What does Buddhism add to conventional Western conceptions about money? St. Paul the Apostle, one of the first proponents of Christianity, taught that love of money is the root of all evil, emphasizing that our greed and attachment to money is what makes it such a problem—for those who have it, at least. The New Testament also warns us not to “lay up for ourselves treasures on earth” (Matthew 6:19-21), for how do we profit if we gain the world but lose our souls in the process? And long before those biblical verses were written, the Greek story of Midas and his golden touch gave us the classic metaphor for what happens when money—pure means—becomes an end in itself.

Today money serves at least three functions. For better or worse, it is our indispensable medium of exchange. Worthless in itself—coins and bills can’t be eaten or shelter us when it rains—it is at the same time more valuable than anything else. Because it is how we agree to define value, money can transform into almost anything.

Second, money functions as our storehouse of value. Before money became widely used, one’s wealth was measured in cows, full granaries and children, but they are vulnerable to rats, fire and disease. The advantage of gold and silver—and now bank accounts—is that they are incorruptible and therefore, in principle, immortal. This is quite attractive in a world haunted by impermanence and death. Capitalism added the final fillip: invest your surplus and watch it grow! And is there anything wrong with that?

Well, maybe. The anatta—“no self”—teaching gives Buddhism a special perspective on dukkha, suffering, that also implies a special take on our problem with money. The problem isn’t just that I will get sick, grow old and die. My “emptiness” means that I feel something is wrong with me right now. I experience this hole at the core of my being as a sense of lack, and in response I become preoccupied with projects that I think can make me feel more “real.” Christianity gave us an explanation for this lack and teaches a solution, but many of us don’t believe in sin anymore. So what is wrong with us? The most popular explanation in the West today is that we don’t have enough money. That’s our contemporary “original sin.”

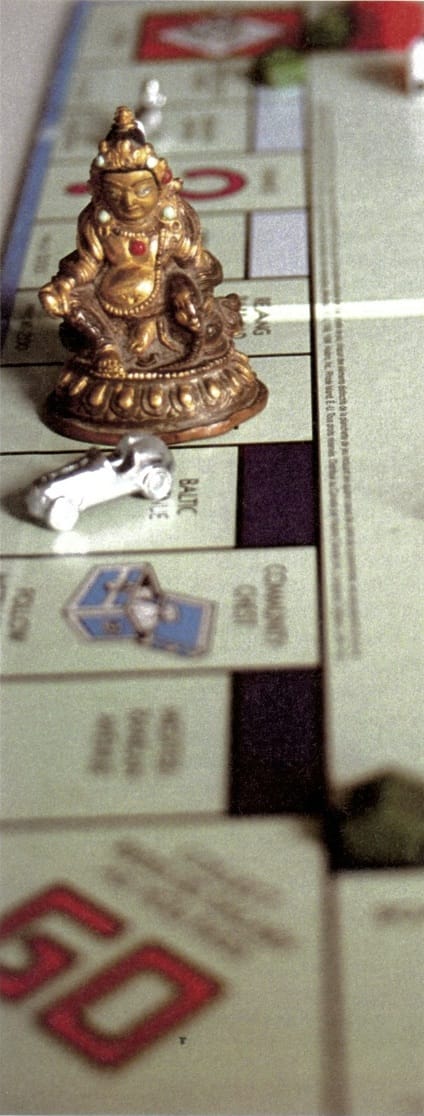

Beyond its usefulness as a medium of exchange and a storehouse of value, money’s third function is as our most important “reality symbol.” Money has become our favorite way to try to accumulate a feeling of being, to gain a solid identity, and to cope with the gnawing intuition that we do not really exist. Suspecting that our sense of self is groundless, we used to visit temples and churches to ground ourselves. Now we struggle to ground ourselves financially.

The karmic rebound? The more we value money, the more we find it used—and the more we use it ourselves—to evaluate us. We end up being manipulated by the symbol we take so seriously. In this sense, the problem is not that we are too materialistic but that we are not materialistic enough, because we are too preoccupied with the symbolism. I become infatuated not so much with the things money can buy, as with their power and status—not with the usefulness of an expensive car but with what owning a Lexus says about me: “I am the kind of guy who owns a Lexus, a trophy wife, a condo on Maui…”

The difficulty with this, from a Buddhist perspective, is that we are trying to resolve a spiritual problem—our “emptiness”—by identifying with something outside ourselves, something that can never confer the sense of reality we crave. We work hard to acquire a big bank account and all the things that society tells us will make us happy, and then we do not understand why they do not make us happy, why they do not resolve our sense that something is lacking. The reason must be that we don’t have enough yet.

Perhaps Mahayana Buddhism gives us the best metaphor to understand money: shunyata, the emptiness that characterizes all phenomena. Nagarjuna warned that there is no such thing as shunyata: it is a way to describe the interdependence of things, how nothing self-exists because everything is part of everything else. But if we misunderstand the concept and cling to shunyata, the cure becomes worse than the disease. Money—also nothing in itself, also nothing more than a socially agreed-upon symbol—remains indispensable today. But woe to those who grab this snake at the wrong end: all form is empty, yet there is no emptiness apart from form.

Another way to put it is that money is not a thing but a process, an energy that is not really mine or yours. Those who understand that it is an empty, formless symbol can use it wisely and compassionately to reduce the world’s suffering. Those who use it to become more “real” end up being used by it, their alienated sense of self haunted by a promise money never fulfils.