A friend said that meeting Shodo Harada Roshi for the first time in sanzen, a private interview between student and Zen teacher, was like “sitting in front of a nuclear reactor.” That was my experience too, and it is not much different the next time either…or the time after that.

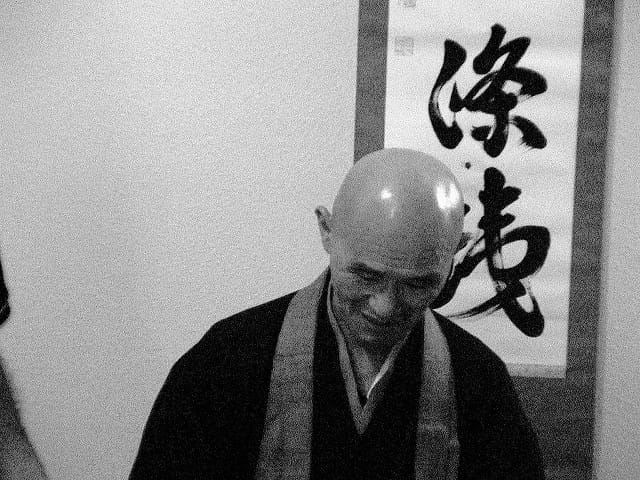

Shodo Harada is a teacher of extraordinary energy and depth. He is a Rinzai Zen priest with the unusual calling of teaching Westerners. He is abbot of Sogenji in Okayama, Japan, and Tahoma Monastery, on Whidbey Island in Washington. He also supports zendos and sitting groups elsewhere in the United States and in Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Switzerland, and India.

At Sogenji, Tahoma, and in his various travels, Harada Roshi works closely with Priscilla Daichi Storandt. Chi-san, as she is familiarly known, is his dharma sister and a fellow student of Yamada Mumon Roshi. She followed Harada Roshi to Sogenji and serves as his translator for talks and in the intimate environment of sanzen. Her warm, joyful, no-nonsense presence perfectly complements Harada Roshi’s drive. They are quite a team.

Sogenji was built in the seventeenth century as a retreat for the Ikeda clan, who were warlords, or daimyo, in the Bizen region. Harada Roshi, Chi-san, and I met over two days in what had been the daimyo’s scriptorium, overlooking Sogenji’s garden and pond. We had a second interview at Tahoma, during sesshin. Roshi responded to each question in Japanese, with his deep and raspy voice, turning inward at times to search for words, which then emerged in bursts of urgent expression.

I am deeply grateful to Chi-san for her on-the-spot translations, and to Tom Yuho Kirchner, who later meticulously transcribed and translated the interviews, checking with Chi-san to get the flavor of the moment.

–Hozan Alan Senauke

Alan Senauke: Roshi, how did you come to Zen training?

Harada Roshi: I was born in a Zen temple in Nara. But truly I began to practice because of a chance encounter with my teacher, Yamada Mumon Roshi. One day in high school, I was on an errand to Myoshinji for my father. I boarded a bus at rush hour and toward the back I noticed an old priest in robes, reading a book. As I stood in the aisle — a youth who lived in a temple because of the circumstances of birth — I was deeply moved by this man who seemed so deep and so still, and radiated such brightness of spirit. In comparison, the people around him seemed melancholy, weighed down by their thoughts and cares.

I decided to see where he would get off. He left the bus at Myoshinji, exactly as I did. I followed him to Reiun-in, a subtemple of Myoshinji. Later I learned that this was Mumon Roshi, Reiun-in’s priest, abbot of Shofukuji monastery in Kobe and president of Hanazono College, the Rinzai Zen college in Kyoto.

This encounter made me realize how limited my understanding of Buddhism was. I doubt I would have become a monk if I had not met Yamada Mumon Roshi. Because of him, I realized how a person’s inner qualities can shine clearly from their entire being. So after graduating from college, I entered Shofukuji to train under Mumon Roshi. My life today is entirely the result of my encounter with him.

When did you come here to Sogenji?

One day Mumon Roshi said, “There is a temple in Okayama called Sogenji, and the old priest is having a hard time keeping it up by himself. Would you help him out?” The old priest was the late Kansei-san, the retired abbot of Sogenji. That was more than twenty years ago.

