The practice of illusory body is the second practice of the Six Dharmas, in each of the different configurations compiled by Naropa, Niguma, and Sukkhasiddhi. The Tibetan term is gyulu; gyu translates as illusory and lu as body. The Sanskrit equivalent of gyu is maya. Both of these translations point to the playful dance of appearances that, though we perceive them to be solid, real, and existent, are in actuality rainbow-like. Due to particular causes and conditions, they appear, yet upon closer examination, we can see that they lack inherent existence.

Not being aware of the illusory nature of everything in our experience is a source of great suffering; when we begin to wake up to the true nature of things, we come to experience the creative, magical qualities of this illusory nature. On a mundane level, we refer to magicians as illusionists who delight us with their sleight of hand. In the context of illusory body practice, we can delight as we explore how we magically and creatively project a world of self and other that we otherwise habitually perceive as real and solid. We can further refine our skills such that we become master illusionists who see the rainbow-like nature of all, and who can even manipulate and manifest energy as form in a way that supports and benefits others.

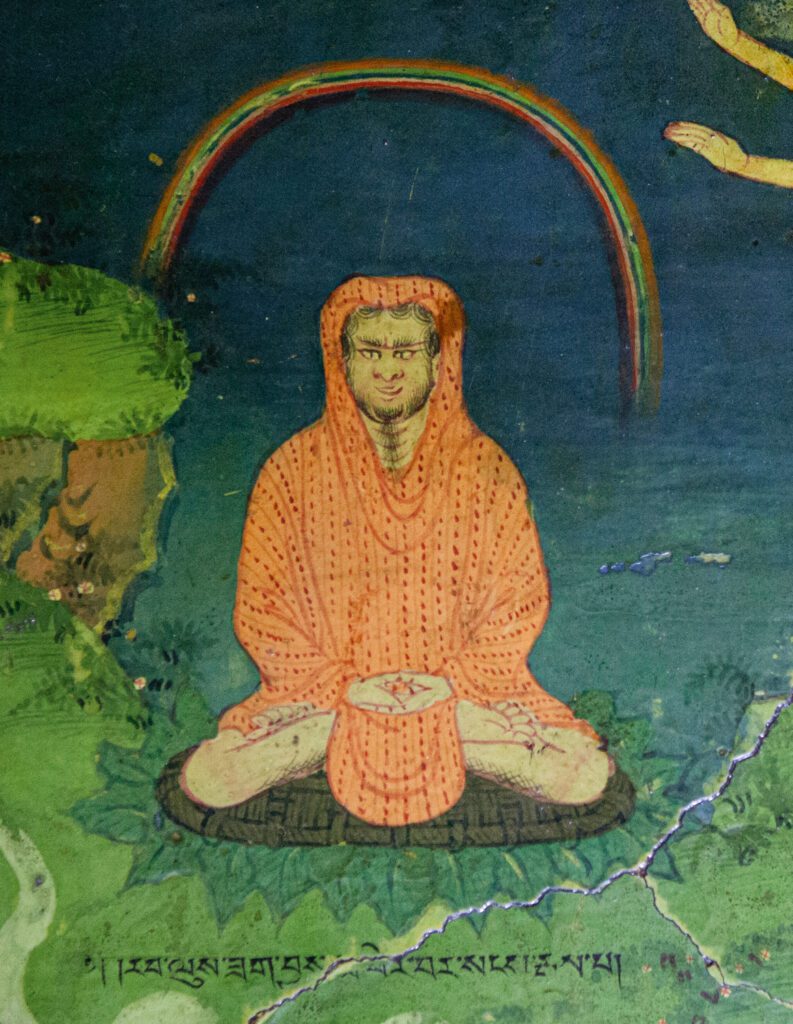

Vajrayana, or tantric practice, includes two stages: the generation/creation stage and the completion stage. In the creation stage, we work with a yidam (an embodiment of an awakened quality) such as Chenrezig, who is the embodiment of compassion. We experience the yidam as arising in a form subtler than our coarse human body: an extremely subtle body of light, appearing like a rainbow—apparent yet transparent and ungraspable, even as we visualize them in front of us.

In the creation stage, we imagine ourselves to be and act as if we are the yidam, arising in an extremely subtle body of light. We engage a sacred outlook whereby we visualize our world as a pure realm within which all beings are also the yidam. We familiarize ourselves with visualizing our coarse body as the extremely subtle body of the yidam. We work to experience our speech and all sound as the sacred mantra of the yidam, and to experience our mind as the awakened mind of the yidam. We aim to purify our ordinary experience of body, speech, and mind, as well as all aspects and stages of our life cycle. We act as if we are enlightened as a means to unveil our ever-present and fully developed buddhanature.

