When we first set foot on the spiritual path, many of us believed that spiritual practice was all we needed. Ancient texts spellbound us with stories along the lines of, “They heard the teaching, retired into the forest to meditate, and awoke.” End of story! How simple and easy. But somewhere along the path we ran into a problem—reality. It became glaringly apparent that many classic accounts of spiritual life were extremely idealistic, similar to the Hollywood sagas of boy meets girl, where boy and girl fall in love, ride off into the sunset, and live happily ever after. Anyone in an intimate relationship knows that something has been left out of the story.

In short, spiritual practice turned out to be far more complex and demanding than advertised. True, there were many gifts and graces, and some awe-inspiring glimpses of our spiritual potentials along the way. But covering up these potentials were often layer upon layer of difficult emotions, compulsive conditioning, and countless old wounds, fears, and phobias. And ironically, spiritual practice frequently makes these challenges more painfully obvious.

Clearly we had taken on a big project, and our initial fantasies of doing a few retreats, and thereafter basking in unalloyed bliss, quickly faded as a more realistic appreciation of the path dawned. The enormous challenge of healing and awakening one mind—let alone all minds as per the bodhisattva vow—became dauntingly apparent. Some of us even began to wonder if spiritual practice by itself was always adequate to the task.

Spiritual practice turns out to be far more complex and demanding than advertised. True, there are gifts and graces, but also difficult emotions, compulsive conditioning, and countless old wounds, fears, and phobias.

As a result, many of us who have practiced meditation and undertaken a spiritual path for an extended period have questioned whether there are other methods we can draw upon in trying to optimize our individual and collective healing and awakening—methods that don’t come from the spiritual traditions themselves. And as the number of spiritual, psychological, medical, and other healing practices continues to multiply, this becomes an increasingly perplexing—and ever-more relevant—question. We need a significant and disciplined evaluation of how best to combine dharma and diverse therapeutic disciplines, including the most controversial of all therapies: medication.

In fact, such an evaluation has already begun. It’s in its early stages, but it is indeed underway.

Psychotherapy and Meditation

When Buddhism first came to the West, many teachers and practitioners initially dismissed psychotherapy as superficial, unnecessary, and possibly counterproductive. As time went on, more and more students faced crises or simply felt their spiritual practice was not dealing with deeper problems that were hindering their development. Psychotherapy’s relationship to spiritual practice started to undergo a reevaluation, and the two disciplines began to intermingle a bit more. Among the first to bridge the divide between therapy and spiritual practice was Jack Kornfield, who is both a meditation teacher and psychologist. In 1993, he wrote an article called “Even the Best Meditators Have Old Wounds to Heal: Combining Meditation and Psychotherapy,” which was published in the book Paths Beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision. In it he argued:

For most people, meditation practice doesn’t “do it all.” At best, it’s one important piece of a complex path of opening and awakening… There are many areas of growth (grief and other unfinished business, communication and maturing of relationships, sexuality and intimacy, career and work issues, certain fears and phobias, early wounds, and more) where good Western therapy is on the whole much quicker and more successful than meditation… Does this mean we should trade meditation for psychotherapy? Not at all… What is required is the courage to face the totality of what arises. Only then can we find the deep healing we seek—for ourselves and for our planet.

Controversial in their time, Kornfield’s ideas have now gained wide acceptance. In fact, meditation and psychotherapy are being integrated in many different contexts, as therapy clients and patients are offered meditation and meditators are offered therapy. Research has convinced therapists of the value of meditation for a host of psychological and psychosomatic difficulties. In fact, many therapists and meditation teachers now agree that meditation and psychotherapy can be mutually facilitating. Meditators seem to progress more quickly in therapy, while psychotherapy can improve the effectiveness of their meditation.

In addition, combination therapies that integrate meditation and psychotherapy are proliferating, and often prove more effective than either application alone. The original inspiration was Jon Kabat-Zinn’s widely used “mindfulness-based stress reduction” (MBSR). Originally designed to treat chronic pain, MBSR has since proved helpful with a diverse array of psychological and psychosomatic difficulties. Examples of disorders that have responded well to MBSR range from anxiety, aggression, stress, and eating disorders on the psychological side to asthma, angina, and high blood pressure on the somatic side.

