I Take Refuge in the Buddha

There isn’t just one Buddha, says Mushim Patricia Ikeda. The Buddha is awakened mind.

When most people think of the Buddha, it’s Siddhartha Gautama they picture: the prince, who it is said, was born 2,600 years ago in Nepal, grew up to attain enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree, and then went on to teach the path of awakening for forty-five years. But this “historical” Buddha is just one aspect of what is meant when we say, “take refuge in the Buddha.”

“Buddha” means “awakened being,” and according to traditional Buddhist cosmology there are countless buddhas constantly manifesting in the trichiliocosm or multiverse. Theoretically, a fully awakened or enlightened being is one in which the roots of greed (clinging, craving), hatred (aversion, harbored anger), and ignorance (delusion and separation) have been permanently eradicated. Taking refuge in Buddha means committing to having faith in buddha mind—awakened mind, big mind.

To say, “I go for refuge in (or to) Buddha” is a declaration of faith. When I teach Buddhism for beginners, I say that Buddhism is a global faith tradition and may or may not be called a global religion because Buddhism is nontheistic. It is neither for nor against belief in a creator God or gods. There are many Christian, Jewish, and atheist Buddhists.

So, what does it mean to have faith in the Buddha? Many years ago, my great spiritual friend Ven. Bhante Suhita Dharma and I several times co-taught the annual people of color meditation retreat at Vallecitos Mountain Retreat Center in New Mexico. Once, while giving a dharma talk, Bhante shared that he’d been a Trappist monk as a young teenager and before that a star altar boy in Texas. He said he still considered himself a Catholic.

In the question and answer period that followed, a woman raised her hand and said, “I’m so confused! What do you do if you want to meditate, and what do you do if you want to pray?”

Bhante Suhita considered this in relaxed silence, then he replied, “When I feel like meditating, I meditate. When I feel like praying, I pray.”

Thus, having faith in Buddha—taking refuge in Buddha as many awakened beings and awakened mind and the central myth of Prince Siddhartha—is not exclusive.

Also, bear in mind that buddhas don’t suddenly manifest and cure terminally ill people or feed starving people, at least not in my world. So, what exactly does taking refuge in the Buddha do for me, really?

As Shantideva, a renowned eighth-century Buddhist philosopher said, “The Buddhas do not wash unwholesome deeds away with water, nor do they remove the sufferings of beings with their hands, neither do they transplant their own realization into others. It is by teaching the truth of suchness that they liberate (beings).”

I first heard a version of this quotation as a poignant voiceover by the actor playing the young Dalai Lama in a scene in the 1997 movie Kundun. An epic film directed by Martin Scorsese, it depicts the 1951 invasion of Tibet by the Chinese and the death, cultural destruction, and imprisonment of many Tibetan Buddhist people.

The history of the world—and the present—is full of such violence and suffering. Plus, today, with killing heat caused by the climate crisis, we are, quite literally, on fire. I do not know what will save us.

Still, we have to do something. The Buddha needs to take refuge in us for us to take refuge in the Buddha. My understanding of “refuge” is not a bombproof bunker with climate control. Instead, it’s refuge in the sense of “nature refuge,” an area in which shortsighted beings aren’t allowed to interfere with the natural life of the native animals, plants, insects, and birds.

A refuge is an area in which beings are born, live, die, fight, and eat one another, but without arguing over religions and nationalities or destroying the earth or bodies of fresh and salt water. Bodies of water. Earth in the sense of soil, ground, and planet is also a body or many bodies, the fecund source of everything that we are.

The tension-filled Korean Demilitarized Zone (the DMZ) divides North and South Korea. With its heavily fortified fences, landmines, and listening posts, the zone is uninhabited by humans. So, although the DMZ is only seventy years old and 160 miles long and 2.5 miles wide, it has become a wildlife refuge, home to more than one hundred endangered animal species, plus many endangered plants. I think of the rare red-crowned cranes and Siberian tigers raising their young amidst endangered plants and trees, taking and making refuge for life to flourish in a tiny strip of land filled with land mines. It’s the habitat they have, and they’re going about their business of making it habitable.

When my son was little, I used to say, “We live on a planet called Earth Buddha.” He said, “This is why we are here, to protect Earth Buddha with all our thoughts of love.” Now that he is an adult, he and I know that thoughts of love need to lead to acts of love, and acts of love need to be informed by strategic wisdom. They need to be politically savvy to not waste our precious time and money. I’m determined to do what I can in the time I have left—to keep making and taking refuge in Buddha until the great work is done.

I Take Refuge in the Dharma

Rebecca Li explains how the Buddha’s teachings are a roadmap to less suffering, more happiness.