Over the course of the practice, we come to genuinely recognize that all that we experience is sacred and inseparable from emptiness. We perceive all phenomena as the radiant luminosity of awakened mind. All form is experienced as appearance and emptiness arising simultaneously. Likewise, all sound is recognized as co-emergent sound and emptiness, and all movement of mind as co-emergent awareness and emptiness.

What if our mistaken perception of a solid world of self and other could give way to a recognition that all we experience is a magical, rainbow-like, miraculous dance of awakened mind that we have the capacity to participate consciously in creating?

The Six Dharmas, including illusory body practice, are completion stage practices. In contrast to the creation stage, in which we experience arising as the yidam, the completion stage involves actualizing this aim through various techniques that work with the subtle body, which comprises the channels (Sanskrit: nadi; Tibetan: tsa), wind (Sanskrit: prana; Tibetan: lung), and vital essence drops (Sanskrit: bindu; Tibetan: thigle). These practices focus on straightening and unblocking the subtle channels, allowing the unrestricted flow of subtle wind. Subsequently, practitioners guide the subtle winds to enter, stabilize, and dissolve within the central energy channel. This process is explored extensively in tummo practice, which in the Six Dharmas precedes illusory body practice. Bringing the subtle winds into the central channel allows us to fully access nondual wisdom, to experience all as co-emergent bliss and emptiness, and opens the door to the experience and mastery of the extremely subtle levels of body and mind that ultimately manifest as the illusory body.

It is encouraging to recognize that when we follow the systematic course of practice and study outlined by the Buddha, we lay the foundation for its profound depth from the outset. From the earliest stages of the path, we engage with and employ the fundamental tools and techniques necessary to fully experience the wisdom inherent in the illusory body practice. One might be surprised to find that the illusory body practice includes working with and is based upon foundational topics such as the mind–body connection, impermanence and death, the eight worldly dharmas, and the elements’ dissolution at the time of death. To genuinely accomplish the practice of illusory body, it is essential to have spent significant time working with these and other areas of reflection and practice, so that by the time one encounters them in the illusory body practice, there is a depth of understanding that has moved beyond the conceptual and into lived experience and understanding. This is the key ingredient that will make one’s practice of illusory body bear its full fruit.

We find ourselves in samsara because we have mistakenly identified with a self that is separate from all that we consider as other. We have the mistaken awareness to be a self and have wrongly taken the luminous aspect of mind to be all that we perceive as other. The Buddha identified this specific “unawareness” of our true, nondual nature as the first nidana or the first of the twelve links of dependent origination. This is what sets the cycle of samsara in motion and initiates the arising of our experience of being a separate, solid, independently existent self. Attachment to this sense of self is so fundamental to our suffering that the Buddha also identified it as the second noble truth, the truth of the cause of suffering.

The nature of body and mind and their relationship are central to the Six Dharmas and illusory body practice. Body and mind each have coarse, subtle, and extremely subtle levels. When we identify with a sense of self and act out of our conditioning and habitual patterns, we confine our experience to the coarse levels of body and mind and experience them as two different entities. We identify ourselves as our solid, coarse physical body of flesh, blood, and bones, and we experience our mind as a complex web of conceptual states that inhabits this coarse physical body. We experience the body as the driver of our experience. The body manifests as it will, and our mind has no control over it. We are unable to access, let alone work with, the subtle level of body (the subtle wind, channels, and vital essence drops) and the subtle level of mind (mind beyond conceptuality) because of our fixation on our physical body as being “who we are.” We cannot access the subtle level of mind because we are subject to whatever thoughts and feelings arise in the mind. We are busy following and subscribing to every movement of the mind’s activity rather than attuning to the openness and stillness of the mind that is ever-present, whether the mind is moving or not.

This level of relationship with our body and mind corresponds with experiencing everything and everyone around us as external to us, as solid, and as somehow existing independently of causes and conditions. When this is our outlook, we are ensnared by our habitual patterns, and our mistaken perception deceives us. We know no other reality, so why would we have a second thought about it being real or unreal?

Consider for a minute, though, that there could be a greater depth, a deeper or more genuine truth right here in our ordinary experience that we are not aware of or accessing. What if our mistaken perception of a solid world of self and other could give way to a recognition that all we experience is a magical, rainbow-like, miraculous dance of awakened mind that we have the capacity to participate consciously in creating?

Part of coming to see the illusion of relative/conventional truth as a magical display rather than being deceived by our perceptions is to understand how our perception is mistaken, to untangle ourselves from our habitual ways of responding or reacting to our mistaken perception, to explore and develop the relationship between the mind and body, and to open our mind to the vast and unbounded creativity of awareness with a sense of adventure.

