Cliff Saron lives and breathes contemplative science. Tall with a short beard, he runs the lab that bears his name in the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, where his research interests range from how meditation might reduce the impact of stress on attention to the contemplative qualities of music, which he explores in partnership with his wife, Barbara Bogatin, a cellist with the San Francisco Symphony.

Saron’s career stretches back to 1975, when there was no real field called “contemplative science.” Fresh out of Harvard, he was a research assistant in a lab measuring brain responses to stimuli. Cambridge was a hotbed of interest in meditation, and friends and colleagues included future luminaries in contemplative science, such as Richard Davidson and Dan Goleman.

In those days, studying meditation was regarded by mainstream science with suspicion, to say the least. More than one aspiring researcher was told to stay away from the topic because it was a career killer. But scientists and would-be scientists—including cognitive scientists and psychologists—were starting to meditate, just like other young people in the sixties and seventies. Their scientific interests—in how the mind and brain worked, how we construct a world, what constrains us, what liberates us—were intertwined with their own explorations of meditation practice.

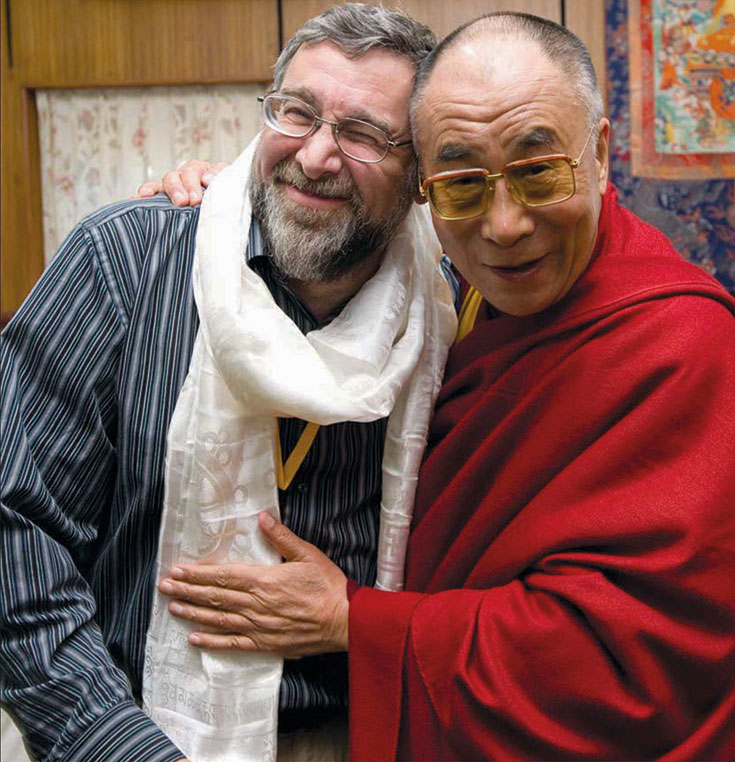

The Dalai Lama played a key role in sparking the dialogue between science and contemplative practice. He was coming to believe that as Buddhism grew to be a more potent force in the world, it needed to engage with science. As the early scientific explorers of meditation encountered the Dalai Lama and other Buddhist masters, an extraordinary series of dialogues began. These gave birth to the Mind & Life Institute, which cognitive scientist Francisco Varela and entrepreneur Adam Engle launched in 1987. According to the institute, the founders “understood that science was the dominant framework for investigating the nature of reality and the modern source for knowledge that could help improve life for people and the planet. And they wondered: what impact could be achieved through combining scientific inquiry with the transformative power of contemplative wisdom?”

To many it seemed a little crazy. These were two very different domains, and never the twain shall meet. One, spiritual practice, was an inner, subjective experience, based on revered spiritual authority. The other, science, was purely objective, based on measurable, empirical evidence alone. But, as Cliff Saron says, there’s more similarity between the two than we might think.

“Doing good science,” he says, “is a contemplative path, as my mentor and friend Francisco Varela pointed out. You have to admit you don’t know what you’re doing, because no one has done it before, so you let your findings reshape your thinking.” In Saron’s view, scientists make creative leaps into the unknown, and it’s the same quality of not knowing, of learning as you go by direct experience, that is essential to contemplative practice, beginning with the Buddha’s instruction to “Be a lamp for yourself.”

More than the effort to “prove that meditation works,” it is this inquiring quality, in Saron’s view, that accounts for the fact that almost four decades after the early meetings that gave birth to contemplative science, it is alive, well, and growing, with laboratories across the world studying the effects of contemplative practice on attention, working memory, anxiety, compassion, equanimity, pain, and countless other conditions.

