Kodo Nishimura introduces himself as a Buddhist monk, a makeup artist, and a member of the LGBTQ+ community—but defining a self is not so simple as that. When someone asks Nishimura if he’s gay, transgender, or queer, he feels stuck for an answer, and doesn’t doubt that many others are similarly frustrated. “We should know,” Nishimura writes, “that our own awareness of being is what makes us us.”

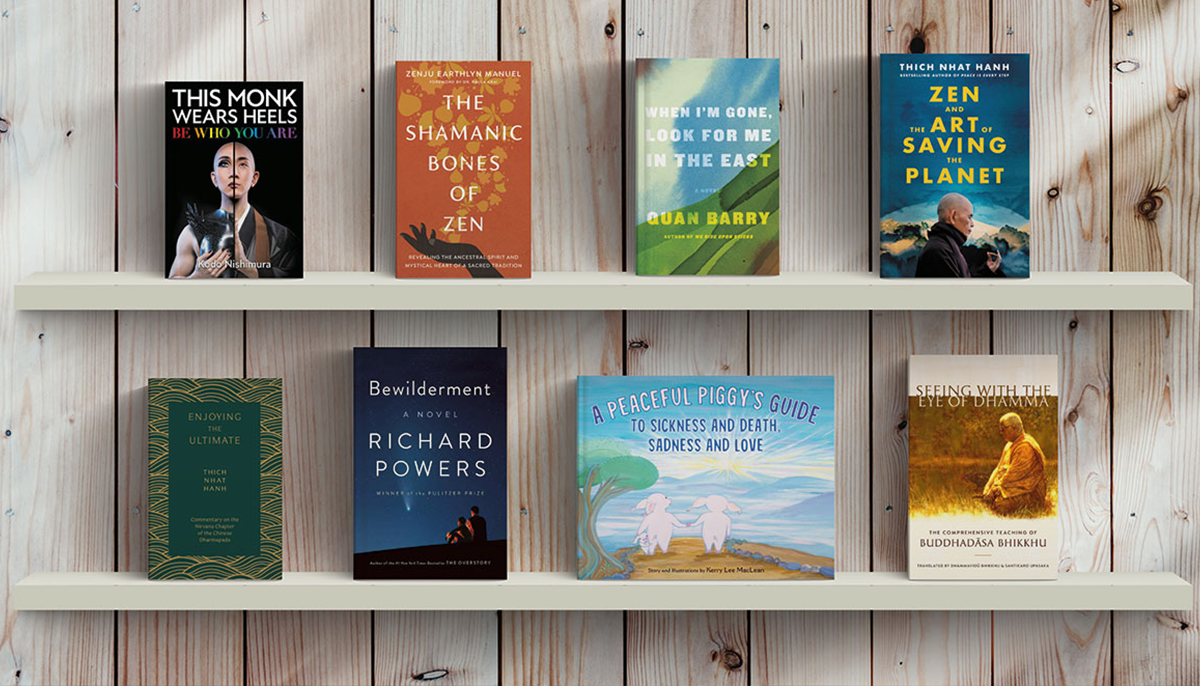

Much of the profundity of Nishimura’s book This Monk Wears Heels (Watkins) arises out of his training in Jodo Shu, a branch of Pureland Buddhism founded in twelfth-century Japan. Nishimura brilliantly intersperses personal memoir with gentle writing exercises for exploring one’s heart alongside excerpted sutras that support Nishimura’s seemingly untraditional path. Nishimura demonstrates that living authentically is utterly necessary. Only by intimately knowing and accepting who you are can you be your true self; running from yourself drives insight of every kind into shadow. You must question everything, says this monk in heels, “Even if it is a pillar of teaching.”

In the spirit of unflinching questioning like Nishimura’s, Zen teacher Zenju Earthlyn Manuel raises an important question of her own in The Shamanic Bones of Zen (Shambhala): what might we gain from being open to indigenous or shamanic interpretations of Buddhist practice? Manuel understands that suggesting Zen might be “shamanic” raises all kinds of fears and resistance among practitioners—worries about New-Agey vibes, witchcraft, Voudou, and more. But such resistance is part of why the question must be raised.

Manuel deftly threads the needle of scholarly inquiry with the experience of zazen, a deeply somatic, ritualistic way of being that brings her—and possibly all of us—into deep communion with our ancestors: humans, animals, plants, stars, stones. Zazen is not, after all, secular meditation. There’s something more to it—embodied ritual, shared across space and time with all of these ancestors—which brings about transformation and healing. It’s visceral enactment and medicine, a living tradition that runs far deeper than rational thought.

