Whether they’re looking at looted Greek antiquities, stolen indigenous artifacts—even remains—or Jewish-owned art pillaged during World War II, museumgoers often overlook just how exactly these pieces came to be in a museum’s possession. This question of provenance arose for artist Phung Huynh when reflecting on thousands of decapitated Buddha heads from Asian countries in museum collections around the world.

Indeed, Buddha heads have become common decorations in gardens and restaurants to evoke peace, mindfulness, and wisdom. For Huynh, however, those Buddha heads are symbols of religious violence and colonial theft. “There are thousands of Buddha heads and fragments in museums in America, Europe, and Australia that need to be returned to Cambodia,” she says. “When my boys and I were visiting these ancient temples and cemeteries, we saw a lot of headless Buddhas. That was very heartbreaking. For us, these statues are not objects—they’re manifestations of Buddhism, they’re divine, they’re vessels for the divine and for our ancestors.”

“Buddha statues, sculptures, and paintings have always been in my life. I didn’t call it art or consider it part of my art until recently.”

Phung Huynh is an award-winning artist and educator whose work explores how cultural identity is, as she puts it, “a continual shift of idiosyncratic translations,” especially how “cultural ideas are imported, disassembled, and then reconstructed,” and in doing so, highlights “(mis)interpretations and (re)appropriations.”

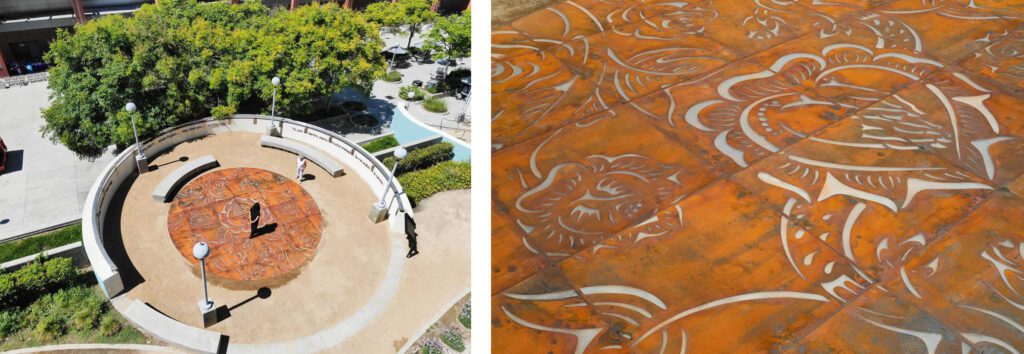

Huynh’s public art projects can be seen throughout Los Angeles County, including in the Los Angeles Metro and the Los Angeles Zoo. Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center features her work Sobrevivir, a large-scale sculpture honoring the women impacted by coerced sterilization practices at LAC + USC Medical Center in the 1960s and 1970s. Huynh’s Cambodian family’s history and Buddhist heritage influences her upcoming show, Return Home, in Los Angeles.

During the Khmer Rouge, Huynh’s father fled Cambodia to escape Pol Pot’s genocidal dictatorship, and in Vietnam he met and married her Chinese mother. Huynh was born in Vietnam, but soon she and her family left as refugees sponsored by a church, ending up in Mount Pleasant, Michigan. However, with their sponsorship came pressure to get baptized.

“My parents couldn’t say no,” Huynh says. “I was baptized. Our whole family had to go to church every Sunday. But we still practiced Buddhism at home. We practiced and honored our holy days.”

They eventually settled in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. She drew as a child and wanted to make art her vocation. “My parents never wanted me to be an artist,” she says. Mom said, “We didn’t survive war and genocide for you to starve and be an artist!”

While at the University of Southern California, Huynh told her parents she was studying medicine, but she took art classes instead. She eventually transferred to Art Center College of Design to study illustration, later earning her MFA in studio art at New York University.

“The resilience and tenacity that my parents have as refugees, ironically, is the same spirit that makes me believe I can be an artist,” says Huynh.

Now, her work is included in collections at the Dallas Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the USC Pacific Asia Museum, and the Vincent Price Art Museum among others.

Though she’s been exhibiting for over twenty years, integrating Buddhism into her work is a recent phenomenon.

“In the last six years, I have been actively seeking my own personal practice in Buddhism,” she says. Prior to that, Buddhism was something she did only on holidays, such as while observing Lunar New Year. However, going to temple left an indelible impression on her. “Buddha statues, sculptures, and paintings have always been in my life. I didn’t call it art or consider it part of my art until recently.”

