Tsuneo Iwasaki (1917–2002) was born on July 9, 1917, into a Kyoto family that highly valued education. Along with his six sisters, he, too, became a teacher of biology. He did not start painting until the sixth decade of his life, after retiring from his career as a biologist. Over the following years, Iwasaki revealed ever deeper layers of his motivations and creative process, including the original question that inspired him to take up a paintbrush: “How do I pass on what I’ve learned about life, death, and healing?” He passed away without knowing that His Holiness the Dalai Lama would one day bless his art for its power to illuminate resonances in Buddhist and scientific views of reality.

Iwasaki’s compassion for all beings was forged in the crucible of war. Like many veterans, he preferred not to dwell on details of his wartime experience, but it was clear to me that the war revealed the depth of his commitment to life. He was twenty-four years old on April 10, 1942, when he began serving the Japanese Imperial Army. One among ninety thousand Japanese troops, he was deployed under Army General Hitoshi Imamura at the deep-sea harbor of Rabaul, New Guinea. After the war, these troops were held in internment camps by the Allied forces of Australia, who did not provide much food. Many of the troops were farmers, so they became self-sufficient, preventing most from dying of starvation. Iwasaki also mentioned how they ate snakes and insects.

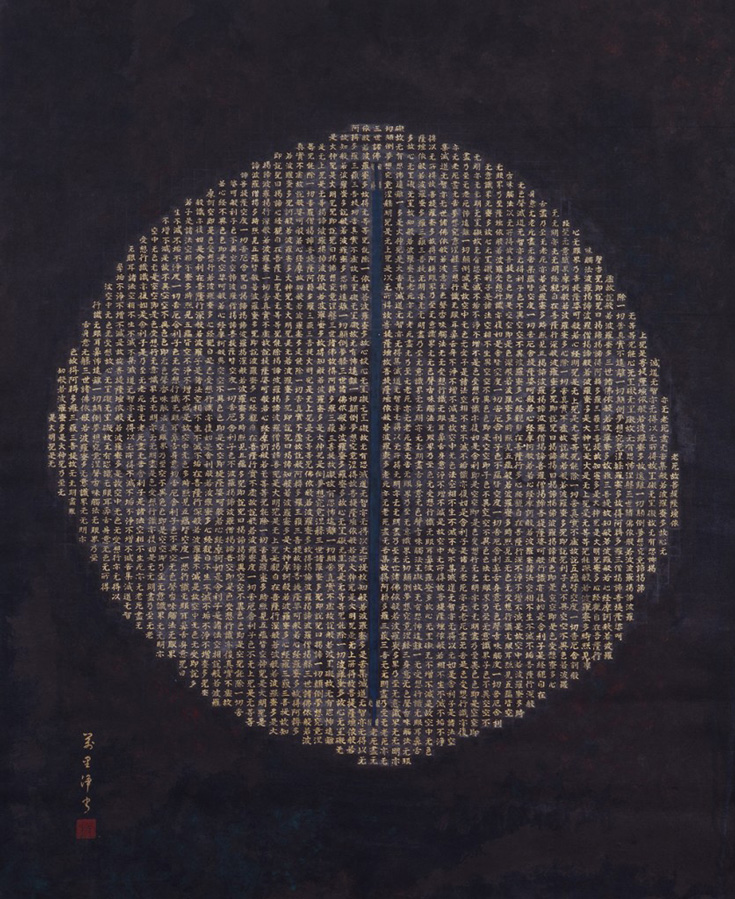

In the decades after his return to Japan, as he pursued a career as a teacher and biologist, Iwasaki looked for ways to transform his suffering on the front lines of war into compassion for all beings. He looked to different Buddhist teachings and practices for help in this regard, and nothing was more potent for him than his encounter with the Heart Sutra. Iwasaki engages the contemporary imagination by using the sacred words of this text to paint visual tropes of science, among them a hydrogen atom, the Andromeda galaxy, a strand of DNA, and a cosmic representation of E = mc2. He weaves them together with Buddhist tropes of compassion such as Baby Buddha, Amida Buddha, Kannon, and Fudo Myo-o. Through fusing these two modes of viewing reality, Iwasaki’s art reveals the jewels buried deep in the interstices of the Heart Sutra.

