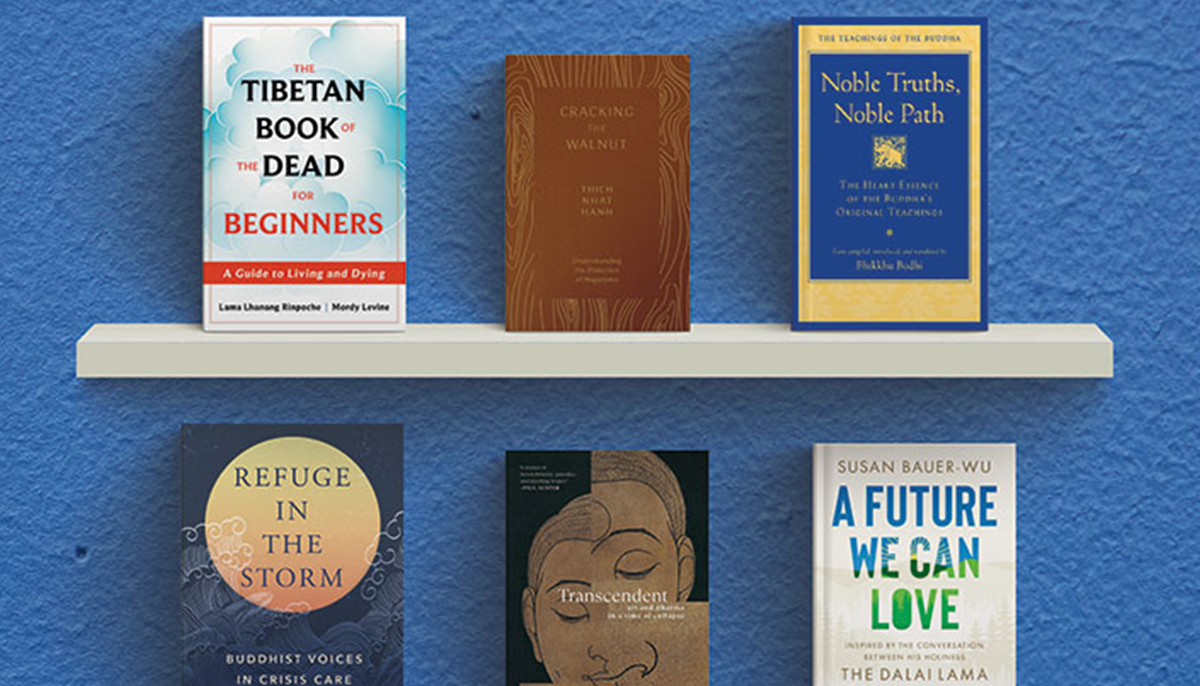

Years ago, I picked up The Tibetan Book of the Dead but found it a little inaccessible. Now, in clear prose, The Tibetan Book of the Dead for Beginners (Sounds True) explains the heart of it, helping us face the reality of our mortality with wisdom and compassion. The mysteriously simple idea is that living with joy and kindness allows us to approach death with confidence and ease. While in Western culture, discussion of death is avoided, in the Tibetan tradition it is acknowledged daily in teachings meant to guide people toward ethical, happy lives. Authors Lama Lhanang Rinpoche and Mordy Levine say, “If you study death, it can be a transforming, liberating event. If you don’t, it can be very difficult.” This book is a gentle, thoroughgoing guide, which includes compelling explanations of karma, selfhood, and consciousness, as well as practices, drawn from the original text and tested across generations, which help us embrace the unknown.

Nagarjuna, who’s believed to have lived in India from 150 to 250 CE, is one of Buddhism’s most preeminent philosophers. A strong advocate of the Mahayana movement, he’s considered the founder of the Madhyamaka school, which asserts that all phenomena are empty of a solid, independent existence. I’m always grateful for commentary and analysis of Nagarjuna’s teachings, and Thich Nhat Hanh’s Cracking the Walnut: Understanding the Dialectics of Nagarjuna (Parallax) is particularly inspired. The dense philosophy of Nagarjuna’s Treatise on the Middle Way can seem like metaphysical speculation, but Thich Nhat Hanh—with his encouraging warmth—helps readers get to the heart of the matter and actually experience a suspension of dualistic thought. We touch reality when we recognize that nothing has self-nature—that there is no birth or death, no permanence or annihilation, no coming or going.

