Do things really exist the way we see them? Do they exist as the separate, independent entities we usually take them to be? “I” and “mine” certainly seem to exist. This world with its mountains, rivers, oceans, and cities seems solid and reliable. Past, present, and future seem to be three different things. That’s how things seem to most everybody most of the time. But it turns out that if these things were ultimately real, we would be completely stuck, because liberation from the painful confines of this reality—the main promise of Buddhism—would be impossible.

If things existed the way we see them, all our fears would be well-founded and all our hopes would be worth struggling for. The inexorable cycle of birth, old age, sickness, and death would be the final truth. The Buddha would be wrong about ego because it would truly exist and egolessness would be impossible. Buddhism would be a delusion.

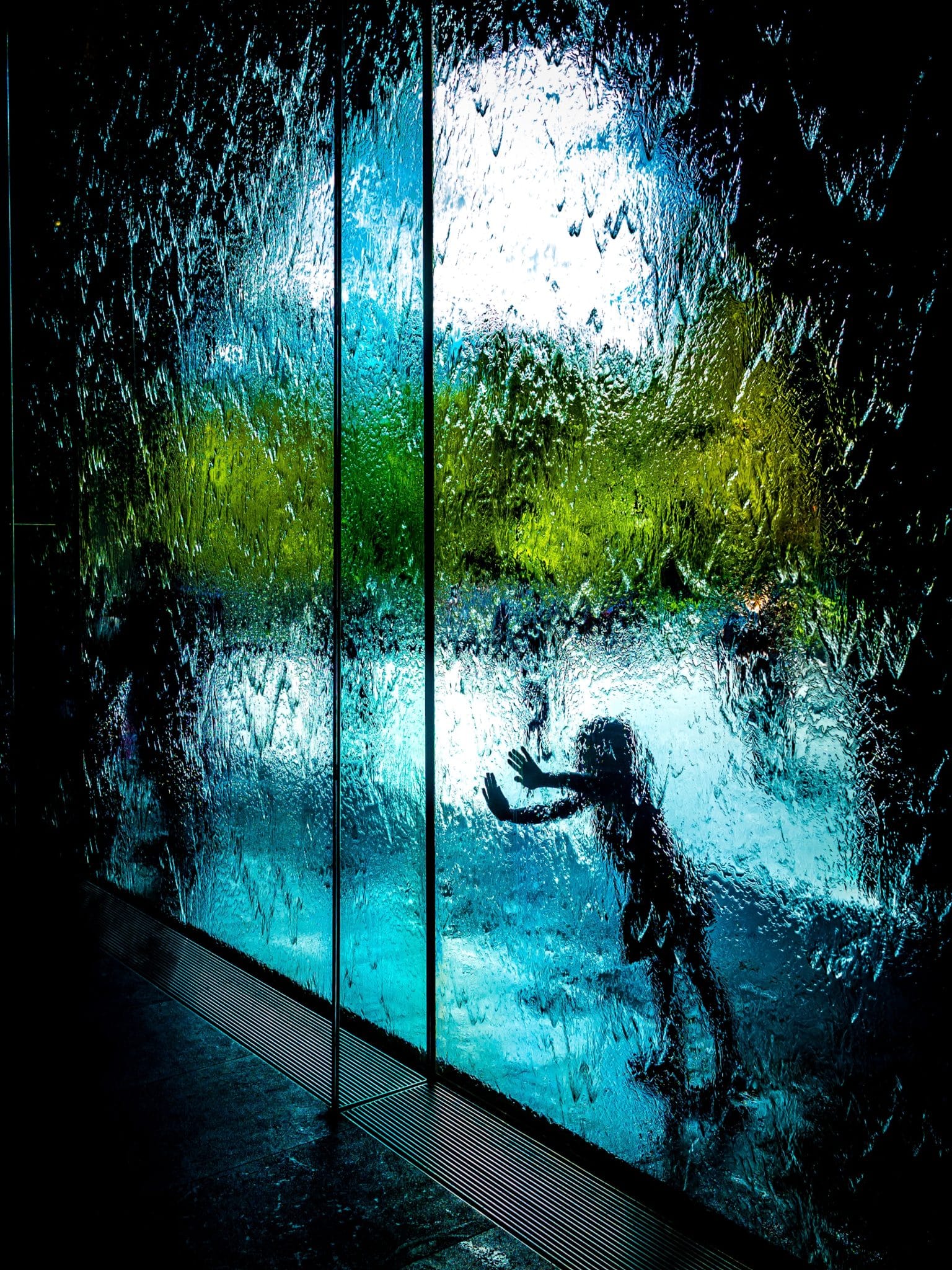

There seems to be a contradiction between the reality we expect and experience on a daily basis and the reality described by the Buddha. This is because the way things appear to us is not the way things truly are. There are two ways of seeing everything. Whereas we see a world that is limited, confining, and solid, buddhas experience the world as open, spacious, and relaxed. What we experience as suffering, buddhas experience as great bliss. How could that be?

Investigating the difference between the way the world appears to us and the reality proclaimed by the Buddha is a key practice in many Buddhist traditions. This practice of “contemplation” involves using our everyday thought process to help us discover how things are, and how they are not. This process gives direction to meditation practice and is also supported by it. Once you get the hang of it, contemplation not only leads to insight but also is enjoyable. It inspires us to go forward on the Buddhist path.

Contemplation invites us to question what we experience. The Buddhist tradition tells us that what we ordinary beings see are our own confused projections. Our seeing is obscured by basic ignorance and the delusion arising from that ignorance. This is what is called apparent reality. It is not the way things really are; it is only the way they appear to us. It is like the delusion that takes objects in dreams to be real when we don’t realize we are dreaming.

