Steve Silberman reviews “Crowded by Beauty: The Life and Zen of Poet Philip Whalen,” by David Schneider.

On October 7, 1955, one of the most celebrated poetry readings in American history took place at the Six Gallery in San Francisco. The long, narrow exhibition hall, located in a converted auto-repair shop in the city’s Marina district, was jammed with young writers and artists drawn by postcards mailed out in the preceding weeks, promising “new straightforward writing… remarkable collection of angels on one stage… charming event.” The emcee was poet Kenneth Rexroth, and the undisputed highlight of the event was the impassioned debut of a poem called “Howl” by a young poet named Allen Ginsberg, with Jack Kerouac in the audience slapping the sides of a wine jug and shouting, “Go!”

Of the five poets on the bill that night, three became famous, elevating the Beat Generation (the name that Kerouac coined for his group of gifted friends) to local—and eventually global—prominence. The following morning, Ginsberg received a telegram from City Lights Books publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti that read, “I greet you at the beginning of a great career. When do I get the manuscript?” Gary Snyder went on to forge an incisive poetic amalgam of ecological awareness of place and Zen insight into the interdependent nature of existence that would earn him a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Michael McClure, the youngest writer in the group, would become a boldly inventive and fearlessly controversial poet and playwright in his own right.

The fourth “angel,” Philip Lamantia, is primarily remembered in Beat circles as a virtuoso of surrealism in English. But what of the fifth reader—a bookish, moon-faced, former Army radio technician from rural Oregon named Philip Whalen?

In many ways, Whalen was not like the others. In a group of wiry, strikingly handsome young men, he was decidedly pear-shaped and already seemed middle-aged, though he was still in his early thirties. The other poets had aspirations to be alpha males, but Whalen could seem nearly feminine or maternal, as if he was channeling the female muses whom he frequently called to his aid in his work. “Straightforward” was not quite the word for his writing; instead, his poems rambled affably among disparate kinds of material, often in multiple languages. While Kerouac and Ginsberg cultivated very public voices, Whalen’s language was so personal, idiosyncratic, and even cranky that it could seem hermetic. One of the poems he read that night (“Plus Ça Change”) was improbably written from the point of view of a married couple gradually metamorphosing into birds:

Listen. Whatever we do from here on out

Let’s for God’s sake not look at each other.

Keep our eyes shut and the lights turned off—

We won’t mind touching if we don’t have to see.

Two years later, Whalen would declare in a poem, “This poetry is a graph or picture of a mind moving.” By describing the topography of his own consciousness, he hoped to produce maps of ephemeral internal states that might be useful for others. Or not. Unlike most of his Beat compatriots, Whalen didn’t seem to care much if his poems were even read. The primary pleasure of his work was in the craft itself.

As a result, while innumerable biographies and volumes of commentary have been churned out about Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Snyder, the Beat spotlight rarely lingers on Whalen, who is typically cast as a kind of benevolently plump supporting character. In Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, he appears as Ben Fagan, a “quiet respectable booboo… smiling over books,” who patiently sits beside the author in the park for an entire afternoon, sweetly watching over him as he sleeps off one of his alcoholic blackouts.