Several recent combinations merge Buddhist mindfulness with specific psychotherapies. These include, for example, “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy” for depression, “mindfulness-based sleep management” for insomnia, and “mindfulness-based relationship therapy” for enhancing relationships. Research affirms the effectiveness of each of these approaches. More broad-based combination treatments—such as transpersonal and integral therapies—incorporate multiple psychological, spiritual, and somatic strategies. In short, the integration of contemplative and conventional therapies is proceeding rapidly, and the results are promising.

Combining meditation and psychotherapy makes sense if we appreciate how they work in complementary ways. For the most part, meditation focuses primarily on developing capacities such as concentration and awareness, whereas psychotherapy focuses primarily on changing the objects of awareness, such as emotions and beliefs. Of course, there are also significant overlaps, but this complementarity suggests why combining both approaches can be very helpful. Meditative qualities can facilitate psychotherapeutic healing of painful patterns, while the psychotherapeutic healing of these painful patterns can reduce their disruption of spiritual practice.

Trying to tough it out and heal oneself with spiritual practice alone may not only prolong unnecessary suffering, but also lead to greater risk of relapse, chronicity, and complications.

What are the practical implications of this conjunction of psychotherapy and spiritual practice? It seems clear that the question of whether meditation and psychotherapy can enhance one another has been decided: many people benefit from combining them, and this has been observed by clinicians and demonstrated by research. When old traumas, pains, and patterns recycle endlessly, or make spiritual practice seem overwhelming and hopeless, the best answer may not be simply the classic one of more practice. Instead, psychotherapy may be called for.

Medication and Meditation

Sometimes neither meditation nor psychotherapy—nor even the combination of the two—is enough. Depression can be so debilitating, anxiety so agitating, and old pains so traumatic that spiritual practice withers and psychotherapy has little effect. Mental approaches alone prove insufficient. And this brings us to one of the most hotly debated topics among spiritual practitioners: the appropriateness of using medication to help with psychological and spiritual difficulties. Two groups have staked out polar positions. We could call them the purists and the pragmatists.

Spiritual purists argue that if mental suffering is fundamentally spiritual and karmic, spiritual practice alone is appropriate to treat it. A standard response to difficulties is therefore “more practice.” Moreover, they are concerned that medication may dull or derail spiritual practice. They worry that if suffering is merely dissolved with a pill, the motivation to practice may dissolve with it. They also worry that medications may reduce or distort awareness, and thereby make practice more difficult. In this view, medications such as antidepressant or antianxiety agents can be novel forms of the “mind-clouding intoxicants” prohibited by the lay precepts to which many Buddhist practitioners adhere. Therefore, taking these modern pharmacological agents is tantamount to violating this precept. Another worry is that potentially valuable spiritual challenges such as the classic “dark night of the soul” may be misdiagnosed as psychopathology, and then be suppressed with drugs rather than explored and mined.

By contrast, pragmatists hold that spiritual practice alone is simply insufficient, or at least not optimal, for healing all mental suffering. While not denying the validity of some purist concerns, pragmatists argue that certain problems and pathologies respond best to other therapies, and one of these therapies can be medication. Stan and Christina Grof—who have written extensively about spiritual emergencies and founded the Spiritual Emergence Network to offer support to people who find themselves in such emergencies—encourage this pragmatic perspective. They certainly agree that some spiritual emergencies are best treated not with medical suppression, but with time-honored spiritual and psychological principles. These principles include providing a supportive relationship with a spiritual guide, reframing (where appropriate) the emergency as a spiritual process and opportunity, and setting positive expectations. However, they also recognize that some emergencies are so overwhelming that they require medical intervention.

As for the idea that there is something inherently unspiritual about taking drugs to modify neurotransmitters such as serotonin, we might consider how John Tarrant Roshi, who is also a Ph.D. psychologist, demystifies the brain’s chemistry. “What is serotonin?” he asks. “It, too, is a piece of the original light. For some people it comes in the form of serotonin; for others in the form of a smile. There is more than one way to move neurotransmitters around—meditation can do it; having someone hug you does it, too.”

Most people with depression, including spiritual practitioners, go untreated.