Buddhas and bodhisattvas who have overcome ignorance and delusion see ultimate reality. These realized beings see emptiness—the true nature of things. This is like recognizing a dream to be a dream. How can we transform seeing apparent reality into seeing the ultimate? The answer is found within us. It can be unlocked through careful contemplation. Contemplation can be done alone; it can also be done in a group and with the aid of a teacher. In any case, we need material to contemplate, and the Buddhist tradition provides ample choices. In this essay, we will take a step-by-step approach to contemplating emptiness. While contemplation takes effort and is sometimes frustrating, it is much more rewarding than just speculating about what emptiness is, which often just generates more concepts that obscure what the buddhas see.

Cultivating Insight

The contemplative process of transformation depends on cultivating insight. To do this, we need to look closely at our experience. Normally, when things appear to us, in the second moment we project concepts onto them and think the appearances are what we conceive them to be. For example, we see these black lines on the page and think they are letters and words. It is only because we are deeply habituated to reacting to these shapes in this way that sounds and meanings arise in our minds. We can’t see letters and words. We can only see shapes and colors. The process of projection happens so quickly that we don’t even notice it.

We constantly project our version of reality, this seemingly solid world. These projections are handy when we want to ask for some cinnamon on our cappuccino, but to realize ultimate reality we need to distinguish appearances from our own projections. Here are some simple contemplations that illustrate this. They are meant to be experiential rather than intellectual. Please try to approach them in as childlike a way as you can.

Think about this planet. No doubt it seems like you are on the top, but what about people 10,000 miles away from you? They feel equally that they are on the top of the world. If people in each location point “up” at the same time, they will be pointing in completely different directions. Up and down don’t truly exist either.

Next think about two people: one you like and one you find difficult. Think about a third person who doesn’t get on well with the person you like but gets on well with the one you find difficult. If you contemplate this state of affairs for a little while, you will understand that pleasant and unpleasant don’t truly exist either. If the first person was truly pleasant, everyone would see them that way, and if the second person was truly unpleasant, everyone would see them that way.

All qualities are like these: large and small, up and down, pleasant and disagreeable, beautiful and ugly, hot and cold, good and bad, light and dark, old and new, mine and yours. No one can deny appearances, but whatever appears is empty of whatever we conceive it to be. Ultimate reality, the true nature, is free from all conceptual fabrications. This is the meaning of emptiness, or shunyata, as it is called in Sanskrit.

