from the very beginning of all sensations involved in the rising. Maintain a steady attention through the middle and the end of the rising. Then be aware of the sensations of the falling movement of the abdomen from the beginning, through the middle, and to the very end of the falling.

Although we describe the rising and falling as having a beginning, middle and end, this is only in order to show that your awareness should be continuous and thorough. We don’t intend you to break these processes into three segments. You should try to be aware of each of these movements from beginning to end as one complete process, as a whole. Do not peer at the sensations with an over-focused mind, specifically looking to discover how the abdominal movement begins or ends.

9. Why is it important in this meditation to have both effort and precise aim?

It is very important to have both effort and precise aim so that the mind meets the sensation directly and powerfully.

10. What is one way to aid precision and accuracy?

One helpful aid to precision and accuracy is to make a soft, mental note of the object of awareness, naming the sensation by saying the word gently and silently in the mind, like “rising, rising . . .,” and “falling, falling. . .”

11. When the mind wanders off, what should you do?

Watch the mind! Be aware that you are thinking.

12. How can you clarify your awareness of thinking?

Note the thought silently with the verbal label “thinking,” and come back to the rising and falling.

13. Is it possible to remain perfectly focused on the rising and falling of the abdomen all the time?

Despite making an effort to do so, no one can remain perfectly focused on the rising and falling of the abdomen forever. Other objects inevitably arise and become predominant. Thus, the sphere of meditation encompasses all of our experiences: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, sensations in the body, and mental objects such as visions in the imagination or emotions. When any of these objects arises you should focus direct awareness on it, and silently use a gentle verbal label.

During Practice

14. If another object impinges on the awareness and draws it away from the rising and falling, what should you do?

During sitting meditation, if another object impinges strongly on the awareness so as to draw it away from the rising and falling of the abdomen, this object must be clearly noted. For example, if a loud sound arises during your meditation, consciously direct your attention toward that sound as soon as it arises. Be aware of the sound as a direct experience, and also identify it succinctly with the soft, internal, verbal label “hearing, hearing.” When the sound fades and is no longer predominant, come back to the rising and falling. This is the basic principle to follow in sitting meditation.

15. What is the best way to make the verbal label?

There is no need for complex language. One simple word is best. For the eye, ear and tongue doors we simply say, “Seeing, seeing…,” or, “hearing, hearing…” or, “tasting, tasting . . . .”

16. What are some ways to note sensations in the body?

For sensations in the body we may choose a slightly more descriptive term like “warmth,” “pressure,” “hardness” or “motion.”

17. How should you note mental objects?

Mental objects seem to present a bewildering diversity, but actually they fall into just a few clear categories, such as “thinking,” “imagining,” “remembering,” “planning” and “visualizing.”

18. What is the purpose of labeling?

In using the labeling technique, your goal is not to gain verbal skills. Labeling helps us to perceive clearly the actual qualities of our experience, without getting immersed in the content. It develops mental power and focus.

19. What kind of awareness do we seek in meditation, and why?

We seek a deep, clear, precise awareness of the mind and body. This direct awareness shows us the truth about our lives, the actual nature of mental and physical processes.

Ending Your Meditation

20. After one hour of sitting, does our meditation come to an end?

Meditation need not come to an end after an hour of sitting. It can be carried out continuously through the day.

21. How should you get up from sitting meditation?

When you get up from sitting, you must note carefully, beginning with the intention to open the eyes: “intending, intending”; opening, opening.” Experience the mental event of intending, and feel the sensations of opening the eyes. Continue to note carefully and precisely, with full observing power, through the whole transition of postures until the moment you have stood up, and when you begin to walk.

22. Besides sitting and walking, what else should you be aware of throughout the day?

Throughout the day you should also be aware of—and mentally note—all other activities, such as stretching, bending your arm, taking a spoon, putting on clothes, brushing your teeth, closing the door, opening the door, closing your eyelids, eating and so forth. All of these activities should be noted with careful awareness and a soft mental label.

23. Is there any time during the day in when you may relax your mindfulness?

Apart from the hours of sound sleep, you should try to maintain continuous mindfulness throughout your waking hours.

24. It seems like a heavy task to maintain continuous mindfulness throughout the day.

This is not a heavy task; it is just sitting and walking and simply observing whatever occurs.

Retreat & Walking Meditation

25. What is the usual schedule during a retreat?

During a retreat it is usual to alternate periods of sitting meditation with periods of formal walking meditation of about the same duration, one after another throughout the day.

26. How long should one walking period be?

One hour is a standard period, but 45 minutes can also be used.

27. How long a pathway do retreatants choose for formal walking?

For formal walking, retreatants choose a lane of about twenty steps, and then walk slowly back and forth along it.

28. Is walking meditation helpful in daily life?

Yes. A short period—say ten minutes of formal walking meditation before sitting—serves to focus the mind. Also, the awareness developed in walking meditation is useful to all of us as we move our bodies from place to place in the course of a normal day.

29. What mental qualities are developed by walking meditation?

Walking meditation develops balance and accuracy of awareness as well as durability of concentration.

30. Can one observe profound aspects of the dhamma [dharma] while walking?

One can observe very profound aspects of the dhamma while walking, and even get enlightened!