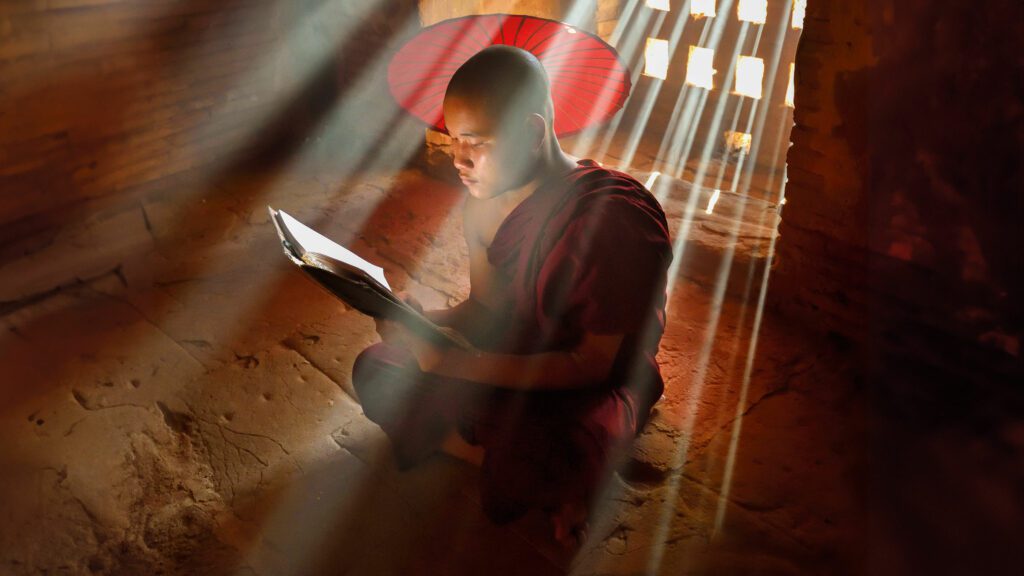

The second dharma jewel is the Buddha’s teachings—teachings that free us from suffering and enable us to find happiness and fulfillment. These teachings include precepts that guide us to live ethically, meditation methods that cultivate mindfulness, and approaches to living that cultivate wisdom.

Shakyamuni Buddha taught that we need not suffer, even when life is challenging owing to illness, aging, death, being separated from what or who we love, not getting what we want, or being stuck with what we dislike. He taught that it’s our entrenched habit of reacting to life situations with aversion, or with craving for the moment to be other than it is, that causes suffering. When we see that each moment is the manifestation of the coming together of causes and conditions, and that change is inevitable, we can experience the present moment as it is. For instance, physical discomfort owing to sickness or aging can be experienced as changing bodily sensations. Understanding and realizing that sensory experiences are inherent to being alive with a body, the urge to react with aversion can be released. When the present moment is experienced as it is, there may be physical discomfort, but there’s no suffering.

Similarly, through the meditative practice of cultivating moment-to-moment clear awareness, we realize that we’re truly interconnected. It becomes clear that we cocreate each other and the world. Our circumstances are the result of everyone’s actions, and our actions affect others, whether we intend for them to or not. Innumerable causes and conditions affect each of us, our actions, and the results of those actions. With this realization, we can accept changes in our circumstances with equanimity instead of reacting with aversion and generating suffering.

It also becomes clear that when we suffer, we’re more prone to cause harm to others, often to those we love dearly. Clearly aware of the effects of our actions, we commit to putting the dharma into practice to reduce our suffering, which in turn helps us cause less harm, be more fully present with people, and to see their full humanity. Furthermore, we’re more capable of recognizing and taking responsibility for our mistakes and identifying and taking appropriate actions to rectify them. In other words, putting the Buddha’s teachings into practice frees us from suffering and enables us to function in the world with more wisdom and compassion.

Taking refuge in dharma means that we commit to putting dharma into practice in all situations, regardless of what’s happening, whether things are going well or not. This means maintaining moment-to-moment clear awareness of body/mind in this space and committing to work with ourselves gently to reconnect with dharma practice when we find we’ve reverted to our entrenched habit of suffering—and to do so over and over again with patience and kindness.

Engaging with the Buddha’s teachings in this way is to allow every aspect of our life to be transformed. For many of us, even when things are largely going well, we find ourselves suffering with a sense of unsatisfactoriness owing to the habit of focusing on one thing that we’ve labeled as problematic, bad, or undesirable. The entrenched habitual reactivity of aversion compels us to try to get rid of it, run away from it, or be in denial, rendering ourselves unable to be at ease with each emerging present moment as it is. Meanwhile, we forget that every moment is brand new, and we ignore everything that’s going well and everyone who supports and cares about us, causing them to feel unseen and unappreciated. Taking refuge in dharma reminds us to reflect on how we cause ourselves suffering and to remember to put the teachings into practice. Taking refuge in dharma is a way of living that reduces suffering, creates a sense of connection, and brings clarity, meaning, and a sense of wonder to our lives.

