Zen practice is a return to the ordinary.

It is only in the secular world that Zen is perceived by some as a high and holy practice. The robes are seen as holy, but there is no holiness in Zen. Everything that is done in the temple is of an ordinary nature, including washing dishes, cleaning toilets, mopping floors, cooking, and doing laundry.

The teacher is also ordinary. There is nothing for the teacher to be or show other than the ordinariness of life and how to embrace it. If there is any status thinking and being, that is an inevitable tangling of our worldly views and the path of enlightenment.

For me, a dark-skinned person of African descent, cleaning the temple as Zen practice felt inappropriate and uncomfortable when I was at the beginning of my training. When you are an older black woman and a young white man tells you how to mop the floor during work period, the experience is akin to being a maid or a reminder of slavery. Ordinary temple work is the kind of labor often relegated in this country to folks of color and poor people. It is work that can ensure a lower rank in society.

The memory of my black ancestors and slavery was visceral.

In my early days as a student, I felt the prescribed daily bowing was not for me as a black woman. Because so many of the work leaders were white, in the beginning I could only see the work as what my ancestors did as slaves, sharecroppers, wet-nurses, and maids. The memory of my black ancestors and slavery was visceral.

Of course, Zen students of many ethnicities were also working. Did their experience remind them, as it reminded me, of oppressive conditions of labor? Did women feel they were just continuing what folks call “women’s work”? Were there immigrants who felt they were doing menial work imposed on them because they were not considered citizens?

On the other hand, did the white male students feel the work was beneath them? That, I believe, was traditionally the point of work practice in Zen temples. Part of Zen practice is to recognize the consciousness of superiority and inferiority, the dangerous explosive line between “us” and “them.” The temple experience of young Japanese men was intended to humble and prepare them to take on jobs and families in the world. But as the prescribed work of Japanese Zen temples was passed on to white American practitioners, did they consider that the cultural context of the practice would change as different folk embraced the Buddha Way?

Many people of color, and especially black people, come to Zen practice with unavoidable past experiences of strenuous and demeaning work. In essence, they have done the work long before they arrive. In fact, they have overworked to survive blatant discrimination and rejection.

For those who suffer from internalized “isms” like racism and sexism, to be humbled by spiritual practice is counter to their task of wellness and healing from dehumanization. If anything, they are looking to emerge from the place of submission. They are looking for a place to speak rather than be silent, to communicate the suffering of all “isms” being played out while sweeping the temple’s floor.

Yet, I stayed with Zen practice, doing the mundane, and years later I scrubbed the toilets when I was head student, in order, they say, to remain humble. The more I bowed, the more I scrubbed. Eventually, I felt my ancestors moving my body, back and forth. They told me this work was good. I was skeptical.

Me: “Really? I don’t need this.”

Ancestors: “Exactly. You feel you have become better than us.”

Me: “I went to school because you said education was the best thing for black people. I got a Ph.D. so I don’t need to do what black folks have always done.”

Ancestors: “Your pride is no good to us. Your degree is no good to us. We need your heart to be healed. Don’t let intellect take the place of love. You must love more.”

I swept longer, breathing, listening, crying. This is true, I say to myself.

Me: “But I worked so hard not to be oppressed as you were. I worked for justice. I prayed. I ate well. I did good deeds most of my life.”

Ancestors: “We need more than that from you. We don’t need you to be a good Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, follower of African Orishas, or whatever. We need you to remember the dust from which you came. We need you to remember a time before things went crazy, when they sold Africans like us. There was something before. It is still hidden from you. Find it. Keep sweeping—not to clean but to see and hear where your heart is blocked from what we see for you. We put you in a place where you would be bothered enough to change.”

What would Zen training (not just temple cleaning) look like for those who come from a lineage of ancestors who were mistreated and exploited? Mistreatment in the past will create mistreatment in the future, even within our spiritual sanctuaries, if we are not aware of such a consciousness within all of us.