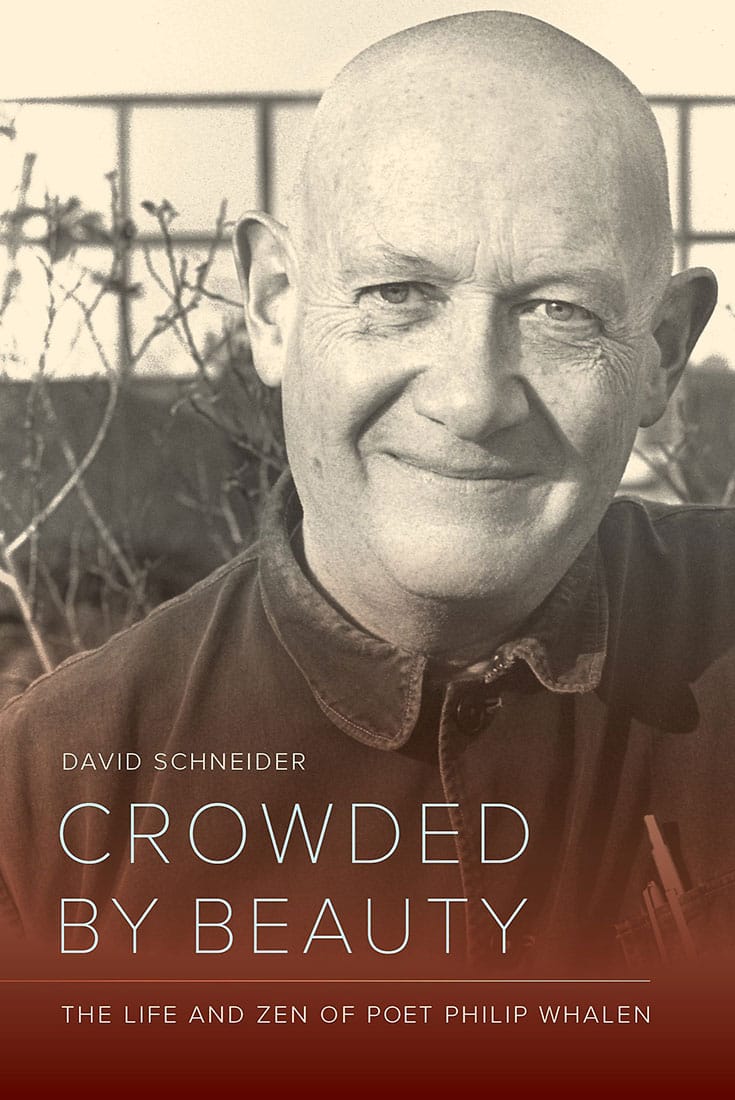

With the publication of David Schneider’s biography, Crowded by Beauty: The Life and Zen of Poet Philip Whalen, however, the original dharma bum finally gets the sustained attention he deserves. It is not only one of the most keenly observed books on the Beats ever published, but it’s also a fascinating exploration of the life and dharma of one of the first American-born Zen teachers.

In typically self-effacing fashion, Whalen never assembled a collection of his thoughts on Zen outside of his poetry, and he rarely saw to it that his talks at Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco, where he served as abbot in the early 1990s, were recorded. But without his quietly pervasive influence, Buddhism might never have taken root in American soil so vigorously and spread so prolifically. While they were students living together at Reed College in Oregon, Whalen introduced Snyder and another young poet, Lew Welch, to Asian philosophy and literature that was steeped in Buddhist perceptions, including the classic haiku collections translated by R.H. Blyth.

Kerouac often gets the credit for putting a generation of peripatetic seekers on the cushion, but daily meditation practice was never his strong suit. Whalen and Snyder, however, had already committed themselves to Buddhism as a physical, embodied activity (rather than just a philosophy) before the Six Gallery reading, discovering in zazen a method for drilling down to deeper strata of consciousness than even poetry was able to reach. They began sitting together in their flat on Montgomery Street in the early 1950s.

After the reading and the subsequent obscenity trial that thrust “Howl” and the Beats onto the world stage, instead of cultivating his notoriety as a poet, Whalen followed Snyder to Japan to study Zen in the traditional way. They also kept Ginsberg, who had adopted them as his spiritual advisors, grounded as he toured the globe searching for gurus and holy men who could give him a mystic fix. “Ginsberg sailed out on truly brave explorations of mind and consciousness,” Schneider observes, “counting on Whalen and Snyder as the sane Buddhist shore upon which he could drag his psychic dory, there to receive calm but hip instruction.”

Expat life in Kyoto, even with its myriad hardships and bafflements, had a tonic effect on Whalen’s poetry. He composed his most sprawling work there, Scenes of Life at the Capital, a book-length poem that encompassed notes of his travels around the city, news reports, scraps of history, ideograms and doodles, and obscure words that tickled his mind’s ear, like bezoar and curcurbite. Instead of a popular poet, he became a poet’s poet—an artist whose work gave other artists permission to blow as deep as they wanted to blow, as Kerouac put it.