As a testament to the depth and breadth of the work in this arena, you can listen to more than fifty hours of interviews on the Mind & Life podcast, most with researchers who were pioneers in contemplative science. This first generation of contemplative scientists are mostly in the late career stage now, but they have been building labs and mentoring researchers who will carry contemplative science forward. To get a first-hand feel for what these researchers work on and what motivates them, I talked to a few of them working at Cliff Saron’s lab at UC Davis and Amisha Jha’s lab at the University of Miami.

Brandon King had a BA in Psychology and was doing emotions research using the Facial Action Coding System popularized by the pioneering psychologist Paul Ekman when he was recruited to work on the Shamatha Project.

The Shamatha Project is a groundbreaking study of the long-term effects of meditation practice on participants who did three months of intensive practice at a Buddhist center in Colorado. Saron is the principal investigator, and participants are guided in their meditation practice by contemplative director and Buddhist teacher B. Alan Wallace.

Brandon King first met Saron in person when the scientist picked him up at the airport to drive him to the remote retreat in the Rockies. That was over fifteen years ago, and King has worked continuously in contemplative science research ever since. Today he’s a postdoctoral researcher at The Saron Lab at UC Davis.

King earned his PhD with a dissertation on Shamatha Project research. Specifically, he looked at meditators’ responses to suffering by measuring their heart rate and cardiovascular response when exposed to certain stimuli. A common question in such research is how salient—i.e., impactful—the stimulus really is to the perceiver. King employed a traditional methodology that exposes subjects to a set of threat pictures—guns, snakes, and the like. They are highly salient. But what about pictures of people suffering? Are they salient?

Photo by Clifford Saron

As King told me, “Threats arouse our instinct to protect ourselves, the fight-or-flight response, whereas images of others suffering would generally not be as salient. If you’re going to become more compassionate as a function of meditation training, would the suffering of others become more salient to you, thereby provoking a response that measures closer to your response to a direct threat?”

Comparing responses before and after the retreat, King reported—in a paper called “Cultivating Concern for Others: Meditation Training and Motivated Engagement with Human Suffering” in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General—that the gap between participants’ responses to pictures representing threats to themselves and to pictures representing the suffering of others had narrowed. This led to the inference that practitioners’ attention had been altered to notice others’ suffering more, presumably a precursor to concern for their welfare.

Along with others at the lab, King has continued to do research in this vein, comparing the effects of different types of contemplative training on responses to others’ suffering. They’ve also used this project as an opportunity to innovate, curating a wider variety of scenes of suffering and employing eye-tracking as a further measure of response.

This new work is known as the Pathways Project, because at The Saron Lab there is a strong interest in how different kinds or paths of training work for different types of people. King in particular would love to learn more about how people make choices about their meditation practice. How do they decide how much meditation to do, what kind to practice, at what level of intensity, and how to integrate it with daily life? Whereas religion often assumes everyone is the same, science reveals tremendous variability. One size does not fit all.

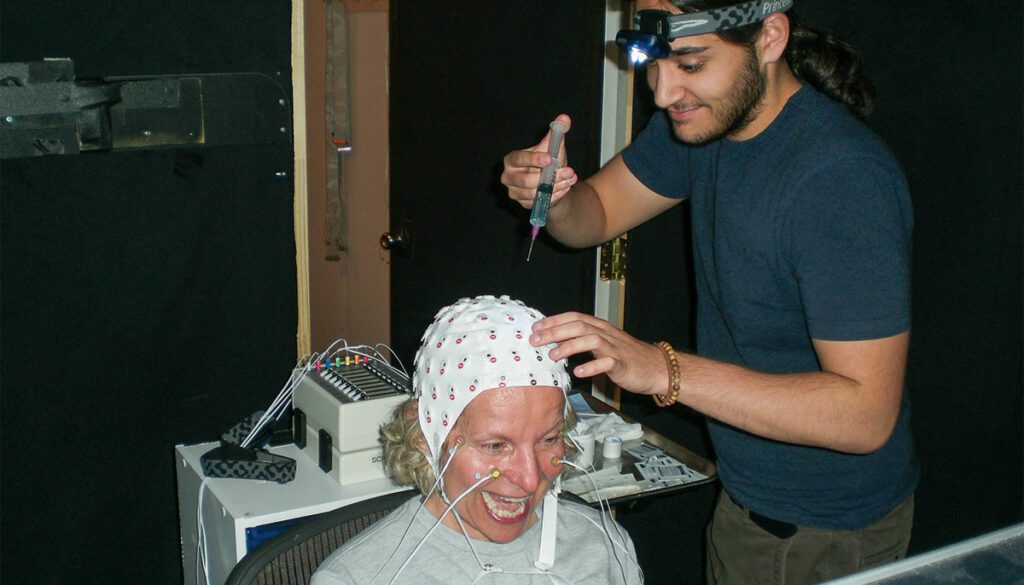

A monk in robes with electrodes attached to his head—that’s the iconic image of the scientific study of meditators, as depicted on the cover of National Geographic in March 2005. But for Quinn Conklin, that image doesn’t fit her brand of research.