The training dojo at Sogenji had closed seventy years earlier. We started doing things as we had at Shofukuji — getting up early, spending our days doing zazen, cleaning, and so on. At the beginning there wasn’t much of a plan. There were only two or three of us here.

Sogenji and Tahoma have developed uniquely as training centers for Westerners. How did that unfold?

Mumon Roshi emphasized that in spiritual practice there is no East or West; what is important is the bodhisattva’s presence. It doesn’t matter whether one is lay or ordained; the desire to seek the Way is the sole criterion for training. In Japan, Zen priesthood has become a kind of occupation. For those who cross the ocean to practice, Zen is more than a mere job. People put their futures on the line for the sake of practice.

In the last forty years, many great Japanese teachers have come here because they found in themselves an affinity for the West. Why?

It’s a natural flow. Humans lean in the direction of what they are seeking. It is natural to want to teach those who have a desire to learn. Even if you are in the land where you were born and brought up, if nobody around you is interested in what you have to teach, you are not going to be interested in teaching them. Same goes for Ichiro Suzuki, the baseball player. It makes sense for him to want to be in a country where they really get his sense of playing.

What do you think we Westerners need in order to develop our understanding?

The most important thing to develop is love for people and love for one’s country. Without that, we fall into conceptualization.

What do you mean by “love for one’s country”? How do we express that in our practice?

What we receive from our country — our safety, our livelihood, our upbringing, our cultivation as a human being — does not refer to a political system, or to a present government, but to this place where we live. I don’t mean profit making or benefiting the country’s political situation, but appreciating our home, this place.

How does one love one’s country without succumbing to nationalism?

As the sutras say, we must let go of all notions of a self, a being, a life, or a soul. Unless we overcome these, we go astray in our attempts to love other people and love our country.

This is a difficult question right now in America. The deep love we have for our country is often confused with the political system that supposedly maintains that nation. Our leaders play on our patriotism when they undertake political and military adventures. One might call it nationalism. This is a dangerous tendency, I think. How can we cut through such delusions?

People should not support a system in which humans kill other people. We can’t support that as Buddhists.

You can’t answer this question in the abstract, though. We have to go case by case. But to draw a clear line, it is the teaching of the Buddha that we must not create conflict and we must not kill. If at some point one had to choose between what the country is doing and one’s beliefs as a Buddhist, one should certainly choose the point of view of the Buddha.

Zen at War

Roshi, I know you have been concerned about the role that Japanese Buddhism, and particularly the Zen schools, played in World War II. Why did the Zen organizations fall into error?

Overcoming the concepts of self, being, life, and soul must be accompanied by a strong social sense, a consciousness of the true social situation in the world. Without this, one can inadvertently be swept along by circumstances.

What is the true social situation in the world?

There are different views of the world. For example, there is the scientific view, which lacks the spiritual point of view. And what people are getting from various media is often filtered through the wish to make profit, the wish for people to see things a certain way — it’s totally undependable. So we can never know what is really happening in the world. This has always been the case, but it is especially true right now. In the past, people were handicapped by not having dependable information. But today, the distortion of information is a great problem.

Apart from the media, what do you see as the true situation in the world?

Countries and their leaders don’t see existence as made up of individuals. They mainly see what is going to bring material profit. People in a country are like parts of a machine, to be used for that end.

In the case of Japan during World War II, would you say that the Buddhist priests and leaders who supported the war were realized people?

These Buddhist leaders may have been less than completely liberated from the concept of ego. One can be internally liberated and still have much work left to realize liberation in the context of society.

But often it is extremely difficult to express a position that goes against public opinion and the government’s interests. This applies also to the situation in America after the terrorist attacks. We mustn’t fear this challenge, however.

Although Buddhist leaders during World War II may have had great individual insight, they had a very limited understanding of the world outside Japan. This, I believe, was one of the main reasons for their serious errors in judgment.

But what was their understanding of Buddhism?

Of course they understood and admired the Buddha, or they would not have been teachers.

What allowed them to support a violent kind of nationalism, on the one hand, and support Buddhism on the other? It seems there is a kind of split.

