“Each moment is astonishing radiance, full and round, without direction or corners, discarding trifles.”

—Zen Master Hongzhi, twelfth-century China

I’ve always wondered what time is. Is it animal, vegetable, or mineral? Is it solid, liquid, or gas? What is this moment? Whoops! It’s already gone. I’m thinking about time more than ever these days because I’m eighty. This seems extraordinary. A fellow old person said to me recently, “I thought it would take longer to get old.”

Where did all those years go? Were they stolen from me, along with my ability to do handstands and my good sense of direction? Could time itself be the thief? But no, time has given me everything I’ve ever had, including my life.

Time is not a thing. You might say “I don’t have enough time,” but time is not something you possess. We speak of spending time and saving time, but time is not something you can save. You might think you can, by saving up your sick days at work, for example, or getting a faster computer. But you’re not saving time, you’re just doing something different in the time that’s given to you. The only way to talk about time is to use metaphors, so that’s what I will do.

Time is like gravity or sunshine. You can’t put it in the bank and use it later.

You could say that time is the most important thing there is because it includes everything. Can you think of anything that’s not inside of time?

Time is about as Buddhist a subject as you can find. Zen practice is all about time. We sit in zazen, bringing our attention to the present moment; we honor our ancestors of the past; and we consider karma—the law of cause and effect—which requires time, so that the cause can come first and the effect can come after.

The Buddha taught that all things are marked by three characteristics: impermanence, suffering, and no fixed self. Impermanence is time itself. Everything is constantly changing because time is constantly flowing, moving every mountain and every molecule as it goes.

Impermanence can be painful. When someone you love dies, that’s painful. But what about when someone you love is born? That’s impermanence, too. Impermanence gives us arrivals as well as departures. Winter goes, spring comes.

I want to persuade you that impermanence is beautiful, the coming and the going. Impermanence is life being lived, life living itself. That’s what you want, isn’t it? To live your life? You can’t do it unless you’re impermanent. What kind of a life would you have if you were a granite statue that never moved or changed? No blush could come to your cheeks. Michelangelo’s David never gets a hard-on.

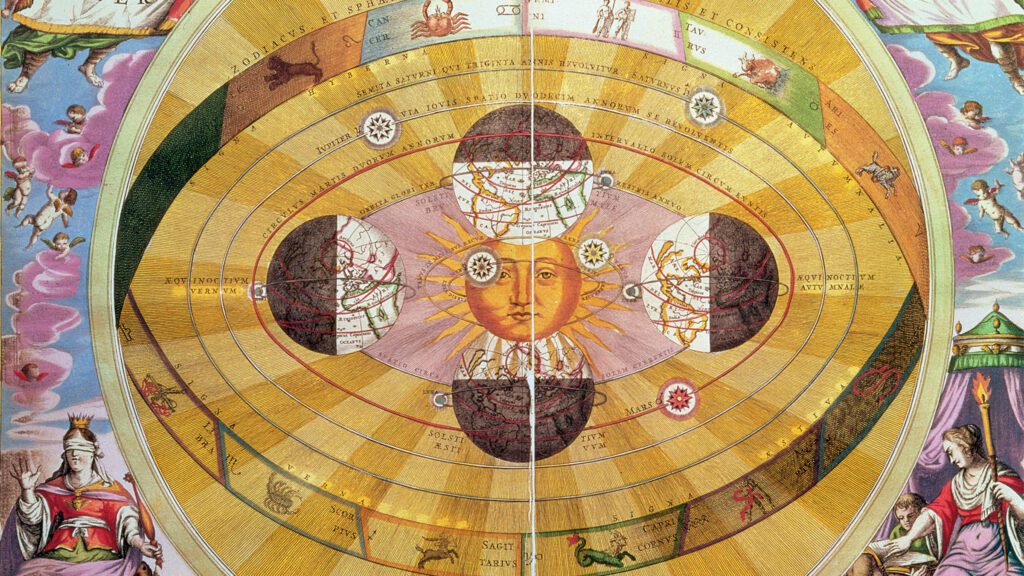

According to early Buddhist teachings, time is beginningless and endless. Buddhist teachings refer to kalpas, which are very long periods of time, and ksanas, which are very short.