In her gorgeous new novel, When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East (Pantheon), Quan Barry takes us straight into the heart of Mongolia, across its grasslands and deserts to the foot of its mountains in her exploration of a powerfully mysterious relationship between twin brothers and their own shamanic ancestors. Barry investigates each of the twins’ relationship with monasticism and the confluence of “past” and “current” lives. Sentence for sentence, Barry’s writing is bright and searing, and this reader is as haunted as the twin brothers by the riddle of selfhood as Barry presents it. Is one person three? Are three people one? Whose duty is whose?

Importantly, the novel is also powerfully instructive on the politics and history that have shaped these brothers’ and their companions’ lives in deeply painful ways—and how a single frostbitten boy fleeing his homeland or a monk who has fallen in love with a poor girl might transcend the forces that attempt to bind and define them.

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet (HarperOne) presents teachings by Thich Nhat Hanh interspersed with commentary by his student Sister True Dedication. “The beauty of the earth is a bell of mindfulness,” Thich Nhat Hahn said, and waking up to this beauty is waking up to the truly transformational compassion that the crises of ecological destruction, climate breakdown, inequality, and injustice all require. We learn that meditating is not a way to distract or numb one’s self to such suffering, but a way to experience it directly, and be changed by it. Amidst despair and seemingly insurmountable difficulty—and indeed, the certain impermanence of every civilization and creature—the one thing each of us has the power to change is our mind.

Enjoying the Ultimate (Palm Leaves Press) is composed of the first English translation of “The Chapter on Nirvana” of the Chinese Dhammapada, plus commentary on it by Thich Nhat Hanh. The translator, Sister True Virtue, uses the word “ultimate” in the title to translate a Vietnamese expression that means “space outside of space” because nirvana is beyond any concepts at all—including concepts of space and time. Nirvana cannot be understood intellectually, only experientially. It’s not a place one is on the way to, but a way of being—an aimless, joyful wandering. Nirvana neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing we say about it will be correct. And yet, here is this book full of words about nirvana—which guides us toward understanding with pratyakssa pramaanna, direct perception.

If Buddhism is a practice of exploring space beyond space, of recognizing the truth of suffering, of questioning the limits of human knowledge, and of hearing that bell of mindfulness, which is the beauty of Earth, then Richard Powers’ Bewilderment (W. W. Norton & Company) is a “Buddhist novel.” Powers tells the story of a widower, Theo, and his young son, Robin, who is perhaps appropriately maladjusted to and confused by the sick culture he’s expected to navigate if not serve. Together they explore the possible worlds that Theo has assembled in his career as an astrobiologist, painfully bearing witness to the transformation and loss of life on planet earth. Just when it seems insight is at hand, the flux of their lives shifts again, demonstrating that there’s no nirvana without the phenomena of forms, without our very bodies, or without heartbreak.

Kerry Lee MacLean has dedicated her new children’s book, A Peaceful Piggy’s Guide to Sickness and Death, Sadness and Love (Wisdom), to her grandchildren, who have spent all their lives, she writes, living with sick family members. What can children do when someone they love gets sick? How can the anxious, sad, or confused child connect with their feelings and bodies amidst such difficulty? Peaceful Piggy offers a model of calm presence and gentle exercises, such as walking with great attention on the bottoms of the feet, lying on the ground like a starfish, and making a simple flower arrangement or a “mind jar.” With each exercise as beneficial for grown-ups as for their children, this book is a beautiful tool for directly experiencing and talking about sickness, death, and dying—not morbid or forbidden topics, but part of life itself.

Seeing with the Eye of Dhamma (Shambhala) is by Buddhadasa Bhikku (1906–1993), one of the most influential Thai Buddhists of the twentieth century. This comprehensive text, which is focused on “life as cultivation of mind,” unpacks Theravada teachings—some of which Buddhadasa Bhikku interprets in nontraditional ways. Beginning with a deep inquiry into the human senses, he guides the reader through incisive questions about the purpose of a human life and the dangers of ignoring spiritual cultivation. He teaches that through sincere and consistent cultivation of the mind and unceasing and increasingly subtle and piercing inquiry into the nature of experience and suffering, we can begin and continue to awaken. It’s not just a personal inclination, but a profound duty, to train the mind, to advance and grow, to cease making foolish mistakes based on superstition, and to minimize suffering.