There is a teaching of the Buddha about unifying the whole world in the dharma. That is probably how the Zen teachers would have supported the Japanese military. But the question is why would they agree, misinformed as they may have been, to the use of force to accomplish this? In the scriptures, the Buddha intervened three times when his country was threatened, but to the end, he refused to sanction the use of force to protect his country.

Kensho and the Precepts

This raises the question of what is kensho, or what is the nature of liberation. What is the importance of kensho? Do you encourage your students in this direction?

Of course. If I didn’t, it wouldn’t be the teaching of Shakyamuni. People tend to conceptualize kensho, though, imagining it to be a kind of supernatural phenomenon, like a divine light or a vision of the Buddha. Kensho is not a concept or abstraction external to us. The essence or ground of mind cannot be sought outside. That essence, common to every human being, is a truth (shinjitsu) that anyone can awaken to and verify within his or her own mind; it’s something internal that appears when all accretions are gone.

Is there a distinction between kensho — in the sense of realization — and character development?

When speaking of kensho, it isn’t necessary to get involved with matters of character or personality. The central issue is, when seeing, how do we see? When hearing, how do we hear? When smelling, how do we smell? When tasting, how do we taste? When touching, how do we touch? When thinking, how do we think? These functions of our mind essence are common to all people.

What is the interplay between our conditioned nature and our true human nature?

That conditioned personality is buddhanature. But whether or not you can use that conditioned personality is the function of buddhanature.

We have to realize that buddhanature is not our own personal thing; it is connected to everything that is. Because we all think it belongs to us, we make mistakes in how we use it. Even though we think we understand, the problem is we make it private and try to turn it into our own personal thing.

In the teachings of Bodhidharma, one point of entry is through sila, or precepts. Does kensho necessarily encompass right action in accordance with the precepts?

We must keep in mind that the precepts are basically social. They are not necessary in any primal sense. An infant has no need of the precepts. One expression of the precepts is living a clear, orderly life on an individual level. The precepts become necessary when we start to deal with other people in society.

The Isshinkaimon, or “The Precepts of One-Mind,” attributed to Bodhidharma, discusses the precepts from the standpoint of jishou reimyou, “original mind, mysterious and beyond all human understanding.” This is our very essence, the mind of kensho. In this original spiritual essence, there is no urge to kill, to steal, to lie, or to injure, and thus no necessity for the precepts. Our behavior is naturally in accordance with the precepts.

In the context of ordinary human relationships, the ten major precepts help us to know the right state of mind. When we live in a confused and harmful manner, the precepts signal us, through our lack of harmony with them, that we are mistaken in our views and actions and have not yet awakened to our own true nature. The precepts are not a system of “rights” and “wrongs”; they are guidelines providing the illumination that enables us to see where we truly stand.

I would imagine, then, that one could have insight short of complete awakening, in which case one would still need to be mindful of the precepts as rules.

Yes. That is why we work backwards from the precepts, so to speak. Let me explain. With complete awakening, we naturally live our everyday lives in accordance with the truth. However, we live in association with other people, each of us with our own tastes, preferences, and inclinations. Individual differences inevitably give rise to friction between people. This is not a matter of one person being right and another person wrong. What is important, therefore, is maintaining harmony in our relationships, both as individuals and as members of society. The larger the society we live in, the more important it is to have harmony in our behavior toward others. Without this, communal life breaks down.

In this social context, the awakened mind is like a mirror that reflects its surroundings and illuminates the nature of interactions between self and other. But awakening to the true nature of our own minds does not mean that suddenly we can directly affect the world around us. This point is the source of much confusion. Awakening to one’s true self does not confer special powers. An enlightened person is not suddenly able to play the piano like a great musician or paint like Picasso or Mattisse. Painting a picture, composing a song, or writing a poem that will move people’s hearts is a matter of talent and technique, nurtured and polished through practice and effort.

Thus in the spiritual life, awakening must be developed through training, just as great artists train. Such training, in turn, deepens and enriches a person’s character. The mere fact of enlightenment does not mean that all of one’s impulses are suddenly perfect, but rather that one sees more accurately how one should live. When our daily conduct emerges from a clear, awakened mind, then those in contact with us are subtly yet profoundly affected.

