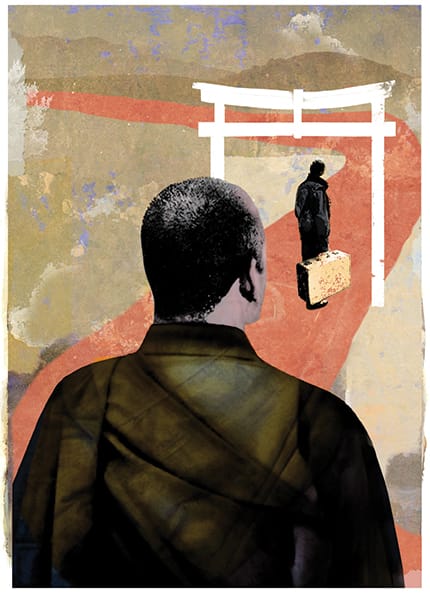

Doing the right thing doesn’t always mean following the rules, says Edward Brown. He only wishes he had known that years ago when he was deciding the fate of a young Zen student at Tassajara.

Once Katagiri Roshi told us, “Practicing Zen is not like training your dog: Sit. Heel. Fetch. We are not training ourselves to be obedient and to just follow the rules. We are training ourselves to wake up.” When a teacher says this, you know he’s seen a lot of people trying to get it right. And failing. And being miserable.

Katagiri Roshi would also say, “The meaning of life is to live” and “Let the flower of your life force bloom.” Not an easy task when so much by-the-book structure appears to demand compliance. Still the wisteria grows freely using the trellis for support.

To be in the grip of rules is a fearsome place to abide. You know what you’ve done, so you are always on the run from the Zen police, trying to hide and cover up the lapses, seeing if you can face down the authorities. How discouraging it is to find out that you are playing every role yourself—and there is no one else to blame. You cannot escape the whole charade. You know what you’ve done, so you know

the authorities know what you’ve done, and you know the judge will judge you accordingly. And you, along with the others, will conclude, Darn, I’m no good at following the rules, even though I’m great at catching myself and passing severe judgments. I’ll never be able to get it right.

Then you hear Katagiri Roshi saying, “It’s the flower of your life force blooming, don’t you think?” And you don’t know what to think.

Our most common strategy is to try to measure up, to attain perfection and not have any lapses—zero tolerance, buddy. And you, being the intrepid, alert policeman, catch the smallest infractions: You did not stop at the stop sign. I don’t care if you’ve never been caught before in fifty years of driving. That wasn’t a stop. Bad dog!

Once you are aware of the whole process—an activity followed by an assessment; assessment followed by judgment; judgment followed by discouragement (and perhaps shame); discouragement followed by unconscious behavior—you begin to sense that you are involved in dog training. While you’re aiming to correct bad behavior, you’re unwittingly contributing to it—your bad dog does everything it can to avoid being anywhere near your heavy judgments about yet another (fun, painful, silly) activity temporarily out of sight of the authorities. As the judgment becomes more intense, the avoidance behavior increases. You begin to suspect that it’s time to make changes in your dog-training protocol, and bit by bit, you notice that changing any part of it changes all of it. As Shunryu Suzuki Roshi says in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, “If you want to control your sheep or cow, give it a large pasture.” When you the judge lighten up, your goodhearted awareness stops trying to run away and begins making itself at home.

Speaking of Suzuki Roshi, there’s a story that David Chadwick tells in Crooked Cucumber that goes straight to my heart. I first met David in the spring of 1967, when I was head of the kitchen and David was head of the guest dining room at Tassajara, and though David and I rarely see each other now, he abides tenderly in the sweetness of my heart. It’s one of the understated, remarkable aspects of Zen practice that we develop dharma friends that last a lifetime (or perhaps innumerable lifetimes).

I was extremely introverted, and still tend to keep to myself, while David was extroverted— possibly the most outgoing person ever to practice at Zen Center. Zen students spend so much time sitting silently facing the wall that they rarely have opportunities to be social. Extroverts need not apply—and usually don’t.