Shakyamuni described a kalpa in this way: If a bird held a wisp of silk in its beak, and if, once every hundred years, it flew over a great mountain, brushing the top of the mountain with the silk, then a kalpa is how long it would take to wear down the mountain. When a kalpa ends, that’s not the end of time, because then comes another kalpa.

The Sanskrit word kalpa is sometimes translated into English as eon. The traditional meaning of eon is simply a very long period of time, and the word eon is now commonly used to mean a period of a billion years.

At the other extreme, Buddhists used the word ksana for the smallest possible amount of time that could be imagined. A ksana is imperceptibly small, just a seventy-fifth of a second. (I wonder who decided it would be that short, and how they determined that it was?) In our own time, we have the nanosecond, which is a billionth of a second, so that’s a lot smaller than a ksana, though as far as I’m concerned, the distinction between a nanosecond and a ksana is not particularly useful.

A ksana reminds us of the teaching of impermanence. Even when we think we are staying still, the ksanas are ticking by, changing us with each tick. There are said to be nine hundred arisings and ceasings within each ksana.

Scientists say that the universe began with the big bang, 13.8 billion years ago. They also say, paradoxically, that this explosion, out of which space and time were born, lasted one trillionth of a second. That’s the long and the short of it, as the saying goes.

We don’t experience these durations. These measurements may have meaning for astrophysicists and computer scientists, but they are not useful for managing our everyday lives. We don’t make lunch dates an eon in the future, and we don’t complain if someone is a few nanoseconds late. It’s the measurements in between that have meaning for human beings, and how we measure these durations has an effect on how we live.

Human beings all over the world measure this immeasurable flowing of time in seconds and minutes and hours and days and weeks and months and years. There are two kinds of measurements on this list, the ones that human beings invented and the ones that are natural, though we have mostly forgotten this distinction.

The sun gives us both days and years, and the moon gives us the tides and the lunar month. Some ancient civilizations also marked long-term alignments of other astral bodies, stars and planets, whose cycles were longer than a human lifetime and thus had to be observed and recorded from one generation to the next in order to be recognized. These measurements are all cyclical, coming around again and again. They don’t make progress along a line; they are organic circles, intertwined with the universe itself.

Homo sapiens showed up about 300,000 years ago, and the lives of those early humans were measured out in the same cycles of darkness and light that we know now. Sundials were used as early as 1500 BCE. In contrast, the hour and the week are recent human inventions.