The relationship of awakening and daily conduct works in the other direction as well. When one lives in accord with the precepts, one becomes more closely aligned with one’s essential nature. Hence, those who strive to follow the Buddhist precepts will gradually move toward the awakened mind that is manifested by those teachings. This is what I meant earlier when I said that we can work backwards from the precepts.

One must be careful not to misunderstand this, however. A literal, precept-based lifestyle alone is not enough to effect awakening. Following the rules in a mechanical manner can simply be another form of attachment, if it’s not accompanied by effort toward the realization of buddhamind. The precepts can be an effective aid to practice, but clinging to their form is a hindrance.

What we call kensho is an awakening to the absolute liberation that is the original state of our minds, a state we are usually unaware of because of the solid sense of self that arises through our preconceptions, attachments, and desires. Kensho is therefore not something separate from us; it is simply throwing off our fixations, returning to that which we always were. The precepts should serve this goal of awakening.

You mentioned Picasso. Do you make a distinction between a great artist or athlete and someone awakened to the Buddha’s way?

Yes. I was referring to Picasso only as an example of a person of great talent. If art and spirituality were the same, spiritual growth might be easier if we all strove for excellence in art!

Athletes are similar to artists in some ways. Like artists, they start with certain gifts that predispose them to success in their sport, but extraordinary practice and training are also essential if they wish to excel. Through such cultivation, they can attain what can be characterized as states of samadhi [zanmai in Japanese].

There are various types of samadhi. The two main ones are what we call in Japanese ji zanmai [“samadhi of the particular”] and kaio zanmai [“Ocean King samadhi”]. Ji zanmai manifests only in the midst of a certain activity, as the result of absorption in the performance of that activity — like a Japanese go master who, in the course of a game, completely forgets his physical body and the environment around him. Picasso and Matisse, too, undoubtedly painted with such focus, utterly absorbed in their work. This is a state in which body, surroundings, and ethics are all forgotten. Everything is poured into expression. This is how great artists can produce such marvelous works.

Kaio zanmai is much different. It involves a person’s entire being. This is samadhi in the religious sense of the word; it is how the Buddha was liberated. Although there are no “levels” in the experience of enlightenment, Hakuin’s disciple Torei Enji [1721-1792] points out in his “Inexhaustible Lamp” that even after awakening, a long, hard path of further opening, polishing, and purification lies ahead. A single experience of enlightenment does not mark the end of training; continued diligence and effort are necessary for progress in the Way.

Hearing this, beginners may wonder if there’s any use even starting. So teachers tend not to emphasize this aspect of the practice. But the fact is that with kensho, one has only just taken the vital first step toward fulfilling one’s true human potential. From there begins an opening into the world around you.

Ki, the Essence of All Things

In sesshin you often speak about recognizing and regulating ki, or energy, in all parts of our life. This has really helped me. How do you suggest working with ki in zazen?

There are many ways of cultivating ki, such as yoga, qigong, and tai chi. However, the ideal way to cultivate the all-embracing ki that informs our entire being is through zazen. Zazen is a matter of physically experiencing our essential oneness with the very existence of the universe, and it is through this experience that our ki develops. What is most important is that we partake of ki in its universal expression.

We can cultivate ki creatively as we go about our daily lives. Such cultivation-in-action is called dochu no kufu. However, a living practice depends on a thorough grounding in jochu no kufu, the quiet cultivation of seated meditation. There is no basic separation between “passive” and “active,” of course, but those who are unable to partake of universal essence in sitting will not be able to partake of it in action. The fundamental point in zazen is to experience oneself not as a separate, limited body but as the body of the entire universe.

The body itself is central to zazen. When meditating we regulate the body, regulate the breath, and regulate the mind. Ki fills our physical being to overflowing and expands through the breath to an ever-widening circle of our surroundings until it permeates the universe itself. This activation of our universal mind is the true meaning of “regulating the mind” in zazen.

Is this word “ki,” as you are using it, synonymous with buddha-nature?