Iwasaki began scripture copying practice with focused intent when he was sixty-three. Gratitude and concern for the well-being of all flowed through his heart into the tip of his brush as he copied the Heart Sutra nearly two thousand times. Keenly aware of the suffering in his midst and the diminishing numbers of people who learn Buddhist teachings through daily activity, he channeled the intimacy he cultivated with the text into an innovative way to make the teachings visually accessible.

So it was, at the age of seventy, Iwasaki began to shape the characters of the scripture into images that convey the meaning of the scripture. In so doing, he extended the contemplative practice of scripture copying and launched the tradition of tiny-character painting in a new direction. Technically called saimitsu, the tiny characters can create the effect of a fluid line. Regular sized characters in scripture copying are usually about fifteen millimeters. Saimitsu tiny characters are five millimeters or less. Iwasaki favored two-, two-and-a-half-, and three-millimeter characters for most of his paintings. He made templates with millimeter markings to ensure he maintained uniform size. His modesty was palpable as he chuckled about a tedious quandary that challenged him with each painting. “I can’t finish the sutra before I finish the image, and I can’t finish the image before I finish the sutra!” So before he even put brush to paper, he precisely calculated the size of each character he would need to make an image. The numerous measurements involved were dauntingly intricate, and his success in the compositions revealed the benefit of his scientific training to be accurate with details and calculations. Calling himself a “Sunday carpenter,” he created a magnifying glass holder to help him see as he brushed each of the carefully calculated strokes. Having spent much of his life looking through microscopes, he was at home working in a miniature scale that required a magnifying glass.

Even after thirty years of doing calligraphy, painting, and studying Buddhist teachings, he explicitly articulated that he did not consider himself a “calligrapher, painter, nor Buddhist scholar.” He stressed that the quality of writing was not important to him, because his effort was simply about sharing Buddhist teachings through pictures.

I hold my palms together with a sense there is some awakened power guiding me. When I paint, it feels like I am on a pilgrimage, ‘Traveling Two Together.’ It’s like my hands are being guided and inspiration for ideas comes to me in dreams and other types of mysterious experiences. Doing this connects me to all beings.

Painting as a meditation, he showed us what the world looks like from the perspective of someone who experiences being an integral part of an interdependent whole. His art models for us how to look at a dewdrop and see the universe.