I recall one day at Tassajara, as I sat with David in the sycamore grove beside the office, everyone who came by stopped to talk with him (they weren’t pausing to speak with me). Each of them seemed to be continuing an ongoing conversation with David. Friendly, responsive updates were given and received as the sunshine sparkled in the blossoming maple trees and the budding sycamores. I sat in the warm light and soaked it all up in silent amazement. We are such different people, I thought.

While the winters at Tassajara are devoted to two ninety-day practice periods for Zen retreatants only, summers are open to visitors as well. Zen students at Tassajara are directed not to drink alcohol. What can be challenging for some is that summer guests were and still are allowed to bring alcohol. In the summer, students follow a schedule of meditation and work (on scholarship), while guests pay to enjoy the hot baths, the quiet contemplative atmosphere, and three daily vegetarian meals. Income from the guest season helps support students year-round.

At times, students see the guest season as an opportunity to develop skills and virtues that are not normally cultivated in the winter, such as being of service, practicing graciousness and generosity, learning to perform when called upon—as in work where there are consequences—and potentially acquire people skills.

Others find the summer to be a distasteful disturbance to the inner and outer peace and quiet of the winter months. If peace and quiet is the point (sit, heel, fetch!), then staying at Tassajara over the summer certainly becomes a travail. As my friend Daigan says with magnificent dry humor about a distant summer: “The heat, the flies, the madness, and the lies.” Which life will you train for? Classically, Zen students are said to have mouths like a furnace (you take it all in and burn it up, fuel for growth) and minds like a fan in winter (useless!).

During the summer, David was apt to sit down with the dining room guests toward the end of the meal, share some of their wine, and visit. After cleaning up, he would head off to a guest’s cabin and continue visiting, often shifting to brandy or scotch, and then the following morning he would miss the student schedule of zazen, service, and breakfast. The guest season was an opportunity for David to be David.

Behavior such as this does not go unnoticed in a Zen center. One day during chosan, the morning meeting of temple officers with Suzuki Roshi, the director brought it up. Each chosan began with silence while Roshi’s attendant prepared tea. After the tea was passed around, everyone would bow together, following Roshi’s lead. The tea was sipped in silence until Roshi spoke. His announcements or concerns would lead to his invitation for others to speak: “Is there something you would like to bring up?”

With David sitting nearby (after missing the entire earlier schedule), the director asked, “Roshi, what do we do with someone who is always breaking the rules, drinking alcohol with the guests, and missing morning meditation?”

Suzuki Roshi paused, cleared his throat, paused again, and said, “Everyone is making their best effort.”

Persisting with his inquiry, the director said, “But we’ve got to do something. He’s breaking the rules flagrantly and persistently.” Roshi responded, “It’s better that he does it in the open, rather than hiding it from us.”

Again the director pressed his case: “We can’t let this behavior go unpunished. It’s a bad example for others.”

Roshi replied, “Sometimes someone is following the spirit of the rules, even if he is not following the letter of the rules.” That exemplified Roshi’s exquisitely gentle firmness, his utter conviction.

“Wouldn’t it be better if he followed the letter of the rules and not just the spirit?” came the director’s further challenge. “Yes, that would be best,” concluded Roshi.

Right, wrong, good, bad—often I don’t know what to say. David got to stay, and he continued being David. I rarely went to the morning meetings with Roshi, as I kept working in the kitchen, and my lessons came from cutting a hundred thousand vegetables. I like to think that Suzuki Roshi knew David’s heart, and knew it was in the right place. How shall we understand this human life, intrepidly wayward, intrepidly seeking the way?

I think it’s well worth noting that for many years after Suzuki Roshi’s death in 1971, David was the one who championed him, telling everyone that we needed to preserve Roshi’s lectures and establish an archive. Disciples much better at following the rules did not have this inspiration and did not readily agree to support David’s efforts. Little by little David carried the day, running up large debts in the process. (I think that he should receive a grant to be David, as he is so phenomenally good at it.) It took a while, but David eventually got sober, and there is a new quietness, focused and alert, receptive and curious, that has deepened his easy engagement with others.