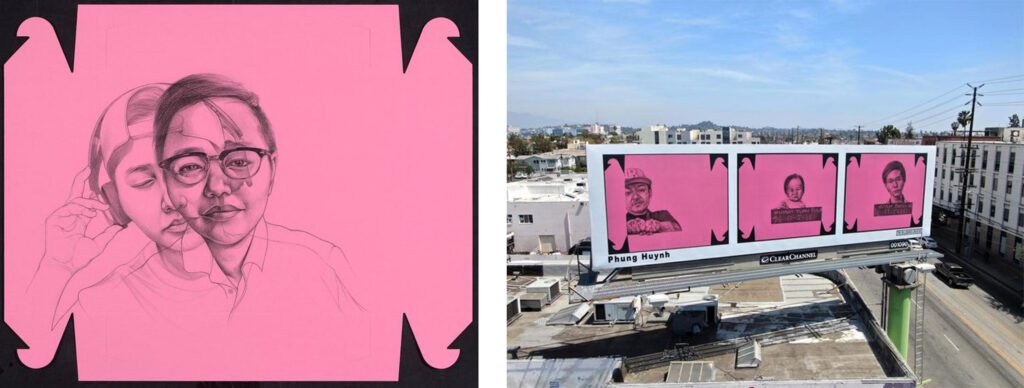

Huynh’s work grows out of her Southeast Asian background. Her most recent project was The Pink Donut Box: Tracing Stories of Cambodian and Vietnamese Refugees. In her words, the project explores how “close to 90 percent of California’s donut shops are mom-and-pop businesses run by Cambodian immigrants or Cambodian Americans (Khmericans). The trend that links pink boxes with donuts can be traced back to the Khmerican donut ecosystem.”

Portraits of refugees are drawn onto the pink boxes, unpacking “the complexities of immigration, displacement, and cultural assimilation with Southeast Asian communities.”

On a recent family trip to Cambodia, which is over ninety-five percent Buddhist, Huynh realized, “You can’t remove Buddhist identity from Cambodian identity—they’re inextricably linked. You can feel it. It’s kindness. It’s compassion.”

Cambodia has a rich and storied past. Famously known for the ancient city of Angkor Wat, home to thousands of temples, sprawling for miles. Angkor Wat has been described as the largest religious monument in the world. Today, as it has been for thousands of years, it’s a sacred place of worship.

So, Cambodia is known both for its spiritual life and for the brutality of the dictator Pol Pot. When the United States tried to destroy the Viet Cong hiding along the Vietnamese/Cambodian border, President Nixon made the decision to bomb the area. Over two million tons of bombs fell over 100,000 sites—not all of them along the border. This rampage led to the rise of Pol Pot’s administration, one that wanted to revert to an agrarian society. Anyone seen as educated was killed. Even wearing glasses—a sign that one could possibly read—was cause for execution. Pol Pot’s regime ran from 1975 to 1979. By the end of his reign, one in four Cambodians was dead. This genocide is part of the Cambodian psyche.

“Buddhism is about deepening our compassion through suffering and how to overcome suffering,” Huynh says. “I really do believe that being Buddhist is rooted in our ability to survive.”

Indeed, Cambodian Americans have long used Buddhist spiritual practices to deal with their post-traumatic stress. Perhaps repatriating Buddhist art back to Cambodia could be a part of that healing.

Huynh is currently delving into this deep and complex journey. “I always describe Cambodia like the heart that beats out to the arteries,” she says, “where all of us are kind of scattered all over the world as refugees. We always have to return to the heart. All these fragments and heads that are in Europe and America and Australia eventually have to go back somehow.”

Her next show will be at the Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. “I’m drawing these heads,” Huynh says, “but I’m also making artwork of the bodies with the missing heads and displaying them in the space.” She will incorporate classical Cambodian dancers “to activate the space, spiritually uniting the heads and the bodies.”

She admits that exploring this new exhibition was a painful process. The decapitated heads speak of the emotional pain of a country. However, she doesn’t want that pain to define her or her community.

“We don’t want to be defined by our oppression and suffering. We deserve to be happy, deserve to celebrate. I want to pass on joy, not trauma, to my sons. I want them to remember where they came from and how resilient their ancestors are, using Buddhist practice to transform suffering into joy.”

The show will lament and mourn the decapitated heads, but Huynh wants to focus on the return to wholeness of reuniting the head and body. In the same way, Cambodians were separated from Cambodia, one can always return and feel a sense of connection. As she says, “You can always return to the heart that beats for all of us around the world.”

Return Home will run at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles from June 22 through August 3, 2024.

This article was published in the June 2024 issue of Bodhi Leaves: The Asian American Buddhist Monthly.