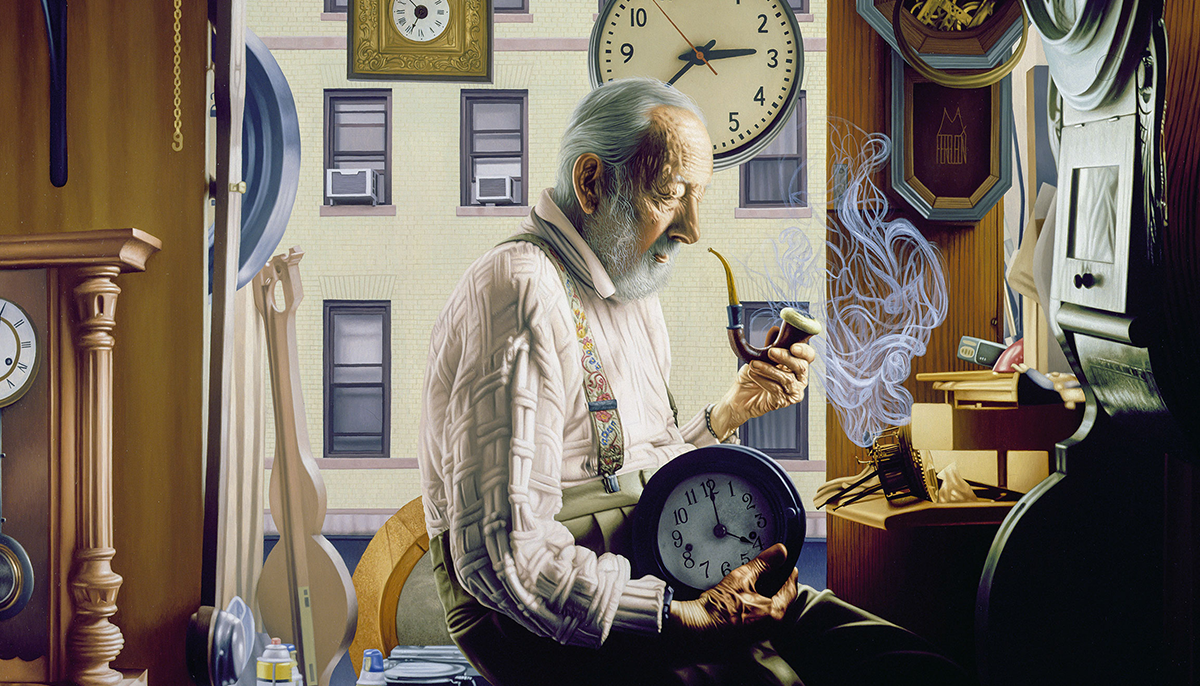

The first mechanical clocks, invented in about 1300 in Italy, were tower clocks, in town halls and churches, and the bells they housed tolled the time for the whole village. They were powered by weights, and the time measurements were based on the rhythmic swinging of a pendulum, with its repeated oscillations of identical duration, enabling the clock to measure twenty-four equal hours. The tower clocks didn’t yet have a face or hands, but they were built tall (they were often the tallest building in the village), the better to send their ringing far and wide.

I was interested to learn that the time it takes a pendulum to complete an arc depends only on its length. A five-pound rock tied to the end of a yard-long rope will swing back and forth in the same amount of time as a one-pound rock. Furthermore, and even more surprisingly to me, once you set a pendulum to swinging, it will take just as long to complete the wide arc at the beginning, as later, when the arc decreases. The time it takes to swing back and forth depends entirely on the length of the cord or the chain. It was Galileo who discovered this law of the pendulum. I never noticed this in the many times I pushed a child on a swing. No matter how high she goes, even if it’s frighteningly high, almost horizontal, it takes her just as long to swing back and forth as when she lets the swing die down to a gentle arc, and this is true no matter how much she weighs, whether she’s two or six, or how hard I’ve pushed her. Another mystery of time.

When mechanical clocks were first invented, ordinary people didn’t immediately organize their lives by the hours on the clock. It was enough to say, “I’ll see you at the bridge when the sun is high,” or “Meet me at the tavern at sunset.”

The first people to regulate their days according to the clock were probably monastics—Benedictines in Europe and Zen monks in Asia, who established their monastery schedules according to the hours of the day. They had a different attitude toward the hour than we do. Time belonged to God, or to the dharma, and the measurement and marking of time was the monastery’s job. No individual would have had a timepiece. The monks just followed the time signals, which were sacred sounds in themselves. In a Benedictine monastery, the bells in the tower give the signal to go to the various “offices” of the day, the singing of psalms, chanting of prayers, from matins to vespers.

The same is true in a Zen monastery. Time in the monastery belongs to everybody together, and the marking of time is itself part of the spiritual practice. It’s a kind of dance, with instruments of variously textured resonances: the wooden mallet and block of the han, the Japanese fish drum called the mokugyo, the big taiko drum, the big and little bowl-shaped bells, the wooden clappers, the iron gong of the umpan—they give the signals for meditation, or work, or meals. This is the music of time passing. How different from the hall buzzer in high school, which, without any artistry or touch of human hand, tells you to rush to the next class.