31. If you don’t do walking meditation before sitting, is there any disadvantage?

A yogi who does not do walking meditation before sitting is like a car with a rundown battery. He or she will have a difficult time starting the engine of mindfulness when sitting.

Walking Meditation & Mindful Movement

32. During walking meditation, to what process do we give our attention?

Walking meditation consists of paying attention to the walking process.

33. When walking rapidly, what should we note? Where should we place our awareness?

If you are moving fairly rapidly, make a mental note of the movement of the legs, “Left, right, left, right,” and use your awareness to follow the actual sensations throughout the leg area.

34. When moving more slowly, what should we note?

If you are moving more slowly, note the lifting, moving and placing of each foot.

35. Whether walking slowly or rapidly, where should you try to keep your mind?

In each case you must try to keep your mind on just the sensations of walking.

36. When you stop at the end of the walking lane, what should you do?

Notice what processes occur when you stop at the end of the lane, when you stand still, when you turn and begin walking again.

37. Should you watch your feet?

Do not watch your feet unless this becomes necessary due to some obstacle on the ground; it is unhelpful to hold the image of a foot in your mind while you are trying to be aware of sensations. You want to focus on the sensations themselves, and these are not visual.

38. What can people discover when they focus on the sensations of walking?

For many people it is a fascinating discovery when they are able to have a pure, bare perception of physical objects such as lightness, tingling, cold and warmth.

39. How is walking usually noted?

Usually we divide walking into three distinct movements: lifting, moving and placing the foot.

40. How can we make our awareness precise?

To support a precise awareness, we separate the movements clearly, making a soft mental label at the beginning of each movement, and making sure that our awareness follows it clearly and powerfully until it ends. One minor but important point is to begin noting the placing movement at the instant that the foot begins to move downward.

41. Is our knowledge of conventional concepts important in meditation?

Let us consider “lifting.” We know its conventional name, but in meditation it is important to penetrate behind that conventional concept and to understand the true nature of the whole process of lifting, beginning with the intention to lift and continuing through the actual process, which involves many sensations.

42. What happens if our effort to be aware of lifting is too strong, or alternatively, too weak?

If our effort to be aware of lifting the foot is too strong it will overshoot the sensation. If our effort is too weak it will fall short of this target.

Developing Insight & Concentration

43. What happens when effort is balanced?

Precise and accurate mental aim helps balance our effort. When our effort is balanced and our aim is precise, mindfulness will firmly establish itself on the object of awareness.

44. What mental factors must be present for concentration to develop?

It is only in the presence of three factors—effort, accuracy and mindfulness—that concentration develops.

45. What is concentration?

Concentration is collectedness of mind: one-pointedness. Its characteristic is to keep consciousness from becoming diffuse or dispersed.

46. What will we see as we get closer and closer to the lifting process?

As we get closer and closer to this lifting process, we will see that it is like a line of ants crawling across the road. From afar the line may appear to be static, but from closer up it begins to shimmer and vibrate.

47. As we get even closer, what will we see?

From even closer the line breaks up into individual ants, and we see that our notion of a line was just an illusion. We now accurately perceive the line of ants as one ant after another ant after another ant.

The Progress of Insight

48. What is “insight”?

“Insight” is a mental factor. When we look accurately, for example, at the lifting process from beginning to end, the mental factor or quality of consciousness called “insight” comes nearer to the object of observation. The nearer insight comes, the clearer the true nature of the lifting process can be seen.

49. What is the progress of insight?

It is an amazing fact about the human mind that when insight arises and deepens through Vipassana, or “insight meditation practice,” particular aspects of the truth about existence tend to be revealed in a definite order. This order is known as the progress of insight.

50. What is the first insight that meditators commonly experience?

Meditators comprehend, not intellectually or by reasoning but quite intuitively, that a process such as lifting is composed of distinct mental and material phenomena occurring together, as a pair. The physical sensations, which are material, are linked with, but different from, the awareness, which is mental.

51. What is the second insight in the classical progress of insight?

We begin to see a whole succession of mental events and physical sensations, and to appreciate the conditionality that relates mind and matter. We see with the greatest freshness and immediacy that mind causes matter, as when our intention to lift the foot initiates the physical sensations of movement, and we see that matter causes mind, as when a physical sensation of strong heat generates a wish to move our walking meditation into a shady spot. The insight into cause and effect can take a great variety of forms. When it arises, though, our life seems far more simple to us than ever before. Our life is no more than a chain of mental and physical causes and effects. This is the second insight in the classical progress of insight.

52. What is the next level of insight?

As we develop concentration, we see even more deeply that these phenomena of the lifting process are impermanent and impersonal, appearing and disappearing one by one at fantastic speed. This is the next level of insight, the next aspect of existence that concentrated awareness becomes capable of seeing directly. There is no one behind what is happening; the phenomena arise and pass away as an empty process, according to the law of cause and effect. This illusion of movement and solidity is like a movie. To ordinary perception it seems full of characters and objects, all the semblances of a world. But if we slow the movie down we will see that it is actually composed of separate, static frames of film.

This interview first appeared on Nibbana.com.