No, he didn’t become a Buddhist, but in “Person to Person,” Mad Men’s finale, Don Draper certainly came closer than many might have expected he could. Buddhism or no, it made for a memorable meditation-and-pop-culture moment. (Spoiler alert: this post does in fact address the very end of the final episode and some of the details leading up to it.)

His unannounced flight from advertising giant McCann Erickson would take him cross-country to California — just as so many fans expected — and soon enough, we find Don along for the ride to a retreat at what appears to be Esalen Institute in Big Sur. (When the retreat was mentioned onscreen, I thought of my favorite of the Mad Men final-episode theories, and that this retreat might tie into it by giving Don the clarity to enact it. That would turn out to be true.)

By now the telephone is Don’s only lifeline to the people he’s left behind in New York, but checking in, person to person, only brings a sense of everything unraveling. There’s very bad news from back home, and he’s helpless to address it. There’s also bad news right where he is: Don’s drinking is out of control, and he’s this close to hitting bottom. It’s at the retreat in question where all this comes to a head.

The retreat plays just as many of us would think an early-70’s spiritual retreat might, with lots of group talk and touchy-feely exercises and New Age-y slang. Don’s on his own — his ride has left him behind, but he’s paid up to stay through the week — and another call back home, to former protege Peggy, has left him broken and vulnerable. Finding him then, a facilitator brings Don with her into a group session. There, a fellow retreatant named Leonard speaks movingly of his own personal emptiness and aloneness in a way that cuts through to Don. Clearly, Don sees in this man something of himself. He stands and walks over to the man, kneels down, and the two embrace and cry together. Person to person.

It is not what you’d call a typical Don Draper moment. But something more like one — albeit with a different look and feel — is coming.

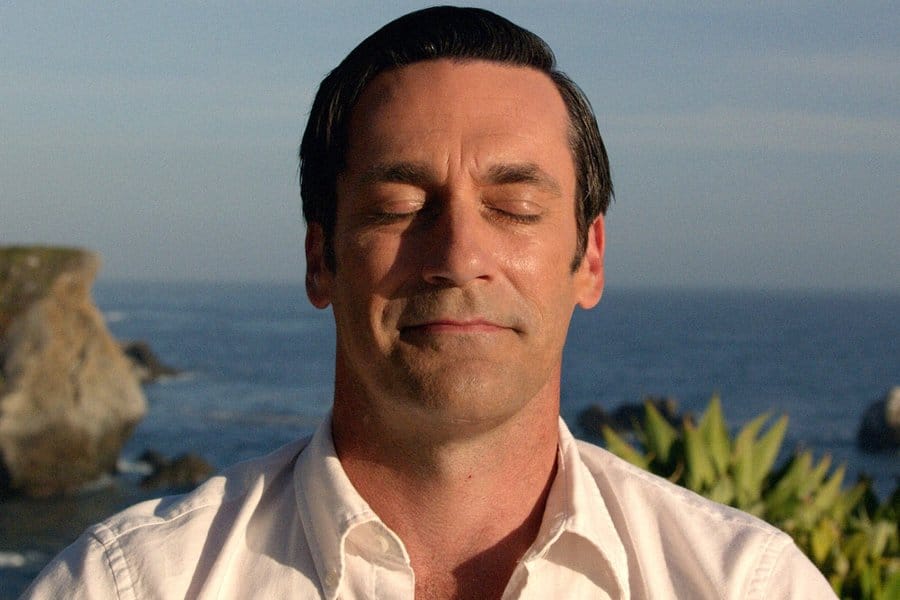

In the last moments of the episode — you can watch the complete sequence here — the show returns to the retreat locale. Don’s stayed on. Outside, we find him — Don Draper, the All-American, Charismatic Ad-Man, the alcoholic, the womanizer, the absentee parent, the mental loner, the creative genius — with a number of other retreatants out on the grass together. Like the rest of them, his legs are crossed in meditation. Like the rest of them, Don is chanting Om…

We hear a ding! And Don smiles. It’s a satisfied smile, as real as a Don Draper smile gets. That ding: is it just a meditation chime, or does it signify something else, too?

We then cut to what we are led to believe is the fruit of Don’s ups, downs, and ultimately, his meditation: The Great American TV Spot, which was in reality the work of McCann Erickson.

Yes: just as the theory mentioned above had posited last week, Mad Men does seem to be telling us that Don Draper was, as far as the show is concerned**, the creator of Coca-Cola’s famous “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” TV spot. The spot was in fact released not soon after the retreat depicted takes place, in 1971.

If that’s the case, what’s going on here? Is Don just one of the first of his kind to cash in on where the new America of his day is heading? Just another insincere master of co-optation, like the ones Thomas Frank decries in The Conquest of Cool, his excellent book on advertising and marketing of the era? Jon Hamm himself seems to think so. As he said on The Rich Eisen Show in January 2017, “I don’t think that Zen moment of understanding of anything really stuck. That leopard is not changing his spots… I think it was more about, he just had a really good idea for a commercial. …He was pretty damaged.”

Is it possible, instead, that has Don truly registered what he’s learned about himself, and about the changing America that Mad Men has so painstakingly recreated for us? Has he re-entered the advertising world with new eyes and restored, deeper values? It’s a lovely thought, not least of all because for Don, his work his been always been his art, and a true source of passion. But then, Don himself has said, “People don’t change.”

Maybe the answer’s somewhere in the middle.** Show creator Matthew Weiner famously worked on The Sopranos, and so knows a thing or two about ambiguity — and how it can make a finale an endless source of debate. So don’t expect to find any “official” answers.

In fact, as Katey Rich wrote for a Vanity Fair recap, “The cut to the famous Coke commercial doesn’t have to mean that Don is responsible for it— it works just as well as a wry comment on the way that genuine spiritual moments, like the one Don seems to be having, can be co-opted as a way to sell syrupy drinks to the masses.”

When we ask ourselves if Don Draper’s found happiness, perhaps we should consider how he himself has described it. There’s this:

“What is happiness? It’s the moment before you need more happiness.”

And also this:

“It’s freedom from fear.”

** In a New York Times article published after this piece was originally posted, Jon Hamm, the actor who played Don Draper, offered his take on the character’s final portrayed moments. Read it here. Then, in a May 20 interview, Weiner confirmed that Draper was to be understood as the author of the Coke ad, adding, “I did hear rumblings of people talking about the ad being corny. It’s a little bit disturbing to me, that cynicism. I’m not saying advertising’s not corny, but I’m saying that the people who find that ad corny, they’re probably experiencing a lot of life that way, and they’re missing out on something. Five years before that, black people and white people couldn’t even be in an ad together! And the idea that someone in an enlightened state might have created something that’s very pure — yeah, there’s soda in there with a good feeling, but that ad to me is the best ad ever made, and it comes from a very good place.” …Lastly, don’t miss John Kenney’s imagining of Draper’s meditative thoughts, via the New Yorker. (Note also that Kenney’s piece credits the Buddha as the speaker of the saying, “Death is certain. And the hour of our death is uncertain. So what is the most important thing?”; while we know he said “Death is certain, life is uncertain” (maranam niyatam, jivitam aniyatam), the phrase as Kenney has rendered, minus the “most important thing” part, it is a Latin phrase, sometimes attributed to Saint Alphonsus Liguori.)