To know buddhanature is to experience the way in which our wisdom, our consciousness, and our sensation are one with all that exists. “Buddhanature” is simply a word we use to indicate that universal functioning in which the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, body, and especially mind grasp the whole and not just the part. Buddhanature is recognizing the life of buddha in every creature, in every tree and blade of grass.

Ki is our very essence. Lacking ki, we look with our eyes but cannot see. Lacking ki, we think but cannot understand. To embrace and partake of all existence is possible because ki is the essence of all things. From this, too, manifests the wisdom that recognizes buddhanature.

Building a Training Ground in America

Roshi, training is central to any notion of practice, and it’s perhaps best done in a monastic setting. You are creating a monastery in Tahoma, on Whidbey Island near Seattle. What is your vision for this monastery?

The training at Sogenji underlies life at Tahoma. People will find the same essence at both places. Several experienced students from Sogenji are now living at Tahoma, gradually laying the foundations for true monastic training. The dream of opening a fully functioning dojo can’t be realized with a single stroke, so we are taking time, but the inner essence of Tahoma is slowly and surely developing.

Tahoma had a bumpy beginning, but even these difficulties clarified a better approach. The main issue is not so much the physical construction of the monastery as it is the creation of a place of ongoing training even as we build. We do not want to focus only on construction and let the practice go dormant.

I feel very grateful for the steady schedule of daily practice and biannual retreats at Tahoma, thanks to the warm support of the local sangha and the efforts of the Sogenji trainees there. Twenty years of monastic training at Sogenji has made it possible to build Tahoma and to send people to establish dojos in India and Europe. I feel deeply encouraged by this.

Near Tahoma Monastery, you have opened a hospice called Enso House. How did this come about, and what kind of work is Enso House doing?

Before work on Tahoma began, we used to hold our sesshins at a retreat center in the middle of a beautiful forest. One year we arrived to find that the giant trees surrounding this property had been cut down. All that was left was a wasteland of stumps and scarred soil. The scene sent shivers up my spine.

When I asked what had happened, the owner replied that the trees had been sold to Japan. I was shocked to see with my own eyes how quickly an ancient forest could be destroyed for the sake of a little money. It made me wonder who will care for America’s land, who will guide the young? Discussions of these questions inspired the sangha to establish a monastery of our own.

Spiritual growth is not an easy process, however. People start out full of enthusiasm, but as their initial zeal wears off, they often lose sight of the training’s true goals. Many become dissatisfied and turn to other pursuits.

At Sogenji, the retired abbot, Kansei-san, lived out the final part of his existence cared for by the people in training. Zen training is not about personal development or gain. Ultimately, what motivates us in spiritual practice is the realization that as living beings we cannot escape death. Yet as time goes by, even this deep intuition of our own mortality tends to fade amidst the cares and distractions of everyday existence. Our natural tendency is to put

It is critically important, therefore, that practitioners have a concrete sense of their own mortality and of the reality of other people’s deaths. Investigating death, one’s training naturally intensifies and one gains a sense of true direction. Hospice work can be a very genuine form of training. This certainly was my own experience in caring for Kansei-san. The reality of death must not remain conceptual; it has to become part of our practice.

We were looking for a way to provide an opportunity for such practice, so Enso House was established next to Tahoma, with room for about six patients. As a working hospice, Enso House calls on the expertise of trained professionals who help develop the caregiving skills of Tahoma students and volunteers. The professionals, in turn, can gain a deeper sense of their own work through their contact with the devotion of Tahoma students.

In order to help a person through the process of dying, the caregiver should have what might be called an attitude of prayer. A dying person can share this attitude. Without prayer, life is little more than eating, sleeping, and making a living; with prayer, life is illuminated by the light of God. At Enso House, we are trying to provide a place where hospice workers and residents alike can face death with this sense of the sacred.

The sense of the sacred that you’re talking about, is it specifically Buddhist?

It depends upon the person. Those in training at Tahoma are engaged in Zen Buddhist practice, of course, but Enso House residents are of various faiths. The fact of death cuts across religious distinctions. Different religions have their own ideas about the meaning of death. But in the actual process of dying, people of all faiths become one in a spirit of prayerful entrustment. All human beings are equal in this profound act of prayer when facing death.