Accomplishing this requires an exploration of the integral connection between mind and body, beginning with the practice of calm abiding. In this practice, we join our mind with our body via the coarse breath as we experience it at the level of the subnavel chakra or energy center. While this may be a simple introductory practice, it serves as a gateway into the profound experiences of the illusory body practice. As we engage in calm abiding, we familiarize ourselves with how our state of mind and the breath impact one another. Crucially, we gain some control over the extent to which we are distracted by conceptual activity and gradually cultivate the capacity to direct our mind intentionally. This intentional placement of the mind is paramount in the primary illusory body practice. Simultaneously, we are also becoming intimately familiar with the subnavel region, which is also central to illusory body practice and understanding how the entirety of our experience manifests. We are beginning to awaken to the experience and nuances of the subtle body.

Beginning with the initial stages of the spiritual path and continuing into the first stages of the illusory body practice, we work with recognizing the impermanent, transient nature of ourselves and all phenomena. Is there anything in our experience—ourselves, our partners, our family and friends, our possessions, the earth, the universe, etc.—that does not change, develop, transform, deteriorate, and ultimately pass? Seeing this ever-changing transient nature, we reflect on it as suggested in the Diamond Sutra: “So you should view this fleeting world—A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream / A flash of lightning in a summer cloud / A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.” Perceiving the fleeting nature of our experience brings a profound appreciation for the preciousness of every moment, every connection, that allows us to access the dharma teachings and have the capacity to understand and practice them. Recognizing this evanescent nature also gives us a glimpse of how to unbind ourselves from the habitual way of experiencing our world as solid.

As our shamatha is developing and stabilizing, we begin to examine the ever-changing nature of things more closely by directing our mind to look directly at them with both analytical meditation and the nonconceptual, penetrating gaze of vipashyana. We look to see how they arise due to countless interdependent causes and conditions. We look to see if we can find anything substantial there. We begin to consider and explore the illusory, dream-like nature of phenomena, similar to how it is pointed out to us in the King of Samadhi Sutra:

Know all things to be like this:

A mirage, a cloud castle,

A dream, an apparition,

Without essence, but with qualities that can be seen.

Know all things to be like this:

As the moon in a bright sky

In some clear lake reflected,

Though to that lake the moon has never moved.

Know all things to be like this:

As an echo that derives

From music, sounds, and weeping,

Yet in that echo is no melody.

Know all things to be like this:

As a magician makes illusions

Of horses, oxen, carts, and other things,

Nothing is as it appears.

When “knowing all things to be like this” in the context of illusory body, this practice is greatly enhanced by the tummo practice that preceded it, due to its capacity to deepen the connection between body and mind on a subtle level. Having intentionally drawn the subtle wind into the central channel, our access to nondual wisdom is greatly enhanced, and this powers these illusory-body reflections.

As we begin to understand the illusory nature of phenomena, we can direct a similar gaze toward ourselves. One way to gauge the degree to which we have metabolized the understanding of ourselves as also illusory, and to further develop that understanding, is to observe how we react (or don’t) to the eight worldly dharmas. These four binary pairs of transitory experience are praise and blame, pleasure and pain, fame and obscurity, gain and loss. These experiences upon which we base hope and fear can reflect our identification with a sense of self.

A traditional way of working with these in the context of illusory-body practice is to take a pair, such as praise and blame, and to imagine two people standing on either side of you. Imagine the person on the right profusely praises you. Then, imagine that the person on your left relentlessly criticizes and blames you. Who is it that is being praised and blamed? Can you locate the sense of self? Or is it like praising and blaming your reflection in the mirror when the reflection is simply a reflection, with no inherent existence? Do either words of praise or words of blame impact the reflection? Is there any substance to the words of praise or blame themselves? Is there anything solid in those words there that could benefit or harm the essence of who you truly are? Can you locate the mind that is engaging in this exercise? Can you locate the thinker? As we engage in this practice and base the experiential understanding developed with visualizing ourselves as the yidam in the creation stage, we develop our capacity to experience body, speech, and mind as being illusory.

We expand these practices by continuously reflecting on the illusory nature of all that we encounter, asking ourselves if these appearances are solid and existent or if they are rainbow-like in nature: appearing but not existing in an independent way.

As our practice evolves and the connection of mind and body merge, the solidity of appearances becomes more translucent, more rainbow-like in nature. As our mind and body merge on increasingly subtle levels, the realization that all facets of our experience arise from our mind begins to dawn. We recognize all as the radiance of mind’s luminosity. When we genuinely realize this, we can delight and consciously participate in manifesting this magical illusory dance, marvel at its ineffable profundity, and hold with compassion how we and all beings navigating the realms of samsara suffer unnecessarily as we mistake this display as separate, solid, and independently

existent.