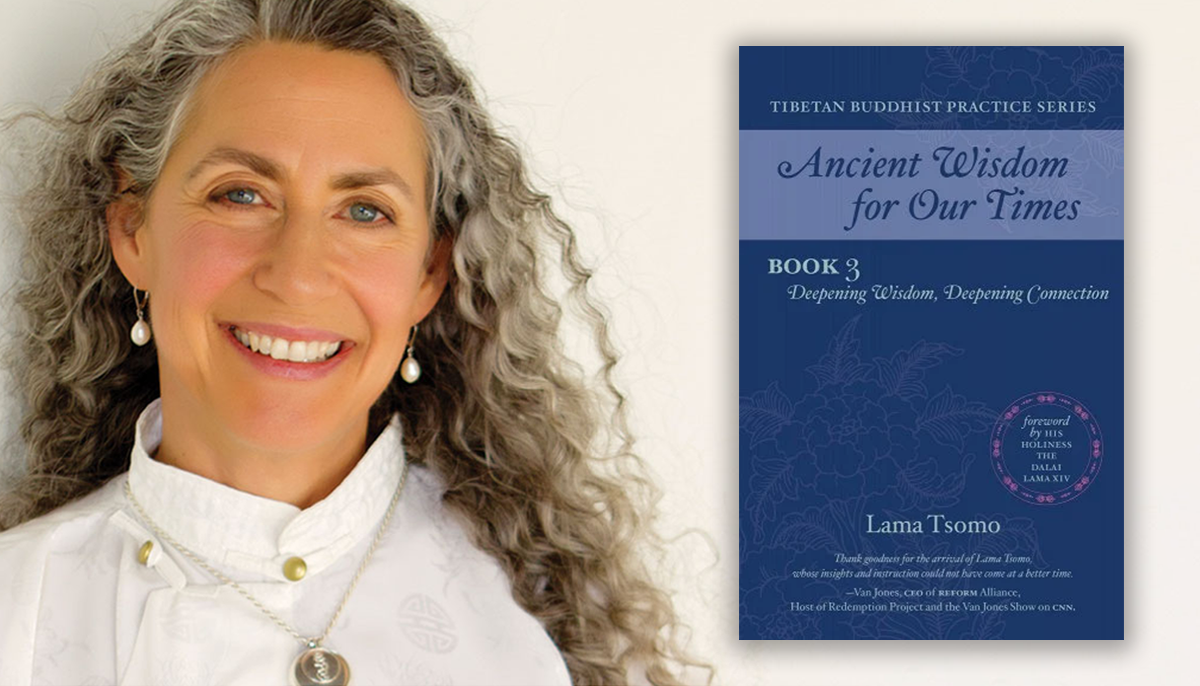

Lama Tsomo is a teacher, psychotherapist, and author who has just released Book 3 of her “Tibetan Buddhist Practice” series, published by Namchak Publishing. The series is titled Ancient Wisdom for Our Times, and this new volume is called Deepening Wisdom, Deepening Connection. (The first two volumes are titled, provocatively, Why Bother? An Introduction, and Wisdom and Compassion (Starting with Yourself).)

I recently had an opportunity to speak with Lama Tsomo for The Lion’s Roar Podcast. The following is an edited excerpt of our conversation, which will be shared in full in the weeks ahead.

Thank you so much for joining me, Lama Tsomo.

I’m so happy to be here.

Congratulations on this new book. Does one need to have read the “prequels,” as it were?

Well it does progress from one book to the next. It depends partly on your level of practice. But I’ve recently heard from people who have had a sneak preview, and despite my saying that this is a progression and a beginner can really benefit from going step by step through it. It’s been found quite accessible. I’m thinking of one person in particular a couple of days ago, and other people have said the same: it’s actually accessible even for beginners. And then they find they wanna go back to the prequels and find out more. So, you can kind of go at it from either direction.

The book covers two main subject areas. One is the “four boundless qualities,” also known as the brahmaviharas, or the Divine Abodes, or the four immeasurables. These are equanimity, loving-kindness, compassion, and sympathetic joy. And it should be noted that all of these are related to us as things that should be considered for our purposes, boundless. (Which is very lovely.) And then the second part of the book is Vipassana, or Insight meditation. Why these two areas together, and how do they relate to your title, Deepening Wisdom and Deepening Connection?

Well, they dovetail together. It’s almost like two wings of a bird, if you will. So as we’re seeing how we’re actually not separate — and that happens through Vipassana quite naturally, as you see how things really are — you understand that we all come out of the same ground. And so, that’s one wing. Then the other wing is the connection piece, where we feel through our hearts how we’re not separate. I like to include both of those in each meditation.

Throughout Buddhist practice, there are those two elements: the seeing for yourself how it actually is, that we’re not separate, and, then the feeling how we’re not separate.

You’ll find throughout Buddhist practice, no matter how high or how profound you get, there are those two elements: the seeing for yourself how it actually is, that we’re not separate, and, then the feeling how we’re not separate. I think especially in these times, that’s terribly important for us to feel and see for ourselves, because right now we’re feeling very separate; there’s a lot of us/them thinking. Everybody’s pointing fingers at each other and blaming each other for all the difficulties going on. And of course, that’s not producing a lot of great solutions, and doesn’t feel so great.

The thing that’s boundless about these “boundless qualities” is that you’re going beyond your little group. It’s not me, it’s not my group, it’s not my anything. It’s actually taking you step by step from loving myself and having compassion for myself ,to those I easily feel it for, and then so on and so on all the way out to all and everyone who are fellow creations of this ground of being.

