In the summer of 1970, Jeffrey introduced me to the wonders of Tibetan Buddhism and to his own distilled grammar of the Tibetan language. My life would be completely different had I not met him at the University of Wisconsin as a first-year grad student in the Buddhist Studies program. He was a fourth-year grad student then, and one of the very few westerners already fluent in Tibetan and actively reading the philosophical texts that have fascinated me ever since he spoke of emptiness and dependent arising on the sun-drenched lawn of Tibet House outside Madison.

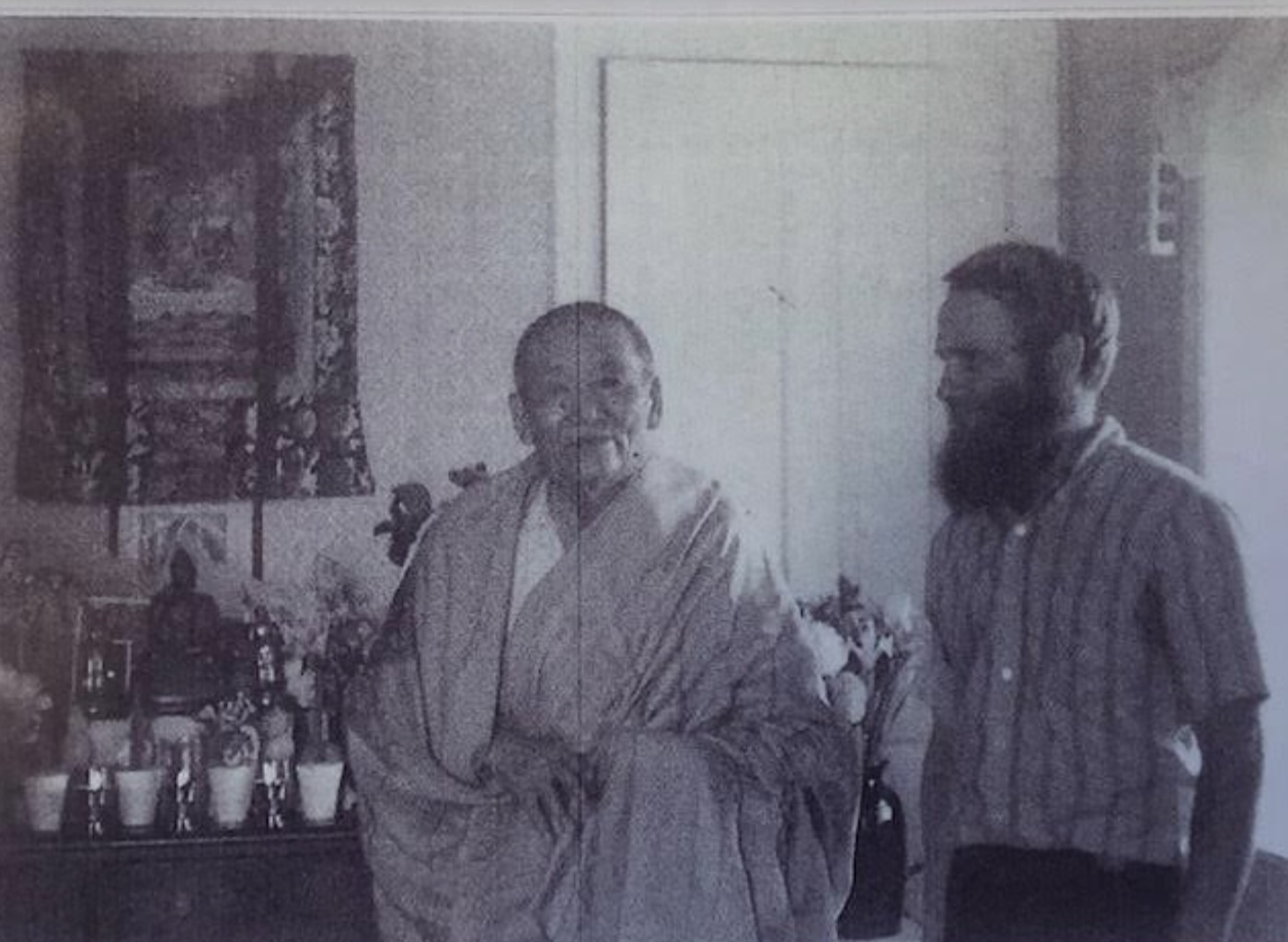

Jeffrey and Prof. Richard Robinson, head of the first Buddhist Studies program in the US, had founded Tibet House that summer, at least partly because the former abbot of the prestigious Tantric College of Lower Lhasa, Kensur Ngawang Lekden, had accepted their invitation to teach in the Buddhist Studies program the following year. He was 70 years old at the time, and his seat as abbot placed him at the very top of the traditional Geluk hierarchy in Tibet, just a few rungs below the Dalai Lama himself. He had spent the first 60 years of his life in traditional Tibet, escaping just before His Holiness. Kensur had been living in France until Geshe Wangyal, at whose Freewood Acres, New Jersey Monastery Jeffrey had lived and studied for about six years before coming to Wisconsin, invited him to this country. From there, he came to Madison. He would teach a seminar on Madhyamaka in the Fall of 1970, which Jeffrey would translate. I couldn’t wait.