The purist-pragmatist debate is curiously reminiscent of one that rocked psychiatry decades ago. At that time, the psychiatric world was ruled by psychoanalysts who believed that virtually all psychological problems and pathologies could be traced to earlier psychological causes. They threw up their hands in horror when antidepressants and antipsychotic medications first appeared, claiming that the drugs merely relieved surface symptoms, while leaving the deeper causes untouched. Eventually they changed their minds as pharmacological successes multiplied, and especially when some long-analyzed but little-helped patients responded well to antidepressants, and subsequently sued their psychoanalysts for having withheld medication. It’s not that psychoanalysis is useless, but rather that by itself, it may be insufficient to treat severe psychological disorders. Likewise, meditation and spiritual practice may also be insufficient by themselves to address severe psychological difficulties.

The Hell Realm of Depression

The question of effective treatment is a crucial one, because the cost of inadequately treated mental disorders is extraordinary. For example, major depression ranks as the world’s fourth leading medical cause of disability, and for poorly understood reasons, its frequency and severity seem to be increasing. Yet most people with depression, including those who are spiritual practitioners, go untreated. This is a tragedy, because the suffering and debilitation of major depression can be horrific and heart-rending for all those who are touched by it. Consider the following statements from depression sufferers:

I accidentally tripped over my cocktail table, breaking both of my legs. I want you to know that the pain that I experience from depression is so much worse than the pain associated with my breaking both my legs.

The psychological pain I felt during my depressed periods was horrible and more severe than my current physical pain associated with metastases in my bones from cancer.

Hearing these expressions of pain coming from the depths of people’s being reminds us that depression has been regarded as a spiritual crisis in some traditions, despite that fact that classical Buddhism makes little mention of it. For example, the noted Jewish Kabbalist, Aryeh Kaplan, was very explicit: “There is nothing that can prevent enlightenment more than depression, even for those who are worthy.”

Most people today know someone who has been affected by depression, and therefore understand how severe and disabling depressive suffering can be. And for some time now, we have been hearing accounts about the relief that antidepressants can offer to those who have been struck with it. Buddhist practitioner Sheva Carr long resisted taking medication, but after doing so, wrote movingly:

Do you know what it is like

to be so sensitive

that the air makes your eyes

sore and so does sleep?….

To be so sensitive

that food forges flaming

fireworks in your gut?….

What is it like to go on

antidepressant medication?….

It is what it is like to be drowning daily

and then suddenly find yourself floating

face up to the sun.

In spite of a growing body of research evidence indicating the effectiveness of medication, and anecdotal accounts of its benefits for meditators, there has been much debate in spiritual circles about the use of medication. What has been lacking, however, is actual research and data on spiritual practitioners themselves. So we and others have begun to undertake such research, and early findings indicate that when it comes to the use of medication by meditators, the evidence is lining up on the side of pragmatism.

Brain and Mind

Let’s look first at the relationship between mental states and brain states. We all know that changing the state of the brain—such as by hunger, a cup of coffee, or a tranquilizer—can have dramatic effects on mental states. What new technologies such as brain scans reveal is that the causal relationship can run in the other direction: mental states also affect brain states. A wide array of stimuli and situations—from exercise and out-of-the-ordinary experiences to meditation and psychotherapy—can actually alter both the structure and function of the brain. (For an excellent summary of what researchers have been learning about neuroplasticity, meaning how brain structure and function is able to be modified, see the book Train Your Mind: Change Your Brain, by Sharon Begley.)

It is therefore not surprising that meditation and psychotherapy can improve some neural functions, and sometimes partly heal the chemistry and even structure of the brain. Consequently, we can certainly expect that some brain–mind dysfunctions will be healed, or at least ameliorated, by spiritual and psychological interventions.

But other dysfunctions may prove recalcitrant. Major chronic disorders—whether the result of faulty genes, horrendous child rearing, or long-term stress—may be so severe and so indelibly stamped into neural chemistry and architecture that almost no amount of meditation or psychotherapy will fully reverse or override them. In such cases the most strategic way to redress both symptoms and the underlying neural pathology may be by direct neural interventions, which most commonly take the form of rebalancing neural chemistry via medication.

Again, this is not to say that spiritual practice or psychotherapy won’t help, but rather that, by themselves, they may be insufficient. Even very long-term practice may be insufficient. In fact, we have seen and consulted with not only practitioners, but also several teachers whose long, dedicated practice was simply not enough to fully override genetic forces and major traumas, and who benefited from medication. Optimal healing may require multiple therapies, one of which is pharmacotherapy.