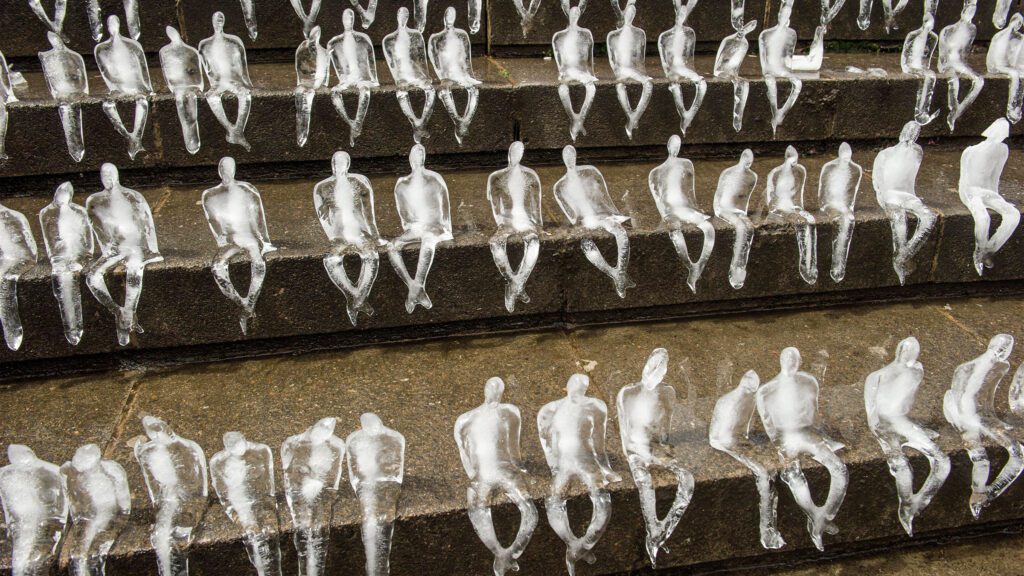

One of the remarkable things about practicing in a traditional monastic setting like Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, where I have practiced, is the opportunity to explore time in a deep way. Zen is the practice of being present right now, in this very moment. In zazen, you keep bringing yourself back to this body, this breath, this unmarked now, back to the uncalibrated gurgling of the stream, the sound of time’s flowing. So it seems contradictory that the most basic instruction of the practice period is: Follow the schedule! Go wherever you’re supposed to go whenever you’re supposed to go there, and don’t be late! In fact, punctuality is so highly valued that if you’re not five minutes early, you’re late. On the face of it, this seems like the opposite of entering deep time and being present right where you are.

But there’s liberation in the schedule because it’s the schedule for everyone. When I was a monk at Tassajara for three months of intensive practice, I was freed from meeting deadlines or keeping track of my time in the usual way. The bells and signals did that for me. “My time” didn’t really exist. I didn’t have to prioritize tasks or be responsible for finishing a piece of work as an individual. During afternoon work period in the kitchen, as four of us sliced beets together in silence, we kept on going until the three-gallon bucket we were asked to fill was full, and then we went on to the next task, and if we were in the middle of something when the bell rang to end work period, we stopped anyway.

I didn’t need a watch. The bells and drums were like the caller in a square dance; you just do the next thing when it’s time to do it, you do-si-do, you duck for the oyster, and dive for the clam, and you throw your whole self into it, along with everyone else, becoming one organism. When we fifty black-robed bipeds formed a long line and walked up the hill in outdoor kinhin (walking meditation), then made a U-turn to curl back down, we became a single centipede.

The schedule strengthens the feeling of sangha, of belonging to a community. Without our bells, we might wander about in different directions, nap at different times, practice without any shared ritual.

The industrial revolution in the eighteenth century drastically changed our view of clock time. In Europe, the hours of the day no longer belonged to God but to the boss. Time became money. Before that, a cobbler was paid for a pair of shoes he made on his own time. Farmers’ livelihood depended on their crops and animals, which depended on working with the rhythm of the seasons and the weather, not on counting hours. But factory work was different. Owners were buying the workers’ time, measured on the clock.

The classic Charlie Chaplain movie Modern Times is a horrifyingly funny representation of time as a commodity. Charlie Chaplain is working on an assembly line, tightening bolts, and the boss, who owns Charlie’s time, is sitting in an armchair in his office. He gives the signal to speed up the movement of the belt, and as it goes by faster and faster, Charlie can’t keep up with it, and he gets caught by the belt and goes down the chute with the bolts into the innards of a great machine, himself becoming a cog. This is what happens when one person’s ineffable, immeasurable, radiant time is measured and chopped up into chunks that can be owned by another person.