To prepare us for this visit, Jeffrey taught a beginning course in Tibetan over the summer. We met on the lawn of Tibet House, where Rinpoche and several grad students, including me, would be living. We learned the alphabet, pronunciation, writing, and basic grammar. With the help of Jeffrey’s handwritten purple mimeographed sheets, we started to read the Prasangika chapter of Gonjo Jigme Wangpo’s Precious Treasury of Tenets. It was the best possible start for me. Jeffrey predicted that this famously condensed presentation would give us a map, a “place to put” whatever philosophical systems we studied down the road. For me, it was nothing short of thrilling. I had no idea such a thing existed in Tibet, in Buddhism, or anywhere.

Especially captivating was the rich vocabulary for different states of experience, these precise descriptions seemed to make visible another kind of world. Everything was described so rigorously, or sometimes poetically: the state of calm, the state of insight, the sequenced stages of meditative attention, the difference between direct experience, and getting at something by thinking about it. We were served a stunningly broad arc of knowing, from study, and reflection to variously nuanced states of contemplation. At the tail end of the 60’s, the most full-throated epistemological description I’d heard was, “Wow.” These articulations opened a new inner, yet not altogether internal, world of richness and rigor. There was so much to think about cognitively, to reckon with somatically, and to simply approach with wonder.

I shared my room at Tibet House with two parakeets. One day, inexplicably, one of the birds collapsed mid-flight in the center of the large room. Jeffrey heard me cry out in shock and came in to see why. He went over to the bird, still lying motionless on the carpet, and bent over, and the next thing I knew, that bird was flying as well as ever. What to make of that? Jeffrey left the room without saying anything. Several decades later, as I was recalling my amazement at that time, he allowed that he’d said a few mantras to my beloved bird.

That year Jeffrey offered me what later became his trademark as a professor, sitting down and showing a student how to read Tibetan on a topic of interest to them. In Madison, he introduced me to core texts of Madhyamaka philosophy, and made it possible for me to write an MA thesis that would have been years beyond my ken otherwise. The following year, our different paths overlapped for a while in Dharamsala, India, and I would often stop by and listen as hee would richly expand on whatever I was learning that day with my learned Tibetan teachers. This was while he himself was delighting in the opportunity to meet and then be invited to study directly with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, which led, in part, to his translating Tsongkhapa’s Great Exposition of Mantra and to a deep friendship — such that he was asked to translate for the Dalai Lama’s first decade of visits to the English-speaking West.

I got to read his early books as he worked on them and before computers were a thing, I typed out the manuscript of his epoch-making first book, Meditation on Emptiness. No Westerner, until that moment, had taken such a sustained deep dive into previously unknown treasures of Tibetan literature.

Soon after, Jeffrey got a job at the University of Virginia, where he established what is now pre-eminent among Tibetan Studies programs in North America. During his years there, he invited many of the most highly regarded Tibetan master-scholars of their generation, several becoming my close personal teachers, especially the Nyingma scholar and Dzogchen master Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche and Loling Kensur Yeshe Thupten. There was also a deep connection with Lati Rinpoche and Denma Locho Rinpoche. Jeffrey’s many compelling stories about Geshe Wangyal (1901-1983) inspired me to connect with him in 1971 and then visit him whenever possible for the rest of his life.

Jeffrey became my Ph.D. mentor, reading with me not only the texts I translated for my dissertation, but also other works related to it. In those early days, without Buddhist Digital Resource Center or any digital help at all, I could never have located or even known to search for such works. During his amazingly productive tenure at U.Va. from 1974-2005, in addition to teaching his famously information-rich classes, he read individually and weekly with each of his eighteen completed grad students for a year or two each, a scholarly generosity I have never seen matched in all my years in academia.

His presence at UVA. did not only impact the graduate students. Joanne Schneider, an undergraduate in those days, recalls:

“There was much excitement among the small group of Virginia students who had been meeting regularly for Zen meditation sessions led by a graduate Religious Studies student in the days leading up to the start of that fall semester.”

As word spread about Jeffrey’s prowess as a teacher and the compelling content he and Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche presented, his courses had the highest enrollment at the university. I am incredibly grateful to Jeffrey for the teachings he gave me, as well as the connections he facilitated.

Another undergraduate in those days was Don Lopez, who, along with Elizabeth Napper and myself, were part of the first Tibetan Studies graduate cohort when the program officially commenced in 1976.

Jeffrey published forty-eight books, translated into a total of twenty-two languages. He leaves us an extensive digital archive of translated texts and oral discourse from some of the leading Tibetan masters of recent generations, as well as many of his own iconic lectures. See https://uma-tibet.org/author-hopkins.html.

Throughout his long retirement, he continued translating new material or revising older work, now available on the UMA website mentioned above. Until recently, he actively tutored an international group of yet another generation of young scholars.

Jeffrey is survived by his current spouse, Hong-Ming Chen, and by Dr. Elizabeth Napper, his former spouse and lifelong heart companion, as well as editor-at-large of many of his writings. Hong-Min and Betsy tirelessly oversaw Jeffrey’s care as his cancer progressed over the last year and will be bringing his ashes to rest at his beloved residence in Virginia, which he called UMA, the Tibetan word for “middle way” and also, in this context, an acronym for Union of the Modern and Ancient, in both a broad and distinctively Tibetological sense.

Like so many of his students, especially the early ones, I have no idea what my life would have been like without Jeffrey. He made it possible. No one of my generation or background had childhood dreams of growing up to read and study Tibetan. His pioneering vision, no doubt sown with seeds from past lives, made so much possible for so many. Thank you, Jeffrey, and be well wherever you are.