This is easy to say, but it can still be a hard decision for spiritual practitioners wrestling with the question of whether to begin taking medications, most commonly, antidepressants. This is where research on how spiritual practitioners have fared when taking medication could offer helpful information to those trying to make this difficult decision, particularly if they face the pressure of the purist point of view.

Buddhist Practitioners Who Took Antidepressants

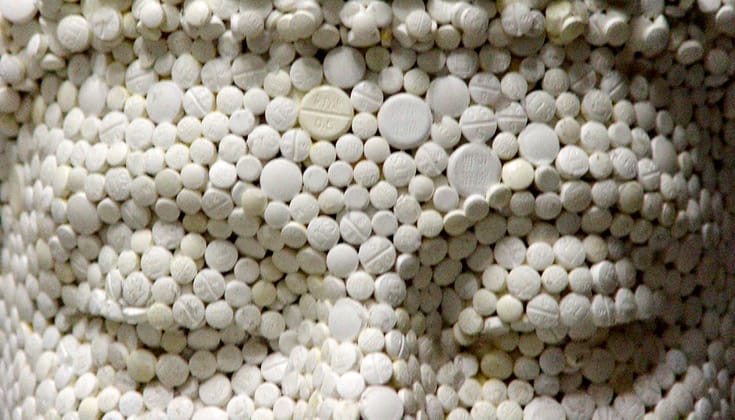

Our team of researchers, all physicians and long-term meditators, investigated a group of nineteen Buddhist practitioners (thirteen women and six men) diagnosed with major depression. These practitioners had all been doing meditation, mainly vipassana, for at least three years, had participated in two or more weeklong retreats, and had used antidepressants in the last two years. By far the most commonly used medications were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—such as Prozac, Zoloft, and Celexa—which as the name indicates specifically inhibit the reuptake of the mood-regulating neurotransmitter serotonin.

We asked these practitioners for detailed reports on their experiences while taking antidepressants, both in daily life and on retreat. We wanted to find out not only if the antidepressants seemed to help, but exactly how they helped, and what effects they had on mind, meditation, and daily life.

The effects proved powerful and positive. Most of our subjects reported that antidepressants helped them with multiple emotional, motivational, and cognitive functions. Emotional changes were consistent with an antidepressant effect. The painful emotions of anger and sadness decreased significantly, but fear showed a smaller response. The positive emotions of happiness, joy, love, and compassion all increased, as did self-esteem.

Motivation underwent an intriguing shift. Depression is often accompanied by a dispirited lack of motivation and interest, so it is significant that our subjects felt more motivated. Yet at the same time they reported that attachments or craving actually diminished. Clearly, they were reporting a motivational shift in a healthy direction. Subjects also felt calmer and that their awareness was clearer. One would expect this kind of result, given that the subjects were no longer wrestling with intense, painful emotions.

Two benefits we had anticipated were not clearly displayed by the participants. During depressive episodes, people often complain of low energy and poor concentration. Consequently, we expected that successful antidepressant treatment would improve energy and concentration. However, while there was a trend in this direction, it did not reach statistically significant levels.

The largest effect of all was a dramatic increase in equanimity. Equanimity is the capacity to experience provocative stimuli fully and nondefensively, without psychological disturbance. It is highly valued across contemplative disciplines, and has been described as “divine apathea” by the Christian Desert Fathers, “euthymia” by Stoics, “dispassion” by yogis, and “serenity” by Hassidic Jews. In Buddhism, equanimity is one of the seven factors of enlightenment (seven mental qualities that are particularly vital for spiritual maturation) and the last of the four immeasurables, or four divine abodes, of loving kindness, compassion, empathic joy, and equanimity.

What We Have Learned?

What do these findings suggest? Clearly, the large majority of these meditators felt that they, and their spiritual practice, benefited significantly from taking antidepressants. The changes they described bear this out. In fact, whether looked at from either a classical contemplative or a contemporary psychological perspective, the multiple benefits they describe suggest greater psychological and spiritual well-being.