American Theravada Buddhist monk and eminent translator Bhikkhu Bodhi’s new book is Noble Truths, Noble Path: The Heart Essence of the Buddha’s Original Teachings (Wisdom Publications). It is an anthology of elegant, reader-friendly translations of suttas from the Samyutta Nikaya in the Pali canon. Bhikkhu Bodhi focuses on verses representing the essence of the Buddha’s teachings, which he describes as a summary of two interrelated structures: the four noble truths, which covers the doctrine, and the eightfold path, which handles the training. Reading this book, it becomes very clear just how fundamental the four noble truths are in the Buddha’s discourses. Again and again, the suttas bring the practitioner back to them, and the primary response that is called for is practice. With precision and wisdom, Bhikkhu Bodhi’s introductions to each set of verses beautifully elucidate Pali terminology, including for example, khandha, dukkha, even aggregate. This book is a true gift.

Refuge in the Storm: Buddhist Voices in Crisis Care (North Atlantic) is essential reading for those who work in crisis care. It is a compilation of sacred work about sacred work. These twenty-four essays have been compiled and edited by Nathan Jishin Michon, Buddhist priest, chaplain, teacher, and writer, to support both individuals and communities. The chapters range in perspective and purpose from the pragmatic to the sublime, from the tenets of deep ecology to the training path for Buddhist chaplains with guidelines for self-care and preventing burnout. On these pages, there’s a depth of experience, maturity, and wisdom across a range of international care providers, including chaplains, nurses, medical technicians, psychologists, professors, and more. They have sometimes anguished but always clear-eyed and compassionate responses to illness, dying, relationship conflict, racial injustice, immigration, and natural disasters. The challenges of crisis care seem daunting, yet as one of the book’s authors, Shushin R. A. Peterson, writes: “We are all capable of this work.”

I don’t have much extra reading time, but I read Transcendent: Art and Dharma in a Time of Collapse (Melville House) twice. In many ways, this book by cultural critic and novelist Curtis White is a howl raging against infuriating injustices of the day. (Economic inequality is one note he hits resoundingly.) Yet his primary focus is on Buddhism’s failure to resist the gravitational pull of empiricism and quantification and how this may be diminishing the dharma—narrowing and foreclosing the practice, including among significant Buddhist teachers. Secular Buddhism, the “big science” Buddhism of the mindfulness movement, misses what has long been alive, elusive, and generative in the tradition, as well as in the arts, including music, film, and poetry. With urgency, warmth, and incisive prose, White discusses how we got here and what’s at stake, questioning what it is we’re practicing if the practice is apologetic, devoid of mystery, and reduced to something that helps us adjust more comfortably to a world of delusion and harm.

Perhaps this sounds familiar: “The constant drip, drip, drip of terrible headlines can begin to feel normal…yet the suffering feels too great to bear, so I turn away. It isn’t that I don’t care but that I feel helpless.” So writes Susan Bauer-Wu, president of the Mind & Life Institute, in her introduction to A Future We Can Love: How We Can Reverse the Climate Crisis with the Power of Our Hearts and Minds (Shambhala), which brings the eighty-five-year-old Dalai Lama and eighteen-year-old activist Greta Thunberg into dialogue. Yet, if there is medicine for despair and anxiety about climate change, it can be found in this book. In some respects, it is a primer on the science behind the crisis, and in others it is a pointed and clear reminder that we can and indeed must address climate change not just technologically, but also—and perhaps primarily—from within. As we work to redress the complex harms of planetary destruction, A Future We Can Love is an empowering read.

The meaning of life is life itself, in the backyard. So says writer Miki Sakamoto in Zen in the Garden: The Japanese Art of Meditative Gardening (Scribe), describing her suburban yard not far from the foothills of the Bavarian Alps, in Germany. “The point of the Zen approach to gardening is not self-expression,” she writes, “but rather the changes that the work creates in you.” In this deceptively simple book, Sakamoto details observations of aphids and fireflies, tomatoes and cabbages, roses and palms. And there is such a bittersweet tale of a blackbird! “The garden is alive in its own right,” she says. “It is not just an expression of my desires.”

Yale Buddhist chaplain Sumi Loundon Kim’s newest family-oriented book is Goodnight Love: A Bedtime Meditation Story (Bala Kids). With sweet, spare prose, she guides the adult and child reader in a metta (loving-kindness) practice at the end of the day, just before sleep. “We radiate kindness upward to the skies,” writes Kim, “and downward to the depths, outward and unbounded.” Artist Laura Watkin’s illustrations of two sloths bidding goodnight to the gorgeous world around their little tree house beautifully evokes a sense of wonder and gratitude for the richness of life. I want—and I want my own children—to memorize this book like a prayer. I cannot imagine a better story-time ritual for closing the day to help ensure a happy, peaceful sleep and steadiness of heart and mind.