A practitioner shared with me that she used to get stressed out when she went home, expecting that she’d have to clean up mess left by her husband while she was away. Having committed to practice in all situations and to cultivate clear awareness, she realized that she tended to focus only on the dirty socks left on the floor, which led her to feel the house was a disaster, which triggered habitual reactivities of compulsive cleaning, anger, and resentment.

By opening her awareness to the entirety of the moment, including her own habitual reactivity, she was able to see that the house was fine; there was no disaster despite some items on the floor.

She realized that her suffering was caused by her habit of thinking of her husband only as “the messy guy,” which blocked her from recognizing all the moments when he was attentive, supportive, picked up after himself, and looked after everyone at home while she was away.

Remembering that every moment is the coming together of causes and conditions, she realized that her husband and children had been doing quite a bit to keep the house clean and that she’d taken their contributions for granted and had never expressed any appreciation. She was also able to realize that their effort constituted the causes and conditions that made it possible for her to spend a week away on retreat. Opening her awareness to include all that made her life possible, she found her heart filling with gratitude. She was deeply touched by the love and care of her family members and saw clearly how hurtful her harsh criticism had been to them despite her good intentions.

By doing her best to maintain full presence in every situation, this practitioner now appreciates her family’s full humanity and respects them for who they are, not who she thinks they’re supposed to be, and her life has been transformed. Home is no longer a place that brings resentment and dread, where everyone is a problem to fix. Instead, it’s a place where she and her loved ones cocreate each other and their lives together. She’s clear that every moment she remembers to practice the dharma, there’s less suffering and more kindness and clarity, benefiting herself and everyone she encounters. The socks occasionally left on the floor no longer bother her. When they do, she’s grateful for the opportunity to practice recognizing and releasing her habitual reactivities.

As she continues to bring her practice into her workplace and other situations, she becomes more at ease and confident in her ability to face life’s challenges. Even in the most trying situations, she feels her heart filled with dharma joy. Less consumed by suffering, her energy is freed up to help others in need—not by martyring herself to make everyone happy, but rather by responding to the needs of others, while also taking her own present circumstances into account. Slowly but surely, she’s treading the Buddha’s path to live a life of wisdom and compassion. She is taking refuge in dharma.

I Take Refuge in the Sangha

In community, we grow together, says Rev. Blayne Higa. We give care. We receive care.

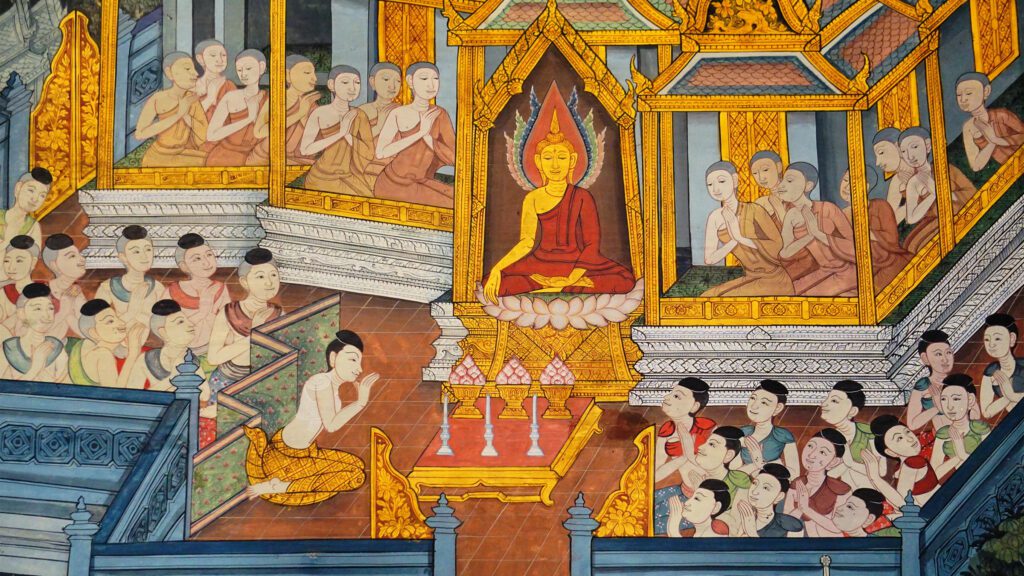

A sangha is a values-based community of practice grounded in the Buddha’s teachings. It’s a refuge in this world of suffering, where the path of spiritual liberation can be actualized. Sangha is one of the three jewels of Buddhism, because it is where the living dharma is embodied in the very lives of its members.