Are you of the mind that these teachings are not only helpful to us on a personal level, but in terms of the sociopolitical climate? Meaning that they’re helpful to us because they help us to be better citizens?

Yeah. I work with activists a lot and do some of it myself and we find that we can make a lot of messes trying to fix the world if we don’t start with ourselves. And once we get our understanding of how things really are more in line with how they really are, we make fewer messes once we practice compassion — which is a skill, not just a passing sentiment. Once we build that and the other capacities you enumerated, we’re able to step into the world and be much more effective.

And when we also practice wisdom, as we do with Vipassana, then we’re combining wisdom with compassion. And we’re not just running around like a chicken with its head cut off.

Look at His Holiness the Dalai Lama for example, who has expanded both his capacities for wisdom and compassion to such an extreme extent that I have to pick him as an example.

He’s doing a fantastic amount of good in the world as one person. You know, this one refugee. And it’s because he’s developed those capacities so strongly, I believe.

What kinds of techniques will we learn in this book for doing so ourselves?

Well, as I sort of hinted at, we begin with ourselves. Otherwise it can be an intellectual exercise. So, in the previous book I was teaching Tonglen, which is a compassion practice, for example, and I like to start with something that’s really up for me — something I’m suffering from right now. And, hold myself in compassion and practice it for myself. And then, once I’ve done some of that and really shifted that — because you take away the suffering and replace it with the joy and happiness that is naturally there in the ground of being, you’re bringing that forth — after we’ve practiced with ourselves, then we step it out to people we easily feel compassion for, we already care a lot about. But in order to make it boundless, we don’t wanna stop there.

We wanna step out and out to people we don’t really think about too much. You know: the person who checks us out at the grocery store or you know, people we pass in the hallway at work or something like that. And we think, Well, they wanna be happy and they don’t wanna suffer. So, you know, I bet they’ve suffered from something like this that I’m suffering from, too, at some point.

And, linear time being an illusion, we can practice for them right now. And so we do, and then we step it out further. And once you’ve done this a while, you can actually even do it for people you’ve had difficulties with. But I wouldn’t start out with that right away. That’s a little more challenging. But then you finally step it out to all and everyone, because at some point everybody’s suffered from something similar — maybe an even more extreme version than what you’re suffering from at the moment. So that’s an example with Tonglen, but you do the same thing to make it boundless with all of the boundless qualities.

Now, these practices of these qualities, and of loving-kindness, are probably most strongly associated with Theravada Buddhism and the Insight meditation movement, but they’re common to many Buddhists.

Oh yeah.

How would you characterize the Tibetan Buddhist approach to these ideas?

A couple things. One is, we hear a lot about metta (loving-kindness) in Theravada. There isn’t (in Theravada) the practice of Tonglen as a way to practice compassion and develop your capacity. And sympathetic joy, I don’t, I don’t recall having experienced that in the bit of instruction I’ve had on Theravada meditation. But that’s emphasized too in Tibetan Buddhist practice. And then equanimity is, as you can kind of tell, running throughout all of these boundless qualities, because you can’t make it boundless if you have preference. The point is that you care as deeply for everyone as you did for yourself when you started the practice. So each session, you’re starting with where you can feel it strongly, because indifference isn’t what we’re going for. That’s not equanimity. That’s a near enemy, as a matter of fact, and I talk about that in the book. But we wanna start with that. So we develop a lot of compassion and then move that out so it’s just as strong for everyone.

I wanna say a little bit more about what’s special about the Tibetan Buddhist practice of the brahmaviharas, or the boundless qualities, and that is that all throughout Tibetan Buddhism, you’re doing practices that sort of take our habitual tendencies as human beings and kind of just move them just a little bit so that now they’re actually part of the path to enlightenment instead of you just going around and around in suffering. So, with the brahmaviharas, what you’re doing is, you’re taking our tendency to have internal conversations, where you imagine somebody in front of you and then you have this interaction. So that’s basically what we’re doing with these practices: you imagine somebody in front of you and you do this interaction, it’s just a much more elevated interaction.

That’s beautiful. When we get to Vipassana/Insight in the book, you note that you’d prefer your readers had an established practice of shamatha or calm abiding meditation. Why?

Well, any practice that you do requires that you be able to put your mind on something and have it stay there a while, and that at least it slows down. And that’s really hard for us to do, particularly these days when we’re measuring screen time in nanoseconds. So we have an extra challenge as modern people. We drive in cars that go so many miles per hour, for example. That wasn’t the case when the Buddha and his students were walking step by step from one place to another. It was much, much slower. And I think it was easier then to slow your mind down and have it settle on one of these practices. And so you can accumulate quite a profound experience with that practice when you’re sitting and doing it, but when your mind is racing around like a puppy dog, to get it to do a “down/stay” right away is gonna be kind of hard to do. And as a matter of fact, the puppy’s gonna be frustrated and it’s not gonna work, and they’re gonna hate training sessions. So if you want your mind to love training sessions and be able to do a “down/stay” for a while, then the best is to start with short sessions and skillful practices like shamatha, which means peaceful abiding.

So it’s not frustrated abiding, but peaceful abiding, and your mind can grow in its capacity to be able to do that so it can comfortably sit with practices and you can really develop some strength with them.

To practice shamatha meditation along with Lama Tsomo, keep an ear out for her full appearance on The Lion’s Roar Podcast, coming in November, which will also include her thoughts on finding a Buddhist teacher, and more.

Deepening Wisdom, Deepening Connection is available now from Namchak Publishing.