Seeing Mirages

Basic ignorance is not recognizing the emptiness that is ultimate reality. It is the root cause of delusion and the bondage and suffering that come from it. It’s as easy as one-two-three. First, we don’t recognize the nature of what appears to our minds. Next, we generate desire, anger, or stupidity toward our projections, as if they were external objects. Finally, we make decisions, act, and react to what we have merely imagined.

To return to the dream example, when we don’t know we are dreaming, we might dream of being attacked by a snake, experience great fear, and try to escape from his fangs and writhing body—all without realizing that the snake was only made of dream stuff. If we can realize we are dreaming, fearsome images have no more power over us than a painting of a snake in a museum.

It is like the experiences and emotions we have while watching a movie. Even though we know we are sitting in a theater or watching TV, we still believe we see real people in real situations on the screen. We sit there thinking, “He’s going to fall in love with her.” “Don’t go in there!” “They’re all going to die.” It is nothing but colored light coming from a screen, but the illusion of a well-made movie is completely compelling.

Dreams and movies are good examples of what happens when we don’t recognize the true nature of appearances, and what happens when we do. In our daily life, when we think about someone we like, we don’t recognize the nature of what is appearing to our minds and think about that person with attachment, failing to see that we are thinking about our projection of a person rather than an actual human being. If someone we don’t like comes to mind, anger arises. It’s the same with jealousy, pride, and stupidity. All confused emotions arise in relation to our projections. In turn these emotions give rise to confused actions.

When a person happens to be right in front of us, we see or hear them, and in an instant project a concept on to what is merely a sight or a sound. Next, emotions arise toward the projection, and confused actions arise in response to that. This happens so quickly that we don’t even notice we are doing it. Our actions then give rise to new appearances, which give rise to new projections, emotions, and further actions. These chain reactions go on constantly. As the great Tibetan yogi Milarepa said, “Mind has even more projections than there are dust-motes in the sun.”

When we begin to recognize the nature of our projections, it is like waking up from a dream, or recollecting that we are merely watching a movie. Gradually, as we do this more and more, we start to experience freedom from our claustrophobic imagination and begin to experience the spaciousness and relaxation of emptiness.

What Emptiness Is

Sometimes when students of Buddhism first learn about emptiness, shunyata, they get frightened or angry, as though emptiness was something that would suck all the warmth from life, the way a black hole sucks in light. Emptiness sounds a lot like nothingness, which is clearly not what ultimate reality is. Shantideva, the great Indian practitioner and teacher who lived in the eighth century, made it clear in his classic The Way of the Bodhisattva that nothingness is not the meaning of emptiness nor the intention of teaching it:

It’s not indeed our object to disprove

Experiences of sight or sound or knowing.

Our aim is here to undermine the cause of sorrow:

The thought that such phenomena have true existence.

Sometimes people think that emptiness is a Buddhist philosophical concept, but the Buddha did not create emptiness; even if the Buddha had never appeared in this world, the nature of phenomena would still be emptiness. We teach emptiness to remove the suffering that comes from clinging to fabrications. It is not presented to destroy appearances. What the teachings on emptiness destroy is delusion, and the suffering that arises from it. Shantideva goes on to say:

Whatever is a source of pain and suffering,

Let that be the object of our fear.

But voidness will allay our every sorrow;

How could it be for us a thing of dread?

What we really need to be afraid of is ignorance and delusion. These are the causes of suffering. Recognizing emptiness is the antidote for suffering. It is what we need to embrace.

Emptiness is not easy to realize, because it is not an object for the conceptual mind. What does recognizes emptiness is prajna (Skt.), which translates literally as “highest knowing.” It is usually rendered as “wisdom,” “insight,” or “knowledge.” Prajna is basic to our makeup, but it is covered over by veils of concept and emotion. We need cultivation to bring it out. There are three ways to cultivate prajna: listening to the teachings, contemplating their meaning, and meditating. These three form a natural sequence.

Listening is straightforward. It includes both hearing teachings and studying them. We study such topics as suffering and its cause, the cessation of suffering, the nature of apparent reality, the nature of ultimate reality, and the general workings of samsara and nirvana. The prajna that arises from listening removes our coarsest misunderstandings about reality.