Traditionally, sangha referred to the monastic community of the Buddha’s disciples, but over time it expanded to include lay followers, the communities in which we live, and sometimes even all of nature itself. This broader meaning of sangha is foundational in the Jodo Shinshu tradition of Pure Land Buddhism. As a nonmonastic householder path, Shin Buddhism, as it’s known in the West, is an inclusive path of awakening.

Shinran Shonin (1173–1263), the founder of Shin Buddhism, writes in the Kyogyoshinsho (True Teaching, Practice, and Realization), “In reflecting on the ocean of great shinjin [entrusting heart], I realize that there is no discrimination between noble and humble or black-robed monks and white-clothed laity, no differentiation between man and woman, old and young.” This radical inclusivity led Jodo Shinshu to become the most popular tradition in Japan, which in turn is why it is one of the oldest Buddhist traditions in America, having been brought by Japanese immigrants in the late 1800s.

Since their establishment, Shin Buddhist sanghas have always been communities of care serving as a refuge from the harsh realities of immigrant life in America. They were communities where people shared the joys and struggles of life together. Where culture and religion were preserved and celebrated, free from discrimination and the bigotry of anti-immigrant sentiment. This is why Japanese American Buddhist temples were closed and their priests and members were forcibly rounded up and imprisoned during World War II. Despite these injustices and hardships, the unshakable spirit of sangha endured and flourished in the camps and after. Even today, Shin Buddhist sanghas continue this tradition of care and welcome for all who seek refuge.

A fundamental characteristic of Shin Buddhism is the spirit of ondobo ondogyo. It means that all who share the aspiration for enlightenment are fellow travelers, journeying together on the path of dharma. Each of us is a good spiritual friend, teacher, and guide to one another. In this way, sangha becomes the living expression of our profound connection and where an intimate togetherness is realized.

We live, work, cry, and celebrate together as a community of fellow travelers, and we realize that when one of us stumbles and falls, we all do, because we are connected. This is why we have a shared responsibility to care for one another. Just as a bodhisattva makes vows to forsake their own awakening for the liberation of others, we live with a spirit of joyful service and sacrifice for mutual benefit and care.

The Covid-19 pandemic was an opportunity for learning the true meaning of sangha. During the height of the lockdown, several volunteers quickly organized a phone tree and began calling our sangha members to check in and offer a friendly voice. This was particularly meaningful for many of our elders who live alone and who are not comfortable with technology. The sound of a human voice facilitated the healing power of connection and reaffirmed the significance of being in community.

Prioritizing basic needs, we also began a food-box program, which was led by our younger members. Several times during that first year, a small group of volunteers wearing masks and gloves packed boxes of food that were distributed to members of our sangha. Each time, over a hundred boxes filled with produce, bread, eggs, tofu, frozen chicken thighs, and other foodstuff were assembled. As people drove up to the temple social hall, our volunteers loaded each car with a box. Several folks kindly picked up boxes for friends and neighbors unable to drive, and our volunteers made deliveries to the rest. As word spread, the outpouring of support was truly amazing. Several sangha members donated bananas, avocados, and papayas from their home gardens; some gave homemade pickled vegetables, while others baked hundreds of cookies and manju (a Japanese pastry) that were all gratefully shared. This is what it means to be a sangha—to share in the fullness of life as spiritual friends within a community of care.

The Buddha taught that good friendship is the whole of the spiritual life. Affirming its importance, Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi reflects, “Good friendship is essential not only because it benefits us in times of trouble, satisfies our social instincts, and enlarges our sphere of concern from the self to others. It is critical because good friendship plants in us the sense of discretion, the ability to distinguish between good and bad, right and wrong, and to choose the honorable over the expedient.”

Every day as I care for sangha, my understanding of good spiritual friendship deepens. I am continually enriched and transformed by the sangha. Because our spiritual community is grounded in the Buddha’s teaching, we live and act inspired by wisdom unfolding as compassion. Sangha is a refuge where—together as spiritual friends—we grow in the dharma. Rennyo Shonin (1415–1499), a descendant of Shinran and the eighth spiritual leader of Jodo Shinshu, advised his followers, “You lose nothing when you make friends with devout Buddhists. Even if they do strange things or crack jokes, they have the buddhadharma deep in their hearts; in befriending them, you will gain much benefit. So it is said.”

Good friendship is indeed the whole of the spiritual life. Living and learning within a community of fellow travelers is the practice. Sangha is the way.