With a degree in biology and an interest in meditation and yoga, Conklin didn’t want to pursue the neuroscience approach, which involves a tremendous amount of computer science. There are plenty of other ways to study the effects of contemplative practice—and conversely, the effects of stress—besides electrical activity (using EEG) or blood flow to different regions of the brain (using fMRI).

Blood samples, for example, can measure biomarkers like telomere length, which is affected by chronic stress. Telomeres are repetitive sequences of DNA that protect our genetic material by flanking the ends of our chromosomes. They shorten incrementally with age, but how fast they shorten can be affected by lifestyle.

Conklin was drawn to The Saron Lab because of its work on telomerase, which is the enzyme that maintains the length of telomeres. This work was in keeping with her evolving interest in the effects of adversity and trauma on our biology and how contemplative practices might facilitate healing.

The Shamatha Project had shown that telomerase levels might be affected by meditation practice, so the lab included telomere research in a subsequent study of monthlong meditators at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in northern California. That work became a key part of Conklin’s dissertation, in which she explores data from the monthlong retreat showing an increase in participants’ telomere length.

Since that time, Conklin has gone on to be one of the principal investigators in the Contemplative Coping During Covid-19 project. This study looked at the experience of approximately 350 meditators during the pandemic, including measuring telomere shortening in relation to stressors people experienced over the yearlong study period, trying to determine how much the meditators drew on contemplative practices to cope with the Covid-related stressors, and whether contemplative practice related to better mental health and biological outcomes. Data was collected between June of 2020 and February of 2022, and as of publication is currently being analyzed.

Conklin’s personal practice interacts with her research in interesting ways. “I have an ongoing meditation practice,” she tells me. “I’m also a scientist investigating practice. Yet when I hear Buddhist teachers using the science as a reason or motivation to practice, I find that challenging to digest, because I know how early a lot of the science is.

“Yes, there is a lot of research that supports these practices being beneficial for well-being, but as a practitioner I don’t find it all that compelling compared to seeing how it shows up and manifests in my own life. Meditation does not lend itself to being studied easily. The word itself contains a lot of different meanings. My ongoing interest, though, is to learn more about how these practices work, and what we might be able to do better to foster more well-being for more people.”

For Tony Zanesco, it started early one morning as he was sitting in a café reading a book on Buddhism. He was an undergraduate at UC Davis studying psychology and philosophy, and he had been testing the waters with meditation practice. Who should walk by but Cliff Saron, who spotted the book and struck up a conversation. That led to a visit to the Center for Mind and Brain, which was in its early years, and eventually to work on the Shamatha Project.

Zanesco found himself living in the basement of Shambhala Mountain Center, now called Drala Mountain Center, which was home to the project. Above his basement room participants meditated, and periodically they would come down to his subterranean lair to attach themselves to machines that measured brain activity as they performed certain tasks. Zen masters bring meditators into small rooms and ask them tricky questions to assess whether their practice is working. Scientific researchers also invite meditators into small rooms, searching for different kinds of evidence.

Zanesco has fond memories of the Shamatha Project. “It’s rare to have the opportunity to take part in a large, intensive study measuring meditators’ brain activity,” he says. “While the meditators were on retreat, we were on a work retreat below them, operating a full-scale laboratory with two tons of equipment, working twelve hours a day, and also following some of the protocols of the retreat, including maintaining silence in the hallways and restrooms. I saw the value of contemplative practice, and I caught the bug for neuroscience research.”

Zanesco became one of The Saron Lab’s first graduate students. Then, after earning his PhD in 2017, he moved to another of the country’s leading contemplative research centers, the Jha Lab at the University of Miami, under the direction of Amishi Jha.

The Jha Lab is best known for its work on sustained attention, working memory, and resilience. Among the people it studies are military personnel and first responders. Zanesco had been doing work on mind-wandering at The Saron Lab and has continued to do so in his current position. Mind-wandering may seem relatively harmless, maybe even beneficial in some contexts, but when your mind goes “off-task,” if you’re a pilot or a firefighter, it could be fatal. Even in less life-and-death circumstances, our mind can wander off the rails and into spirals of ruminative anxiety.