Contemplation takes the understanding that arises from listening and starts to mix it with our personal experience. There are many ways to contemplate. The simplest way is to reflect on what you have studied and ask yourself how it applies to you. Is all your experience tinged with suffering, for example, or not? What does emptiness mean? Is it something you vaguely understand, or is it clear to you that all phenomena are empty?

Another way to contemplate is to use questions that arise from your studies to investigate your experience, such as asking yourself, What is the nature of the enemy I’m thinking about? Is it really my friend arising in my mind, or is it a projection?

A third way to contemplate is to use logical analysis to clarify your understanding. You can ask yourself such questions as, Is this body one thing or many things? It must be one or the other, or else it does not truly exist. When you see the body is made of parts, you understand it is not one thing. And since the parts can also be broken down endlessly, at that point you can realize that its nature is emptiness.

Sometimes practitioners have doubts about the validity of contemplation. Since many teachings on meditation emphasize non-conceptuality, they feel it isn’t kosher to practice with concepts. This is an overly simplistic understanding about how to work with conceptual mind. Genuine freedom from fabrications comes from seeing through the delusion of concepts, not from suppressing them. If we don’t use concepts to develop prajna, we will have no way to develop it. Contemplation plays an essential role in transforming dharma from mere theory into personal experience. Through repeated contemplation, we develop confidence in the meaning of the profound teachings and confidence in our understanding. Gradually, we develop certainty about the meaning of prajna and shunyata.

Meditating transforms the intellectual understanding developed by contemplating into realization, or direct experience. Intellectual understanding only approximates ultimate reality. The genuine ultimate reality is beyond the intellect. It is inconceivable and inexpressible. We say that ultimate reality is emptiness, for example, but the genuine ultimate is even empty of anything called “emptiness.”

Nagarjuna, the great second-century master whose teachings refuted all extreme views of existence and nonexistence, described the characteristics of the ultimate (calling it the precise nature) in the Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way:

Unknowable by analogy; peace;

Not of the fabric of fabrications;

Nonconceptual; free of distinctions—

These are the characteristics of the precise nature.

Because it is beyond the reach of the intellect, ultimate reality can only be realized through meditation. There are two main aspects to meditation: resting and looking. These are sometimes called cultivating peace and cultivating insight. In the beginning, resting is emphasized, because first we need to pacify mind’s wildness. There is not much point trying to look around inside a whirlwind. As mind begins to settle, the emphasis shifts to investigating the nature of experience. At this point we alternate resting with investigating. This is the way to develop prajna through meditating.

It is worth mentioning that some people feel they need to practice resting meditation until their minds are completely still before they can move on to developing insight, and others feel that if they settle their minds enough, they will be freed from suffering and disturbances by that alone. Both of these approaches overestimate the role of resting meditation. It is insight that liberates, because it is insight that sees through ignorance and delusion.

Starting to Investigate

In apparent reality, such things as outer objects and inner mind; past, present, and future; me and mine; self and other; all seem to truly exist. In ultimate reality, there are no such distinctions. To understand, experience, and finally realize ultimate reality, we need to investigate apparent reality thoroughly so we can see that whatever we cling to is empty. Prajna doesn’t have just one thing to accomplish; it must accomplish many things.

There are countless ways to investigate. To give you a feeling for the process, here is a series of investigations that proceeds from what we discussed before, the emptiness of outer objects.

The outer environment seems solid and dependable because we always carry our projections with us the way a snail carries its shell. As the 1980s cult-film sage Buckaroo Banzai said, “Wherever you go—there you are.” While we are deeply habituated and cling tightly to our projections, they’re relatively easy to see through. We can begin by investigating what we think of as “home.”

Home appears to be as reliable as the earth, but when we look closely at our experience of home, all we find are glimpses of our front door, cooking smells, the sounds of people’s voices and flushing toilets, the feeling of snuggling into bed, the sight of the TV and perhaps pictures on the wall, and so on. We never find “home,” because home is merely a conception.