David’s story touches me. What is it, finally, that helps people, awakening their good hearts? I know that Suzuki Roshi also wanted others doubtful of their worthiness to stay at Tassajara and continue practicing Zen. I wish I had known this story when I was head resident teacher at Tassajara in the spring of 1984. Although that chosan had taken place in the sixties, I did not know about it until David’s biography of Suzuki Roshi, Crooked Cucumber, came out in 1999, so I did not have Roshi’s example in front of me.

One day during the spring of 1984, the officers of the temple, serious and stern, came to inform me that one of the students, James, had been doing drugs and sharing them with others. Unfortunate news, I thought, as I sat in the crisp spring air with sunlight flooding in the windows of my cabin. “What shall we do?” they asked. I said, “Please, let me speak with James before we decide anything.”

James was an energetic, occasionally moody young man with a disarming smile. He was by far the youngest student at Tassajara, perhaps eighteen (or was it twenty-two?), and he’d come to Zen practice off the streets of San Francisco after being discovered by Issan Dorsey, one of Zen Center’s priests. Rumor was they had been lovers. Now James was following the schedule at Tassajara—Issan was not there—where he slipped easily into the role of mascot rather than hero, scapegoat, or lost child.

Sitting down together in my cabin by the upper garden, I found James to be entirely forthcoming. It had been his birthday recently, and his mother had sent him a care package, only instead of the usual chocolate chip cookies, there were brownies laced with hashish, marijuana for smoking, and some LSD. What a mom! But what was she thinking, sending drugs to a Zen center? Why wasn’t she thinking?

James said that the package had entirely way too many drugs for him to consume on his own, so naturally he had shared them with others—on their day off, of course.

James also expressed his remorse and his deep wish to continue practicing at Tassajara. He loved being there, and he especially loved Suzuki Roshi. I told James that I would do my best, but I wish I’d known how to make his wish come true, known the story about David and Suzuki Roshi, known to consult with others outside of Tassajara. When I met with the officers, I told them I wanted James to stay, but they were insistent that he had broken the rules and had to leave. I argued that he would soon be back on the streets of San Francisco, and that he probably wouldn’t survive for long. The officers said that was up to him; that he had to leave. I finally agreed to go along with them. Heaven help me.

James may have lived for a while at our City Center, but soon he was back on the streets, and after a year or so we heard he was dead. How painfully sad. Of course we don’t know what would have happened had he stayed at Tassajara, but an isolated canyon in the mountains does not have the temptations of the streets of San Francisco, and today I remain heartbroken not to have kept him in that structured isolation, where we could have provided him with a big brother or mentor, where the spirit of Suzuki Roshi would have welcomed him: James, please stay, do your best, let this practice take care of you. Though you break the rules, come back to the Way.

Zen practice is not like training your dog: Sit. Heel. Fetch. Some of us dogs have taken years to mature. What finally helps is hidden in the heart, waiting to be uncovered. Sometimes by a teacher. Sometimes through sorrow.

My brother Dwite attended the first practice period at Tassajara that began in July of 1967, and when he left after a month, I didn’t know why. He went on to become first an Episcopal priest and then a Catholic layperson. Finally a few years back, we talked about it. He said that one of the students had been bugging him about his imperfect attendance in the zendo—he was remembering that it had been David Chadwick, of all people! He said he loved to sit and watch the creek, but he was being pestered relentlessly (so it seemed) to follow the schedule. David does not remember doing this, and my brother agrees it may well have been another student.

Finally, Dwite went to tell Suzuki Roshi that he was leaving. Roshi effusively encouraged him to stay, saying, “Please don’t worry about it. Don’t worry about what the other students say. I need you to stay.” And then my brother said, “Roshi got up and hugged me.” He didn’t know what to make of it. “What did he mean, that he needed me to stay?”

Roshi’s efforts could not dissuade my brother from leaving, as he was set on not having to weather the harassment any longer. “I just didn’t like it,” he said.

“The Great Way,” Dogen says, “circulates freely everywhere. How could it depend on practice and realization?” On going or staying? On how well behaved you are? The meaning of life is to live. Suzuki Roshi said that the best instruction is person to person. When there are too many people for this, we have rules.

What, finally, are the rules to live by? Woof! May the flower of your life force bloom. Freely and fully.