The question at the heart of Zanesco’s research is how trainable cognitive processes—such as attention—are, and what kind of training and in what dosages can make a difference. A standard method for measuring sustained attention asks participants to spend about thirty minutes looking at a screen that repeatedly presents lines with minute differences in length. Over time our “vigilance” decreases: attention tends to lag, and we get less and less good at the task of distinguishing the lines.

Zanesco doesn’t condemn daydreaming per se and acknowledges that it could be the source of some creativity. Nevertheless, he says, “There are clearly times when mind-wandering takes us off a task that has real consequences. Do we have some cognitive control, or are we unable to stop ourselves from daydreaming, even when the need arises? Agency over our cognitive process seems to be a facet of mind-training.”

In his work in both the Shamatha Project and at the Jha Lab, results have indicated decreased mind-wandering and higher sustained attention as a result of mindfulness training. As usual, though, the results are preliminary.

“These are simply very difficult phenomena to study,” he says. “Humans are messy. And yet, the bar for the rigor of psychological research and the

quality of evidence is getting higher. We need to understand more at a basic level how these sophisticated cognitive processes work and how we can train them. What kind of practices work and how do they work?”

Alea Skwara was deeply attuned to suffering from an early age. Even as a little child, she remembers, she would “fall down the rabbit hole of other people’s suffering.” The question of how to relieve suffering in the world was

continually percolating in her mind. That, of course, is the central question and goal of Buddhism, and after college she began practice in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

Skwara went to work in the health care field, but soon became disillusioned by the way the health care system was driven by insurers and cost cutting. She was dating other meditators, and while practice opened her up and made her more emotionally available and present, the opposite seemed to be happening to some of the young men she was meeting. They seemed focused on spiritual ambition, and their practice seemed to be making them tighter and less tolerant. She wondered how people doing the same practices could have such different outcomes.

These questions led her to a master’s degree in psychology and neuroscience from NYU, a two-year stint as a lab manager at Harvard, and finally, to Cliff Saron’s PhD program at UC Davis.

In The Saron Lab she began by analyzing the brain activity data from the compassion training in the Shamatha Project to see if there was evidence that with practice, we can cultivate compassion for people we’re not naturally inclined to feel compassionate toward. The EEG data did not provide that evidence, which led to a deeper inquiry about the way compassion training is structured and the challenges of doing meditation research.

Skwara describes it like this: “There is a desire to show that practices are legitimate, but as a meditator who practices science, I have to apply equanimity and beginner’s mind to my research as well—not be attached to the outcome, not be attached to proving something—and just try to understand. In meditation, I’m familiarizing myself with my own mind. Here I’m familiarizing myself with phenomena that hopefully teaches us something that can be of service to the world. I think there is value, both in the practical application of meditation research, and in building a deeper understanding of the mind, that leads to us to become a more compassionate species.

“It’s one thing if we’re taught that humans always have divisions, and we fight wars because that’s how our brains are structured. It’s another if we’re taught humans have an immense capacity to expand their care for others, and here’s how our brains do that. That matters.”

The researchers I spoke with are young, highly trained—usually in both research and contemplative practice—and dedicated to the cause of advancing our knowledge of how cognitive mechanisms work and how they can be trained to bring about greater well-being, healing, and health. They believe in the value of rigorous study of contemplative practice. Without question, this work has come a long way from the times when earlier researchers were counseled to stay away from meditation research because it was a career killer.

Today, there is greater acceptance of the validity of contemplative practice and greater mainstream interest in seeing it studied, just as every other kind of intervention to improve human well-being is subject to study in our modern world. But a new generation of researchers is working to bring the power of contemplative practice even further into the mainstream. They do not need to concern themselves with legitimizing this field of study—that’s already happened—nor are they obsessed with trying to prove the practices work. They want to advance learning for the greater good.

As Cliff Saron made clear to me in our conversations, science relies on an inquiring, relentlessly curious mind. In that sense, science and contemplative practice are bedfellows, and science can, in some contexts, even be said to be a form of contemplation. Repeated scientific research into how our world is put together reveals to us over and over again the impermanence and interconnectedness that are at the heart of spirituality—how we are connected to everything within and all around.

The poet and one-time Buddhist monastic Jane Hirshfield believes that science and poetry and spirituality are not as far apart as we think. Not-knowing is central to them all. As she said at the Nobel Prize Summit in May 2023, “None of us ends at our own skin. This is a truth of both poetry and science.” It is a truth of both Buddhism and science as well.

This article is from the March 2024 issue of Lion’s Roar magazine.