This is something we should contemplate. To do this, ask yourself, “Where precisely is this thing called ‘home’? Is it in the walls, floors, and ceilings?” If you think that is where it is, investigate each of them in turn to see whether they are anything other then collections of glimpses and tactile sensations held together by concepts. Investigate gradually. Look at all the experiences that seem to make up your home. By investigating in this way, you will find that home is in fact emptiness! The experiences conceived of as home do appear, but they are empty appearances. They have no base or support, no fixed, durable foundation.

Investigate “this planet” in the same way. You might feel that you know where various geographical reference points are located—Asia, Canada, Kansas, San Francisco. With your mind’s eye, see if you can find them. Are they in the east, west, north, or south? Did you take into consideration the curvature of the earth? How far away are they? Look at your experience of each reference point in turn. Is “Asia” anything more than the memory of a shape on a map? Can you ever find a whole city, or is San Francisco made up of lots of different glimpses the way home is? By contemplating in this way, you will understand that the planet and its geography are also projections. All outer objects can be investigated in this way, and you will find that all are emptiness. Outer objects still appear, but they have no essence.

Next, moving into more intimate territory, we should investigate the object of our self-clinging. The only thing we cling to more tenaciously than the external world is ego, the self. The self is our most precious possession, yet we really have no idea what it actually is. We think “I” and “mine” all the time, but what exactly are we referring to? If pressed, most people would say that it is their body and mind, although some would say it is something separate and more abstract, like a spirit or soul.

We need to deconstruct the actual experiences that seem to be “the self.” We see glimpses of hands and feet, clothing and reflections. We experience feelings, emotions, and other perceptions. We see reflections in mirrors, feel pleasant and painful sensations, get headaches and stub our toes. We think a lot, get sleepy, and sometimes feel uncomfortable. None of these is the self, and when we investigate we can’t find anything else that holds all of these experiences together.

You may protest, But all these things are part of “me”! If so, then ask yourself, What is it that experiences all these things? Is it something separate from the experiences, like a soul or spirit? Can you find such an entity?

Are thoughts the experiencer? If you think that thoughts experience things, then investigate what produces the thoughts. Can you find “a thinker” as well as a thought? Perhaps the experiences experience themselves. Is that how it is?

Look for the doer in the same way you looked for the experiencer. When you think, “I am going to walk the dog,” will the thought do the walking or the one who thinks? If it is the latter, then they must be two separate things and you should be able to identify both of them. For whatever action you experience, try to find the actor. Is the doer anything more than an assumption?

This is a difficult contemplation to do, so don’t rush or push too hard. We have a tremendous investment in the existence of ego, and there is incredible resistance to exposing this illusion. It is easy to dismiss such investigation simply as mind games or word play: it’s all semantics. But the Buddhist tradition of investigation is not based on playing games. The proof of the power of investigation has always been the result: loosening the grip of ego. Sensing this possibility, ego is amazingly resourceful at fending off investigation. All sorts of emotions, distractions, and confusion will come up to ward it off. Investigate repeatedly and you will gradually see that the self is also emptiness. It too has no base or root.

At some point you might conclude that there is no self, but there must be a consciousness that is the experiencer of all and the doer of all. If you arrive there, this is what you need to investigate next. The subjective aspect of experience is undeniable, but does this prove that a thing truly exists that is the experiencer? There are many types of consciousness—visual consciousness, auditory consciousness, smell consciousness, taste consciousness, tactile consciousness, mental consciousness, and self-awareness, to name the main ones. Is there a basis or unifying entity for all of these? Each of these consciousnesses is always conscious of something. Can you find mind or consciousness that is not connected with some specific experience? Can you find the root of mind?

Investigating the root of mind is an extremely subtle investigation. You might reflect on it from time to time to see if it illuminates itself. You could also refresh yourself by studying more, receiving teachings, and meditating. This gives contemplation more power to work on you.

Because there are two ways of seeing everything and we are deeply habituated to only seeing apparent reality, for realization of ultimate reality to develop, everything must be seen anew. Popular literature holds out the hope that this transformation can occur like a flash of lightning, but I am afraid this is wishful thinking.

Understanding, experience, and realization develop gradually through lots of listening, contemplating, and meditating. Meeting ultimate reality is more like exploring a new continent than a cosmic revelation, but the good news is that the journey of exploration itself is invigorating and endlessly rewarding.