Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche was inspired to teach Western students by his own teacher, the Sixteenth Karmapa. “He told me many times that you’ve got to teach whoever is interested in the dharma,” says Chokyi Nyima, “and Westerners are really hungry.”

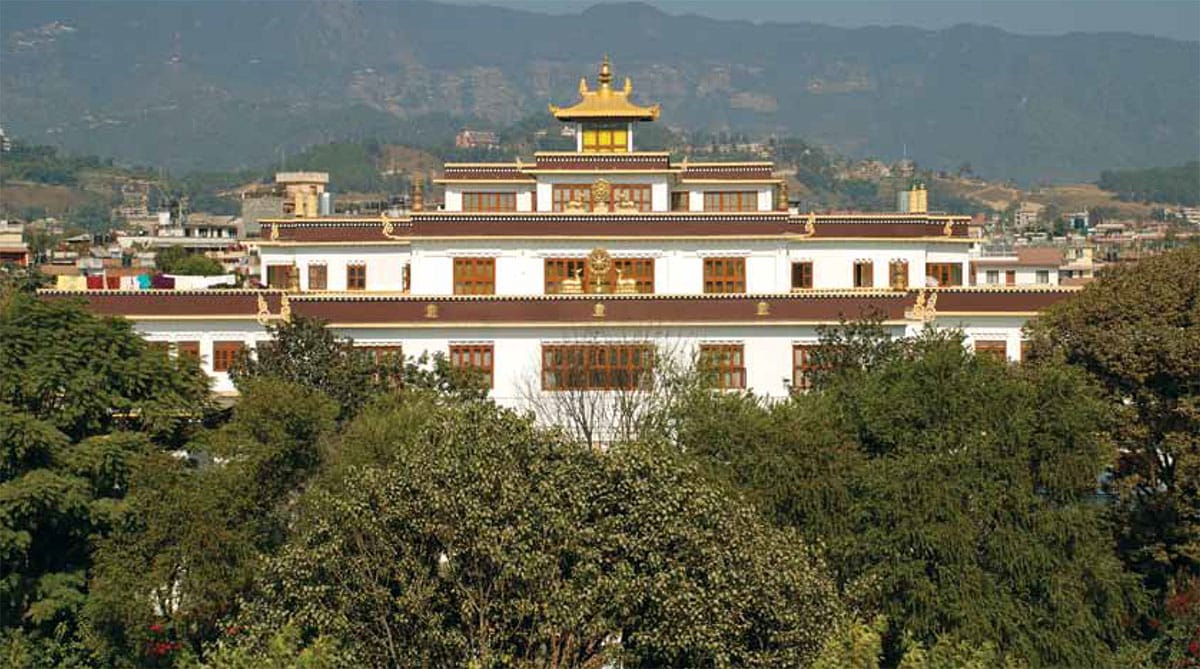

The firstborn son of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, Chokyi Nyima was twenty-five when he became the abbot of Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling Monastery in Boudhanath, Nepal, in 1976. He soon began to give weekend teachings to Western travelers, but thought it was important to offer nonmonastics (Western and otherwise) a more comprehensive Buddhist education. For this reason, in 1997, he established the Rangjung Yeshe Institute (RYI). On its own, however, the institute could not offer recognized degrees, so it joined forces with Kathmandu University in 2002 and formed the Center for Buddhist Studies. Today the center offers B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in Buddhist studies and Himalayan languages, as well as study abroad and intensive summer programs. Though now a branch of Kathmandu University, the institute is still located at the Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling Monastery and its classes are held at the monastery’s shedra, or monastic college.

A hallmark of RYI is that it combines the Tibetan monastic way of teaching Buddhist philosophy with modern academic methods. “Tibetans go much more in-depth on any particular thing that they study,” says program director Joanne Larson. At least at the B.A. level, “Westerners tend to be more about breadth.” When Larson taught Madhyamika, for example, she approached it in the Western way. Leading her students to look at several different Madhyamika texts, she taught them where the tradition came from in India, who the first Madhyamika was, what he had to say about it, and how the Tibetans interpreted the tradition. In contrast, the institute’s traditional Tibetan professors teaching Madhyamika would fully mine just one text. They’d talk about how people commented on that text but they wouldn’t delve into the broader history.

According to Larson, learning in both the Tibetan and Western styles is enriching for students, in that it encourages them to become more flexible in their thinking. It can also be an invigorating challenge for the faculty who hail from both traditions, especially for the khenpos, the Tibetan monastic professors.

“Our students are modern and most are Western,” Larson says. “They’re from a world where people are skeptical, where people question things. Tibetan monk students, for example, assume reincarnation is true because they’ve grown up with that idea, so they don’t say, ‘Wait a minute, why do you think reincarnation is right?’ but RYI students will ask that. Westerners think about things differently and we make different assumptions. This has been interesting for our khenpos and I’ve watched them change over the years. Some of them had never met a foreigner before they sat down to teach us. They’ve learned about us and how to answer our questions.”

Each year, the Rangjung Yeshe Institute has one or two visiting professors from the West, and Larson says they’ve all told her the same thing: they really like teaching at RYI because the students are so enthusiastic. “When the professors teach a Buddhism class in America, for example,” she says, “some of the students are taking it just to fulfill a requirement or because they think it’s going to be easy, but our students are in the classroom because they’re serious about studying Buddhist philosophy. The students ask good questions and have good discussions. They don’t sit there and send text messages to their friends.”

One reason that the discussions are so lively and rich is because of the diversity of the students; the men and women who attend the institute come from all over the world and are a range of ages. Additionally, since RYI began offering degrees, it has become more ecumenical. Before accreditation, the students were mostly committed dharma students of Chokyi Nyima, his father, or his brothers Tsikey Chokling Rinpoche, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, and Mingyur Rinpoche. Now, however, the institute is also attracting Buddhists from other traditions and even non-Buddhists. Larson gives the example of Boston College, a Jesuit institution, which has a study-abroad exchange program with RYI. Many of the students from Boston are Catholic. Generally speaking, they’ve taken an introductory course in Buddhism and would like to explore it further. They’re also keen to live abroad.

For students from North America, living in Nepal and attending RYI can be an eye-opening experience. “It changes you,” says John Harris, a student from North Carolina who is in the B.A. program. “You don’t have power or water all the time, and you have to live without a lot. Going back to the States for the summer, I realized how lucky we are to have all this great stuff, but also that we really don’t need that much to be happy—you can become a prisoner of great things. The whole Nepal experience kind of eases you up and gives you more patience for things. Since Nepal, there’s not as much restlessness in me.”

RYI students can choose to live on their own or with a Tibetan or Nepali homestay family. Homestays help students enormously with their language acquisition. “Some people really consider them family,” Harris says. “One friend who has been here about five years has always stayed with the same family and she loves it.” Homestays, however, are not for everyone, and Harris chooses to live on his own because he values privacy. Tibetan and Nepali culture is much more social than North American culture, and many Tibetans and Nepalis will think that they’re being bad hosts if they leave you alone.

“All that I have learned at RYI and in Nepal has been incredible,” Harris says. “But what has helped me the most are the teachings. I’ve studied texts that are from maybe the third or fourth century, and it’s awesome to see how relevant they still are today.”

“Buddhist philosophy is based on practice, not just theory,” says Chokyi Nyima. “At monasteries where monks study, they become good scholars, but the goal is not just good scholarship. Ideally, a good scholar should also become a good practitioner, and gain some realization. So I thought it was very important to have a proper place for whoever comes to Nepal to let them study academically and then apply the teachings.”