Almost all work is now paid for by the hour, though the amount people get paid per hour varies. Even people on salaries are usually paid on the basis of a certain number of hours of work per week. This system puts a big stress on the precious hours of the day, hours that are actually precious not because they are worth dollars but because they are full of astonishing radiance. Believing that time is money makes it hard to lie in a hammock doing what looks like nothing when you could be accomplishing something. We are bewitched into thinking that time is all for doing, not for being. As our dear Buddhist elder the late Wes Nisker said, “Let us remember that we are called human beings, not human doings.”

In her excellent recent book Saving Time, writer Jenny O’Dell makes the important and startling connection between the commodification of time in our everyday lives and the commodification of the life and resources of the planet. Just as time is not money, planet Earth is not a stockpile of resources for human use. But our social systems and our economies don’t see the geological life of Earth as having subjectivity. We don’t hear rocks preaching the dharma, as Dogen would have it. Instead we see resources to be extracted. This is a huge subject, which Odell explores at length in her book.

We’ve lived with the hour for only 0.04 percent of our species’ time on Earth, but by now the hour—and the week, too—seem as inevitably true as the day and the year. However, you could get off the grid and live a life without a single “Wednesday” in it, or a single “ten o’clock in the morning,” but you could not live a life on planet Earth without days, without those regular cycles of darkness and light.

I got away from clock time when I went on a monthlong retreat at a cabin in the woods, without any timepiece. I ate when hungry, went to bed when sleepy, and got up when I woke up. I meditated first thing in the morning and again at dusk, for as long as it took an incense stick to burn down. For a whole month I stepped aside from responsibilities, and I had no deadlines. I couldn’t be late, because whatever I did, I was doing it right on time.

I wrote in the mornings, and when the sun was high and I was peckish, I had some lunch. In the time that came after noon, I went for a walk and did fix-it projects around the cabin. I was in touch with my body’s rhythms, I noticed which windows the shafts of sunlight entered at midday, I noticed what phase of the moon it was and whether it was bright enough to take a walk at night. I heard the katydids singing at dusk. I was in that particular place, in that particular moment. It was liberating.

I wouldn’t have wanted to stay there forever because I would have gotten lonely. I need to know what o’clock it is, as they used to say, in order to connect with other people, in a society where we are all bound together by the clock. The hour that we invented both serves us and holds us hostage.

You might try spending a whole day without consulting a timepiece. From the time you get up in the morning until the time you go to bed at night, avoid your devices. It’s hard to do. Time is blinking at you from every direction: from the dashboard of your car, from your electric stove. You could put masking tape over them the night before and put your phone away. Not knowing what “time” it is can help you to notice your body’s rhythms. It can help you to be present when you are eating, walking, bathing…. See how a day feels, how long a day lasts. The Jewish practice of the Sabbath is like this, with the additional (and beautiful) aspect that it’s a practice taken up in the family, in community.

We have always had the day. What we call a “day” existed millennia before human beings came along and put a word to it. I want to sing the praises of that circle, the round day, made of both darkness and light. Isn’t it wonderful that this essential unit, the day, is shared not only by all human beings but by all the other beings who ever lived on this planet? All of our lives have been made of the same wheeling. How fortuitous that our planet is turning on its axis, around and around, again and again, like a heartbeat.

Thank you, Earth, for turning as you do—our lives depend on it. It could have been otherwise. The moon, because it always shows us the same face, rotates only once a month, as it makes a full circle around the earth. By contrast, Venus, our nearest neighbor, takes about six thousand hours (about eight months), to turn all the way around on its axis. Sometimes I wish there were more hours in a day on Earth, but not that many! How lucky we are to get a fresh day each morning when we wake up—a day with just the right amount of time in it for two or three meals, and some work and play. Thank you, day!

The time of our lives was born with the big bang, and all the days of our lives have been given to us by the universe.

Universe, what can I give you today?

Each moment is astonishing radiance, full and round, without direction or corners, discarding trifles.