Zazen in Insecure Times

We live in unsettled and dangerous times. How do you see the work of spiritual people in the world?

During sesshins at Tahoma and in Europe, I see how insecure people are in the world today. People are not aware of this insecurity. They cannot observe what is in their own minds. This, I think, is an indication of the confusion in modern society. People in earlier times had a sense of reverence. We have lost this now, and with it our trust in the future. People are unsure of what their governments are really doing and of where world events are leading them. The economic situation is unstable as well. So there has been a great increase in uncertainty and insecurity from all points of view.

To overcome this insecurity, it is important to understand things in a correct way, or with right view. Inwardly, of course, it is important not to identify with set concepts; outwardly, it is vital that we have full access to accurate information. One encouraging development — one that distinguishes the modern world from former times — is the wider dissemination of news and information. Because governments are run by human beings, they inevitably err. But when they try to limit information about these errors, they engage in a form of mind control. In such cases, it is inevitable that misunderstandings and conflicts arise.

In the old days, the world operated more regionally. This applied to religion as well. The various faiths, like Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism, arose because of regional differences. In the areas where they prevailed, these religions were considered absolute, and the populace was raised in accordance with these absolute teachings. Although Buddhism is regarded as a comparatively tolerant religion, it too was limited in many ways by the cultures in which it developed.

Now, however, it has become possible to liberate religion from limits imposed by regionalism, owing to the greater availability of information and knowledge.

How can zazen enable one to discern what is correct information?

Zazen helps us to free ourselves from notions of profit and loss. If the information we have is accurate, we are able to use it objectively, and not with an eye to our own profit. That is the value of zazen.

So zazen is a way to remove filters and screens.

Yes. As I said earlier, the notions of a self, being, life, and soul are not things that we are born with. They develop later as the result of external influences. The Buddha is not asking us to acquire something we never had. He is simply telling us to return to that which we originally were, before our original nature was covered over. Our social filters are things that develop as we grow up, as devices to help us live and operate within the norms of the culture we are raised in.

There is another aspect of zazen that I think about: the element of alignment, of everything being in its proper place. When you talk about alignment in zazen, I think you mean alignment in things, such as doors or cups, and also with people — how we align ourselves.

Precisely. This sense of alignment deepens through the practice of zazen, which develops our ability to focus. With focus comes an awareness of what in our surroundings is in its proper place and what is not. Ordinarily, people’s minds are full of distracting thoughts and images. As this internal noise gradually dissipates through zazen, a clarity develops that enables us to recognize immediately the “center” of whatever it is we see. For example, when we look at a room, we are naturally aware of its balance point and of how the various objects in the room should relate to it.

How does one find this sense of alignment when there is conflict?

It takes time for that ability to develop. Unlike inanimate objects, people have their individual habits and preferences. Shakyamuni himself had difficulty dealing with this issue and tried various approaches. The “Simile and Parable” chapter of the Lotus Sutra, for example, relates how Shakyamuni resorted to expedient means that on the surface were deceitful but in the larger view helped lead people to liberation.

Several of your students are teachers themselves and have referred to you as a “teacher of teachers.” How do you see your role as a teacher?

[Laughing] Well, I’m not sure I could call myself a teacher of teachers. I’m simply trying to do my best in the position I’ve been placed in, deepening what I have learned and passing it on to as many people as I can.

We can’t afford to concern ourselves solely with our own personal happiness. As I mentioned before, the present era is one of profound insecurity. The social values and the sense of the spiritual that sustained previous generations have lost their meaning for many people. This deep disease is evident even among those in religious vocations. That ordinary people would feel confused is to be expected, given the rapid pace of change in modern times, but the problem is compounded by the fact that so many of the priests and ministers who should be providing guidance are themselves undergoing a crisis of faith, having lost the deep sense of prayer that is the basis of trust in the divine.

I feel that the practice of zazen can awaken us to a deep spiritual foundation through a return to the clear original mind that is ours from the very start. If I can help even one more person to this realization, my efforts will have been fully rewarded.

A last question: when are you moving to the United States?

I’d like to know too! Of course I am planning to come as soon as possible. But my duty as abbot of Sogenji is to find a successor. That is how the Japanese religious system works. I have to take care of this