Every day I lurk and listen to scholars of Eastern religions on the academic forum Buddha-L, taking notes when their exchanges clarify some arcane matter of Pali grammar or touch upon sutras I feel I should study. One day the forum’s moderator, scholar Richard Hayes, provided an examination of the meaning and implications of the Sanskrit word maana that I found insightful.

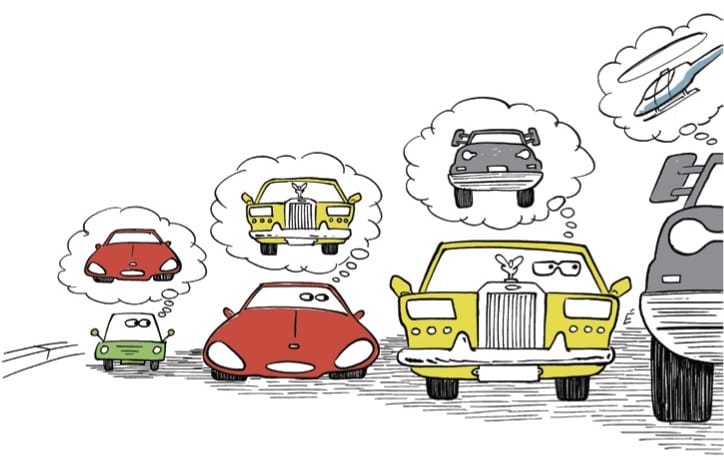

“According to some Abhidharma traditions,” wrote Hayes, “one of the last obstacles that a person overcomes on the road to liberation is maana, usually translated as pride… In Abhidharma literature, maana is described as the tendency to think in one of three ways: 1) Thinking of oneself as better than others; 2) Thinking of oneself as inferior to others; and 3) Thinking of oneself as equal to others… The Sanskrit word is derived from a verbal root that means to measure. So maana is the act of measuring, or perhaps comparing. It is the kind of thinking we do when we wonder, whether to ourselves or out loud, ‘Is mine bigger than yours? Is mine as good as yours?’ Abhidharma is right, I think, in pointing out that all of us who are not arhants (and I’m guessing that would be several of us on Buddha-L) are busy measuring ourselves against the standards set by others.”

Hayes added, “Having acknowledged that we are all prone to looking around to see how well we stack up in comparison to others (for we are, after all, social animals, and we learn best by imitation) and whether we’re still okay in the imagined eyes of other beholders, even those we pretend to disregard, I think one can cultivate the habit of focusing so much on flaws that one fails to see what is good in things.”

We do not judge these thoughts and feelings, or ourselves for having them. We don’t embrace them or run from them.

Every dimension of our lives—personal and professional, even our miscellaneous list of “likes” and “dislikes”—is saturated with maana. From our earliest years of receiving grades that measure our academic progress to the promotions we strive for in our jobs, maana is an activity we engage in every minute of every day.

If we did not do this measuring in the realm of conventional reality, we would be unable to function socially or practice “right effort” when we see our discipline becoming lax. But maana can be spiritually damaging to others and ourselves (I’m thinking of an interview in which the Dalai Lama was asked, “How shall we deal with self-hatred?” He found the question so confounding—almost an oxymoron for a Buddhist who knows an enduring “self” is an illusion—that he asked the interviewer to explain what in the world “self-hatred” could possibly mean); and it is at odds with the precepts that we “Do not speak of others’ errors and faults” and “Do not elevate self and blame others.”

Fortunately, in the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (“Great Discourse on the Establishing of Awareness”) the Buddha offers an antidote for maana that I have found to be infallible: namely, “contemplating mind as mind… mind-objects as mind-objects.” The mind, being the exotic phenomenon that it is, churns out thoughts and feelings 24/7 that are wholesome and unwholesome, kind and unkind. We have to sit patiently with this extraordinarily colorful mind (and ourselves). All manner of thoughts and memories arise: “That hurts,” or “That was nice”; “I’m great,” or “I’m a loser”; or as we read in the Dhammapada, “He abused me; he beat me; he defeated me; he robbed me.” We do not judge these thoughts and feelings, or ourselves for having them. We don’t embrace them or run from them. We simply let them be, observing how—like all impermanent things—they are ephemeral, transitory, like bubbles in a stream, rising and fading away. A feeling of anger at someone might arise, but we know that we are not this anger. If we do not grasp at it or cling to it, its energy will dissipate. And as we inspect each mind-object, we are free, of course, to pursue those that are wholesome, kind, and enable us to alleviate the suffering of others, allowing those thoughts to become actions.

As we contemplate ourselves and others, the Buddhist approach is to do so with egoless listening to how the “other” presents herself, phenomenologically, to us moment by moment. Another name for such selfless listening is love.

The result of this practice is an opening of one’s heart to others, and to ourselves. It also leads to “epistemological humility,” which is a healthy skepticism about what we think we know. For example, last spring my wife and I celebrated our fortieth wedding anniversary. I have known her since we were twenty years old. I have seen her change over more than four decades. I know her as a friend, mother, confidante, a spiritual seeker, a former teacher and social worker. I know her medical history and the results of her DNA testing. I know her human birth to be a blessing unknown to either gods or hungry ghosts. But I can never know all her thoughts, feelings, and experiences, even after a lifetime spent together. Do we ever truly know another well enough to judge them as better, equal, or inferior to ourselves when each of us is, ontologically, a ceaseless play of patterns—physically, emotionally, perceptually, and in respect to consciousness? I think not. To some degree, the “other” remains a wonderful mystery that ever outstrips our concepts, feelings, and perceptions of her. My wife, therefore, is always new and surprising to me. We can say the same about ourselves. And in the face of such mystery, as we contemplate ourselves and others, the Buddhist approach is to do so with egoless listening to how the “other” presents herself, phenomenologically, to us moment by moment. Another name for such selfless listening is love.

This, I believe, is what is meant in the statement attributed to Shakyamuni Buddha (perhaps apocryphal but certainly in the spirit of dharma) that, “You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.”