Schneider is forthright about the practical challenges that Whalen faced in trying to survive as a poet who could not abide holding a day job to pay the rent. “A real writer or thinker shouldn’t have to work anyway!” he would complain to Snyder (which, as Schneider points out, isn’t quite the Zen attitude of “a day without work is a day without food”). It’s a bit painful to read about Whalen living in penury for most of his life, unable to afford a new pair of shoes much less the fattening delicacies he was always hankering after, depending on the kindness of strangers and the forbearance of friends, sleeping in borrowed beds until the pleasures of his erudite conversation ran thin.

After a couple of decades of this, the invitation from an old friend from poetry circles—Richard Baker, another American Zen student who trained in Japan and became Shunryu Suzuki Roshi’s dharma heir—to take up residence at San Francisco Zen Center, where Baker was the abbot, must have come as a relief, even if Whalen quickly resumed complaining about feeling exhausted by the daily schedule (which he was not, in fact, obliged to follow). Even so, Whalen was committed to “do the Buddhism right,” as he put it, and threw himself into the role of being a “professional” meditator with wholehearted effort, getting up for predawn zazen and bearing down for sesshin even when his health was frail, as it increasingly was.

Whalen did the Buddhism right, even when that entailed following his teacher to Santa Fe—far from his beloved Pacific Ocean and the ever-beckoning chow fun parlors of Chinatown—after Zen Center was thrown into chaos by the revelation of Baker’s love affair with the wife of a major supporter of the sangha, followed by several similar revelations involving students and his subsequent removal as abbot by the Zen Center board.

Whalen tried to make the best of living in an arid environment that abraded his skin and aggravated his asthma, but then eagerly accepted an assignment to return to the Bay Area to become the head of practice at Hartford Street, a combination temple and hospice in the heart of San Francisco’s Castro district, which was hit hard by the AIDS epidemic. (Disclosure: I was Whalen’s personal assistant at Hartford Street for five months in 1993 and kept an online journal of that time; the title of Schneider’s book is taken from a remark that Whalen made to me: “I will be crowded by beauty till I die.”)

Whalen eventually received dharma transmission from Baker Roshi and assumed the abbotship at Hartford Street. His talk at the Mountain Seat ceremony in which he was installed was brief and overwhelmingly to the point. “This seat is empty. There is no one sitting here,” he said. “Please take care of yourselves.”

Schneider’s own lifetime of experience as a practitioner (he is a former student at the San Francisco Zen Center, an acharya in the Shambhala lineage, and currently the head of Shambhala Europe) gives him an intimate perspective on the evolution of Whalen’s practice, his fraught relationship with Baker Roshi, and the dynamics of the multiple sanghas in which it all unfolded. Schneider’s training also enables him to say very complex things simply, nowhere more strikingly than in the two-word sentence that concludes his description of Whalen’s Mountain Seat ceremony: “When he said, ‘There is no one sitting here,’ it was not an admission of ignorance. He’d looked.”

Was Whalen a poet with a meditation habit or a monk with a writing habit? As his eyesight dimmed in old age, the monk seemed to gain the upper hand, and his writing became both less frequent and more concise. “His quirks became his pointers,” wrote Snyder, “and his frailties his teaching method.” Schneider chronicles Whalen jitterbugging and scat-singing during an oryoki service in the zendo, and passing Lifesavers and lemon drops down the row of young monks sitting tangaryo, the grueling week of virtually nonstop sitting required to enter Tassajara monastery.

If this was not the type of behavior that one expects from a high-ranking member of a temple hierarchy, it had the unmistakable flavor of bodhisattvic activity. Though Whalen fit no one’s cookie-cutter idea of what a Buddhist cleric was supposed to be like, he pointed directly to the nature of mind all his life, both in word and in deed. Crowded by Beauty captures this elusive vocation by presenting him with his frailties intact.

“Those who loved him, hung out with him, practiced and studied under his guidance, would not for the most part call him their ‘Zen master,’” Schneider concludes. “Every one of them would say, however, that Philip was teaching them something, that he was a master of something, and that they were getting it from him.”