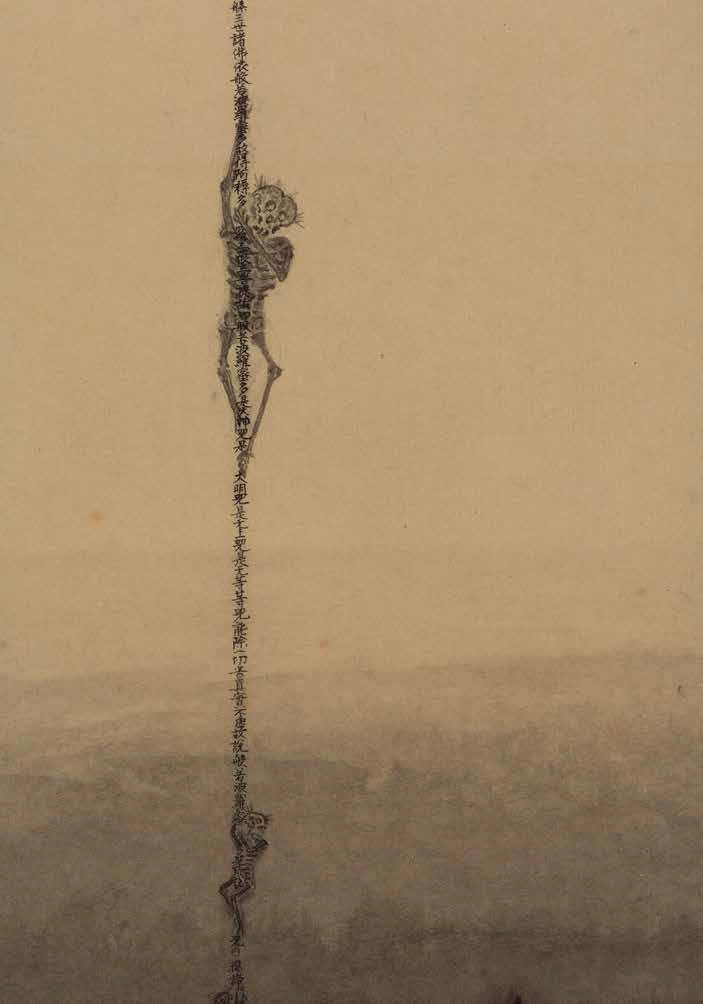

Climbing Out of Hell

Kannon, the goddess of compassion, pours nectar into hell to relieve suffering beings. Her elixir is a stream of Heart Sutra wisdom that offers a means of ascent for the skeletons climbing the luminous strands. Iwasaki references a popular Japanese novel by Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Kumo no Ito (The Spider’s Thread), in which so many people simultaneously attempt to climb out of hell on a spider’s thread that the web breaks from the weight of their greed. The artist casts wisdom as a power that can lift beings from hells of their own making.

Having served in the army in World War Two, Iwasaki has a visceral insight into the depths of suffering to which humans can descend. Indeed, in a stunning effort to accurately paint the angles of the bones of the skeletons, he served as his own model. At age seventy-five, he suspended a rope from a tree branch in his garden and videotaped himself climbing up and hanging on to the rope. He thereby painted himself among those in hell. The meticulous precision with which he renders the bones expresses an intimate care and tender respect for beings in hell. It also evokes the surgical skill required to remove afflictions that provoke suffering.

