Andrea Miller profiles New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care, a hospice service center with Buddhist chaplaincy.

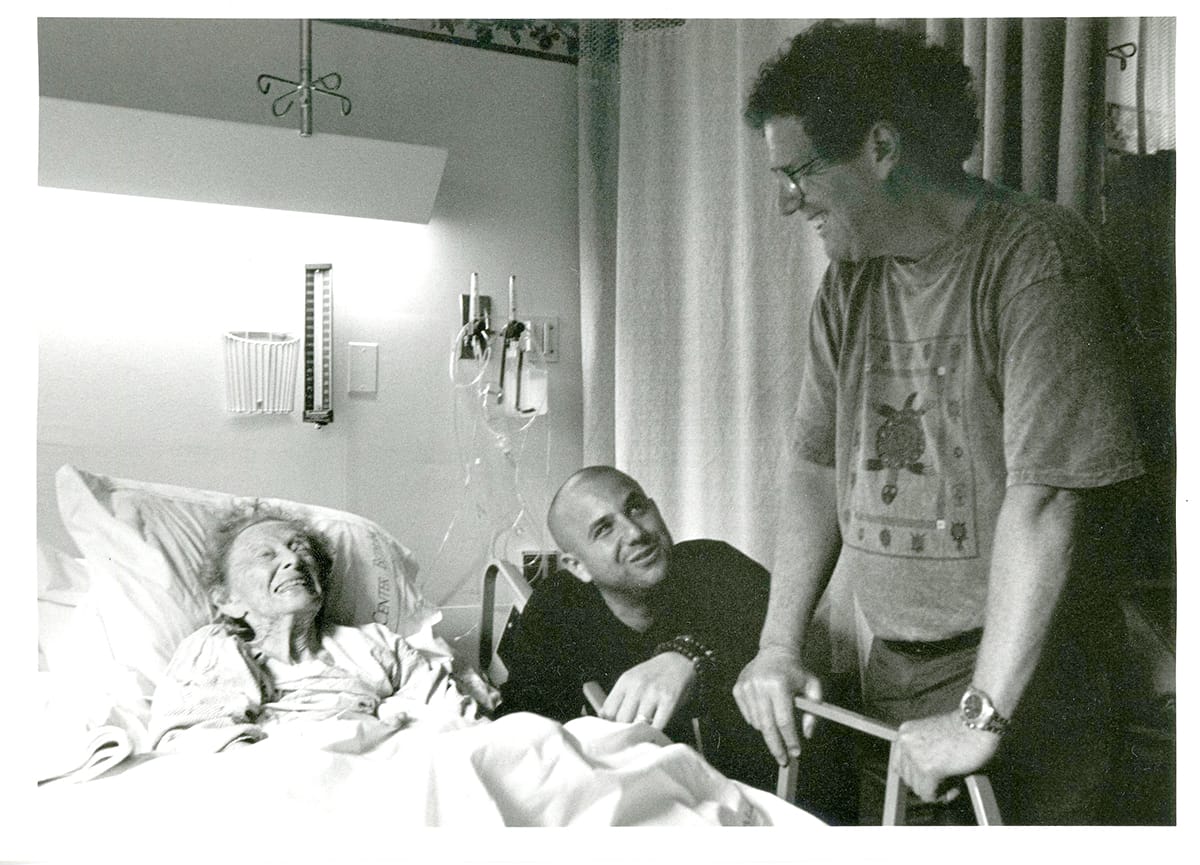

Ellison, who at that time had been practicing Zen for fourteen years, says his grandmother suggested that he look into doing chaplaincy work himself. That was eight years ago. Today, Ellison is the codirector of the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care (NYZCCC). Established by him and Robert Chodo Campbell in 2006 in the heart of Manhattan, the center offers two principal programs. The first—Foundations in Buddhist Contemplative Care Training—is designed to teach caregivers and those interested in caregiving how to integrate contemplative practices into their work with patients. The second—Clinical Pastoral Education—is the only Buddhist program of its kind in the United States that is fully accredited by the Association for Clinical Pastoral Education. Trudi Jinpu Hirsch, who is on the core faculty of NYZCCC’s chaplaincy training program, explains that the foundation program is a prerequisite for the clinical pastoral education training. She says it “is a way of seeing if people are actually—to use a Christian word—called to this ministry.”