If ancestral memory of slavery arises in our practice, as it might for dharma practitioners of African descent, it must be acknowledged and used to open our eyes to the consciousness of hatred. If we ignore what is stored in any of us, then how can we know what paths we have already suffered?

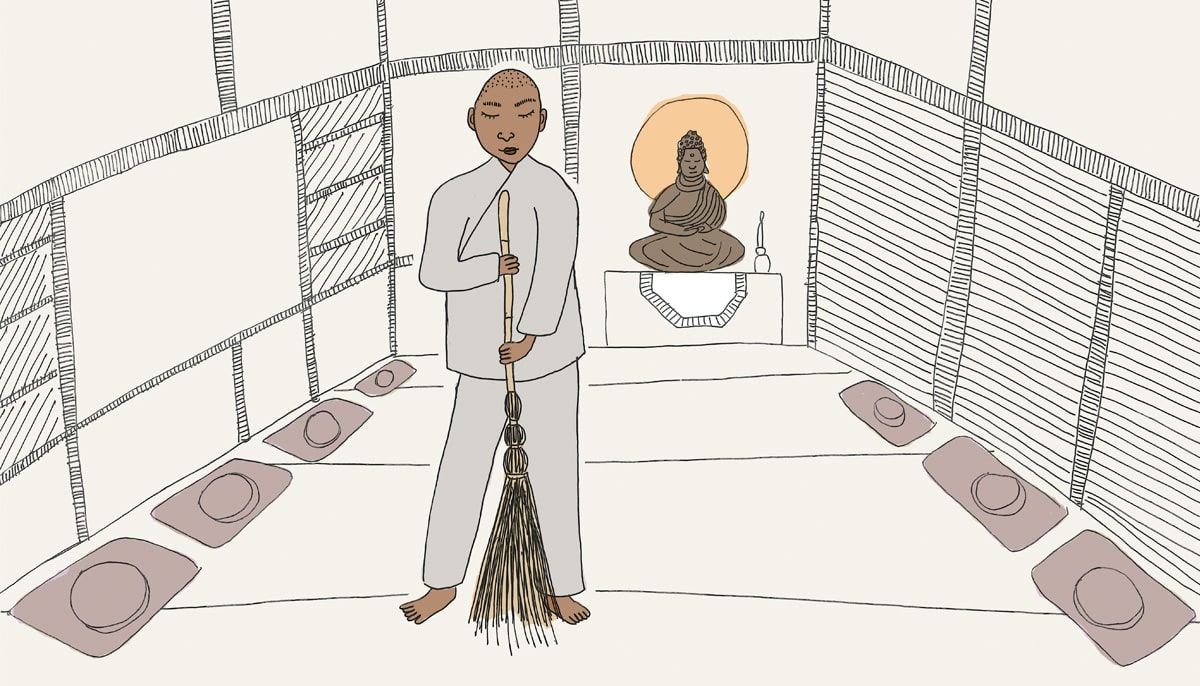

I know that temple cleaning is the motion arising from sitting meditation, not history repeating itself.

Today when I clean the temple, I know it is my ancestors calling. I know that the memory within me of their existence as slaves is being understood and transformed. I know that temple cleaning is the motion arising from sitting meditation, not history repeating itself.

If I am fortunate enough to be offered a chance to sweep, it is a profound time with my own heart—to use the broom as a ritual connecting this life and the lives of those in my past. I am not replicating what my ancestors did as slaves. On the contrary, they have brought me to this moment. How else would I appear in such a temple?

In sweeping, I had to climb down from who I thought I had become. The practice was to move beyond easily-accessed, well-served black pride into seeing the ways I suffer. I began to see the ascendance from enslaved Africans as a sanctioned and gifted walk toward the very liberation the Buddha spoke of, and what the ancestors saw for me and everyone else. While economic reparation for enslavement is true and relative justice, the ultimate reparation is true freedom from the poison of our oppression. We need both.