Several subjects reported that the antidepressants enabled them to recommence or significantly improve their meditation and spiritual practice. In addition, two subjects spontaneously reported that antidepressants gave them a lift that they were subsequently able to maintain with meditation alone. This observation that meditation may maintain gains initially obtained with medication is particularly important because it is now painfully apparent that major depression can be a long-term, relapsing condition, especially if left untreated. In fact, the longer major depression goes untreated, the more likely it is to become chronic, to relapse, and to become resistant to treatment. Early effective treatment and relapse prevention are crucial.

But how to prevent relapses is the challenge. Most physicians—and therefore their patients—now rely on long-term pharmacotherapy alone, even though once medication has alleviated the initial crisis, psychotherapy is sometimes more effective in preventing relapse. A similar pattern is emerging for other psychological disorders, such as panic disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Here, too, initial medication can be helpful or even essential, but psychotherapy is sometimes more effective for maintenance. Certainly some people continue to require medication to prevent relapse. But psychotherapy helps others to maintain their health after eventually stopping the medication.

It seems likely, then, that meditation and other spiritual practice—especially daily, long-term practice—might also help to prevent relapse and maintain health. In fact, the combination of meditation and cognitive therapy in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has already proven particularly helpful in preventing relapse back into depression.

Limitations of Antidepressants

Of course, antidepressants are not panaceas. They do not work well for everyone and, like all drugs, can have side effects. Unfortunately, they are often the only treatment offered by some physicians, and the only one medical insurance will pay for, even though they work best when carefully titrated by a psychiatrist and combined with other approaches.

An optimal combination might include antidepressants, psychotherapy, spiritual practice, and a healthy lifestyle. Such a lifestyle would certainly incorporate exercise, which can be very helpful for anxiety, depression, and many other psychological ills, especially those that are stress-related. Other essential lifestyle ingredients include social and spiritual support, time spent in nature, body work, and a good diet. In fact, dietary fish-oil supplements can be very helpful with depression, and possibly a wide range of other mental (and physical) health disorders as well.

Buddhist psychology regards happiness and joy as healthy, beneficial, spiritual qualities, and discourages subjecting oneself to unnecessary pain as a spiritual path.

Are there “spiritual side effects” or complications from antidepressant use? Our study did not detect any. However, this was a small study, and larger ones may well detect subtle spiritual costs, and perhaps more subtle benefits as well. Some practitioners, not in our study, complained of problems that could be termed spiritual side effects, particularly of being distanced from their feelings. In fact, one of us, Roger Walsh, discovered something similar when he was given the SSRI Zoloft to treat a gastric disorder (antidepressants have many uses in addition to treating depression). Though no side effects emerged while doing vipassana, during a metta retreat he found that the drug inhibited the powerful positive emotions of happiness, joy, and love usually elicited by this practice. In fact, his observation provided the original motivation for doing our research. There may well be other subtle spiritual and psychological side effects from antidepressants (and other medications) that have yet to be identified.

This simply confirms the classic wisdom that all treatments—medical, psychological, and spiritual—can have side effects and unexpected complications. There are no free therapeutic lunches; all treatment decisions involve weighing costs and benefits. However, it is crucial to realize that it can be far more costly not to treat a disorder than to treat it.

Our small study, combined with other research, clinical observation, and patient reports, seems to indicate that many spiritual practitioners suffering from depression can benefit both spiritually and psychologically from the appropriate use of antidepressants. More generally, spiritual practitioners suffering from a variety of psychological disorders may benefit from judicious use of multiple therapies, including psychotherapy and medication. Trying to tough it out and heal oneself with spiritual practice alone may not only prolong unnecessary suffering, but also lead to greater risk of relapse, chronicity, and complications.

Being willing to face the unavoidable pains of life is often a sign of courage and wisdom. Nonetheless, being unwilling to use effective therapies to relieve unnecessary pains may be a sign of misunderstanding, and of a spiritual superego run amuck. After all, Buddhist psychology regards happiness and joy as healthy, beneficial, spiritual qualities, and discourages subjecting oneself to unnecessary pain as a spiritual path.

What we and our troubled world need is to carefully assess and optimally use the unprecedented array of therapies now available to us. Only such an open-minded, multipronged approach can hope to address the many sources of suffering, and thereby optimize healing and awakening for us and our world.

The authors would like to thank the practitioners who volunteered to be subjects for the research described here.