Hirsch began training people in contemplative care because she wanted to bring more Buddhists into chaplaincy, a field dominated by Christians. “The first noble truth is that there is suffering,” she says. “Buddhists sit with that in meditation for long periods but we’re not necessarily standing up and doing anything with it.” Contemplative caregiving is a way to practice off the cushion. However, students of the New York center’s program are not required to be Buddhist. They come from a number of religious traditions—Catholics, a rabbi, and an Episcopal priest have all trained there.

“We’re not training people to serve Buddhists,” Ellison says. “We’re training people to be intimate with anybody.” So if patients want to pray, Buddhist chaplains pray with them, and if patients want to talk, the chaplains talk with them.

How, then, does Zen center’s approach differ from traditional care? Roshi Enkyo O’Hara, the NYZCCC’s guiding spiritual teacher, explains: “We train people to really be present to what’s arising in the room. What is the body language? What are all the things that are going on? And in that mindful way, which we learn after years of meditation, contemplative caregivers absorb the whole room in an instant and are able to find that little chink that allows a relationship to arise—just that one hair’s breath that allows something to grow.”

Providing contemplative care is largely about listening, Ellison says. “In the training, we say people are always telling their whole story.” Hospital food is typically terrible, but why does one patient talk about it and another patient talks about something totally different? Ellison says the patient who’s talking about food may be saying that he doesn’t know how to nourish himself in hospital, whereas the patient who’s talking about her favorite baseball player getting up to bat is perhaps talking about her spirituality and how she relates to events in her life. Really listening, says Ellison, makes everything come alive and makes you more fully yourself. “To me,” he says, “that’s the beauty of Buddhist practice as well.” Through both listening and meditation, he notes, you realize that you’re not separate from anyone else, and that the person in the sick bed will be you someday.

Another key is self-care for the caregiver, but that’s not emphasized in traditional caregiving. Meditation practice helps people to slow down, and students in the program are encouraged to sit regularly. Ellison thinks back to his grandmother’s chaplain. “That person had too many jobs,” he says, “so he would come into the hospice and make his rounds as quickly as he could. That’s a teaching in itself—if you find yourself racing, stop. This reminds me of the story of Angulimala and the Buddha. Angulimala is trying to chase the Buddha and says, ‘Why won’t you stop?’ The Buddha says, ‘I stopped a long time ago. How about you, Angulimala?’ That stopped Angulimala in his tracks. It was the moment when he finally asked, ‘Why am I racing around?’”

Students gain clinical experience through ten-month placements with the center’s clinical partners in New York, including the Visiting Nurse Service of New York’s Hospice and the Beth Israel Medical Center, one of the city’s premier hospitals. “Not a week goes by that everyone, including the teachers, isn’t actually in a hospital room or at a bedside,” O’Hara says.

Ellison points out that each hospital unit is like a different world. “Patients on the cardiac floor are completely different from patients in surgical intensive care,” he says. “The crisis is different. The family dynamics are different. The culture of the nurses and doctors is different.” For that reason, each student’s training includes work in three units. “In the hospital,” he says, “that could be palliative care, neonatal intensive care, maternity, rehab, detox—it could be anywhere.” Different units are assigned depending on the student’s needs. “If we realize that the student may benefit from slowing down, they don’t need to be in intensive care,” Ellison says. “We talk with students about what would be helpful to them.”

In chaplaincy training, the classes generally have six or seven students. The foundation program, on the other hand, has about thirty at a time, and Hirsch says every one of the participants is transformed. “They become a community of people who work together beautifully. They come in and they don’t know each other at all, but by the end of the thirty-eight-week process, it’s amazing the intimacies that develop and the heart opening that goes on.” The students share with each other many aspects of their lives and losses.

“All of our students,” Ellison adds, “have been touched by death intimately.” Some have had cancer or another illness; others have experienced the death of a loved one. Sometimes the death was long ago, but through meditation practice the person realized how much the loss had affected their life and decided to investigate more through the center’s training. Learning contemplative caregiving is a way of healing, Ellison says, helping people to channel their painful experiences into being of service to others.

To date, NYZCCC has trained 125 students, which has developed into a sangha that stays connected and practices together, holding weekly meetings and annual retreats. The center also leads retreats and workshops for doctors, nurses, and social workers. O’Hara says she hopes that someday the center will be able to bring the skills of contemplative caregiving into the mainstream so they can be used by people of any faith tradition.

“Contemplative caregiving is really about learning to trust that you are enough,” Ellison says. “You’re perfect and complete just as you are. You don’t need to go into a patient’s room and perform tricks, or juggle, or anything else. You just need to show up with your whole body and mind.”