During the war with the French, Thay had contracted malaria and dysentery, and, during this trip to the remote mountain areas, both diseases recurred. Despite that his presence was very inspiring for our whole team. Thay reminded us to be mindful of everything—the way Thay Nhu Van, a high monk who was very popular with both sides, talked to the officers of both sides; the way Thay Nhu Hue organized the local Buddhists; and the way the rowers of our boat ate in mindfulness. We observed the steep canyon of the Thu Bon River and were aware of the icy mountain wind and the homeless victims of the flood on the verge of death. The atmosphere of death permeated our whole trip—not only the death of flood victims, but also our own risk of dying at any moment in the ever-present cross fire.

As we were leaving the area, many young mothers followed us, pleading with us to take their babies, because they were not certain the babies could survive until our next rescue mission. We cried, but we could not take these babies with us. That image has stayed with me to this day.

After that, as I went to Hue every two months to lecture on biology, I never failed to organize groups of students, monks, and nuns to help people suffering in these remote areas. We began with the daylong journey from Hue to Da Nang, where we would sleep in a temple and then travel to Quang Nam and Hoi An. In Hoi An, we rented five midsize boats to carry nearly ten tons of rice, beans, cooking utensils, used clothing, and medical supplies.

If we die in service, we can die with a smile, without fear.

One night, we stopped in Son Khuong, a remote village where the fighting was especially fierce. As we were about to go to sleep in our boat, we suddenly heard shooting, then screaming, then shooting again. The young people in our group were seized with panic, and a few young men jumped into the river to avoid the bullets. I sat quietly in the boat with two nuns and breathed consciously to calm myself. Seeing us so calm, everyone stopped panicking, and we quietly chanted the Heart Sutra, concentrating deeply on this powerful chant. For a while, we didn’t hear any bullets. I don’t know if they actually stopped or not. The day after, I shared my strong belief with my coworkers, “When we work to help people, the bullets have to avoid us, because we can never avoid the bullets. When we have good will and great love, when our only aim is to help those in distress, I believe that there is a kind of magnetism, the energy of goodness that protects us from being hit by the bullets. We only need to be serene. Then, even if a bullet hits us, we can accept it calmly, knowing that everyone has to die one day. If we die in service, we can die with a smile, without fear.”

Two months later, while on another rescue trip, bombs had just fallen as we arrived at a very remote hamlet, about fifteen kilometers from Son Khuong Village. There were dead and wounded people everywhere. We used all the bandages and medicine we had. I remember so vividly carrying a bleeding baby back to the boat in order to clean her wounds and do whatever surgery might be necessary. I cannot describe how painful and desperate it was to carry a baby covered with blood, her sobbing mother walking beside me, both of us unsure if we could save the child.

Two years later, when I went to the United States to explain the suffering of the Vietnamese people and to plead for peace in Vietnam, I saw a woman on television carrying a wounded baby covered with blood, and suddenly I understood how the American people could continue to support the fighting and bombing.

The scene on the television was quite different from the reality of having a bleeding baby in my arms. My despair was intense, but the scene on television looked like a performance. I realized that there was no connection between experiencing the actual event and watching it on the TV screen while sitting at home in peace and safety. People could watch such horrible scenes on TV and still go about their daily business—eating, dancing, playing with children, having conversations. After an encounter with such suffering, desperation filled my every cell. These people were human beings like me; why did they have to suffer so? Questions like these burned inside me and, at the same time, inspired me to continue my work with serene determination. Realizing how fortunate I was compared to those living under the bombs helped dissolve any anger or suffering in me, and I was committed to keep doing my best to help them without fear.

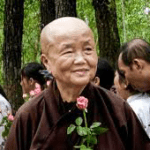

Excerpted from Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War by Sister Chang Khong. © 2007 Unified Buddhist Church. Reprinted with permission of Parallax Press.