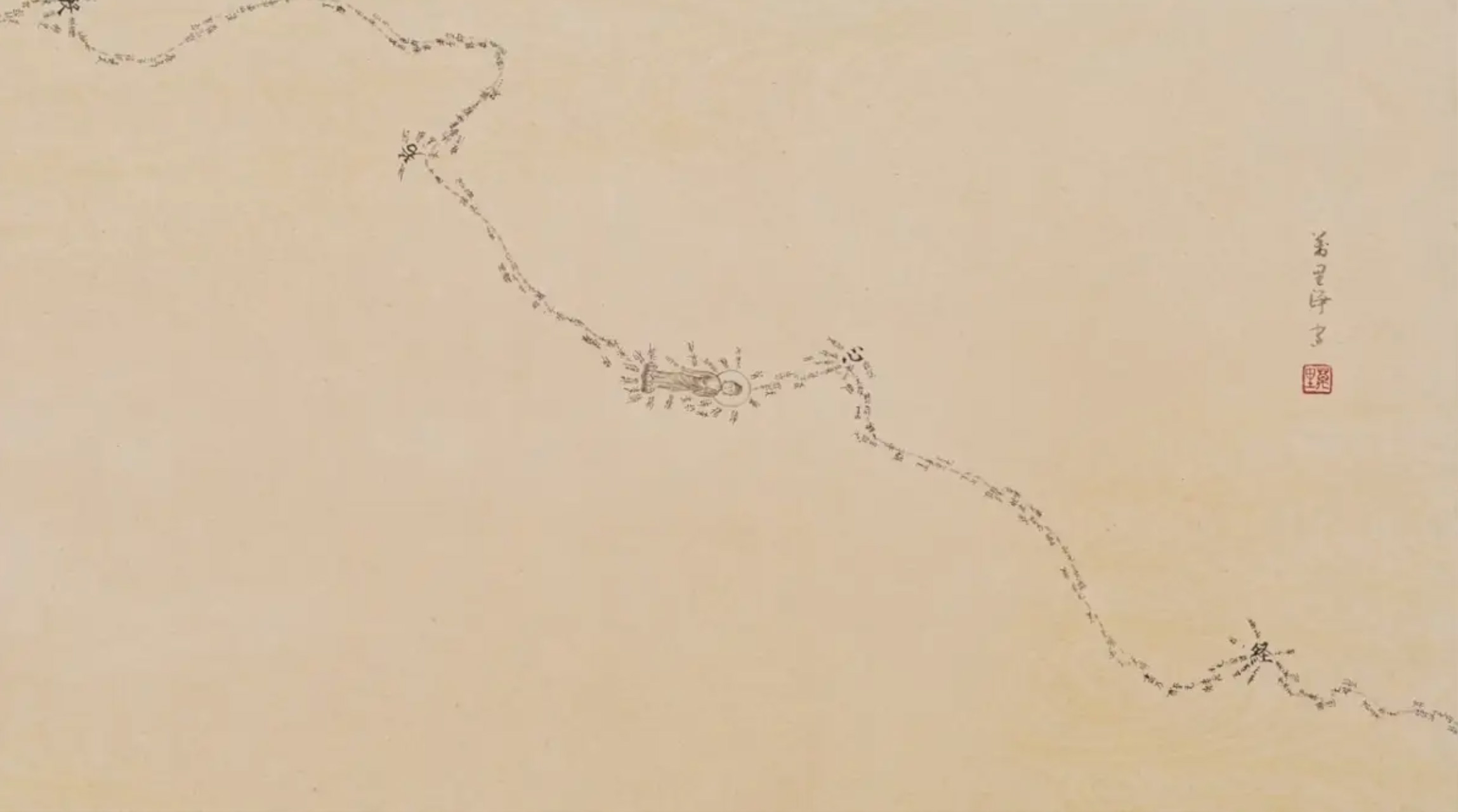

Do Ants Have Buddhanature?

Iwasaki transposed a famous Zen koan—“Do dogs have buddhanature?”—to make a delicious pun on the Japanese words “have” (ari) and “ant” (ari). Understanding the implications of “have” is the key to cracking the riddle, for the nature of dogs, ants, and even buddhas is a fluid and dynamic process, not an object that one might have. In this painting, the words of the Heart Sutra, in black ink on a tawny earthen ground, are ingeniously contorted into the shape of ants meandering across the horizon. By not showing a beginning or end to the procession, Iwasaki intimates the path is the journey. Iwasaki fed the ants in his garden so he could observe their behavior. A small cluster of ants carries a buddha, while others carry religious epigrams. This humorous personification interposes humans and insects in a way that challenges human hegemony and elevates minute arthropods.

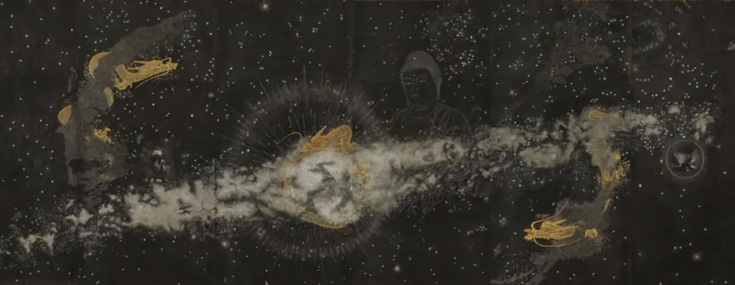

Big Bang: E = mc2

Iwasaki’s magnum opus, Big Bang: E = mc2, illustrates the cosmic activity of transformation with the dynamic energy and forces at work in the Heart Sutra. Impermanence on a galactic scale shimmers across the seventeen-foot span that traverses six scrolls. The aesthetic rhythm of this painting is both thunderous and delicate as the eye dances across the cosmos and canticles through the galaxies. The darkness pulses with a vacuum of silence, scintillating with gold crescendos. Intricately rendering the 3,588 characters required to copy the Heart Sutra thirteen times—thirteen being a nondivisible whole number—Iwasaki draws the viewer into intimacy with an infinite vista. Like a massive constellation for radiating the light of compassion throughout interstellar space, the cosmos is infused with a gossamer Buddha of Infinite Light, Amida. By summoning this luminous Buddha, Iwasaki invokes the power of wisdom and compassion available in our cosmos. He affirms our cosmos is a Pure Land, a womb that embraces with compassion and nourishes with wisdom.

Amplifying its numinous nature, Iwasaki enhances the universe with golden dragons, revered as powerful protectors of seekers of enlightenment. Dragons wield adamantine wisdom, surging through space with the energy of emptiness, the source of all forms.

Although Iwasaki alludes to origins with “Big Bang” in the title, he associates it with Einstein’s 1905 theory of special relativity equation: E = mc2. In so doing, he attests that origins are transformation and interprets E = mc2 as scientific language to articulate the Heart Sutra’s teaching: “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form.” After completing this painting, Iwasaki reflected, “The karmic tie that binds all beings brings about the cycle of life and death. I, too, am bound by this recurrence of the life cycle. The occurrence of the big bang gave rise to my being. For this I simply bow to the Universe.” Through this masterpiece, Iwasaki enraptures viewers to behold the boundlessness of the universe and experience our interrelatedness, thereby healing the delusion of separateness that causes so much loneliness and despair.

Adapted from Painting Enlightenment: Healing Visions of the Heart Sutra by Paul Arai (Shambhala Publications, September 2019)