And which are the three factors of the donor? There is the case where the donor, before giving, is glad; while giving, his/her mind is bright and clear; and after giving is gratified. These are the three factors of the donor.

—the Dana Sutta, translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

I remember barren trees, the gray winter sky pressing down like a sheet of dull metal, and a snowy parking lot next to low rectangles of brick buildings. This was the hospital in Ohio where my mother almost died from a burst appendix when she was seven months pregnant. I was only eight or so. My father would drive my younger brother, sister, and me to the hospital, parking the car where we could see the window of our mother’s room, and he would leave us. Children weren’t allowed inside the hospital.

This did not seem unusual. We wore hats and coats and mittens. We were okay. After a few minutes, our mother would wave to us from her window, and awhile later our father would return and drive us home. He’d have a handful of a few different kinds of Smucker’s jams in small, white plastic cups that our mother saved for us from her hospital breakfast tray. They felt like jeweled talismans from the world we weren’t allowed to enter, proof of our mother’s love.

My parents didn’t talk very much about this time. They must have told us that the mysterious and tiny baby, named Mary Beth by our mother, was not ours to keep. After we had repeated the parking lot routine for weeks, our mother came home to the trailer in which we lived, and her older sister, Aunt Mildred, flew in from Hawaii. When our aunt returned to Hawaii, she took the baby with her.

All of this made sense to my eight-year-old self because there were, after all, three of us children sleeping in the narrow back room of the trailer and two adults in the front bedroom. There wasn’t really room for another child. Our aunty and uncle had no children of their own, and they lived in a house.

It was only very late in his life, shortly before he died, that my father spoke to me about his memory of that time. I was his first child, and part of my role was that of confidante.

“Leaving you kids in the car, I’d go inside the hospital to visit Mom, then I’d look at Mary Beth in the incubator,” my father said. “She was so little, with long arms and legs like a spider. Her wrist was the width of a pencil. I’d look at her, but I never touched her. I knew if I did, I’d want to keep her.”

What do we keep, and what do we give away? My aunt, my little sister’s adoptive mother, decided to keep the name my mother had chosen for her.

“She was born near Christmas, so I named her Mary for Jesus’s mother and Beth for Bethlehem,” my mother once explained.

“Mom, none of us is Christian,” I said.

She laughed.

My parents’ generous gift of a child who grew up thousands of miles away on a tropical island never felt strange or strained. My aunt regularly sent us baby photos, then little kid photos, then bigger kid photos of her daughter, and while she definitely looked like us, her life was separate from ours. Hers was a different culture, a different way of speaking, a different climate.

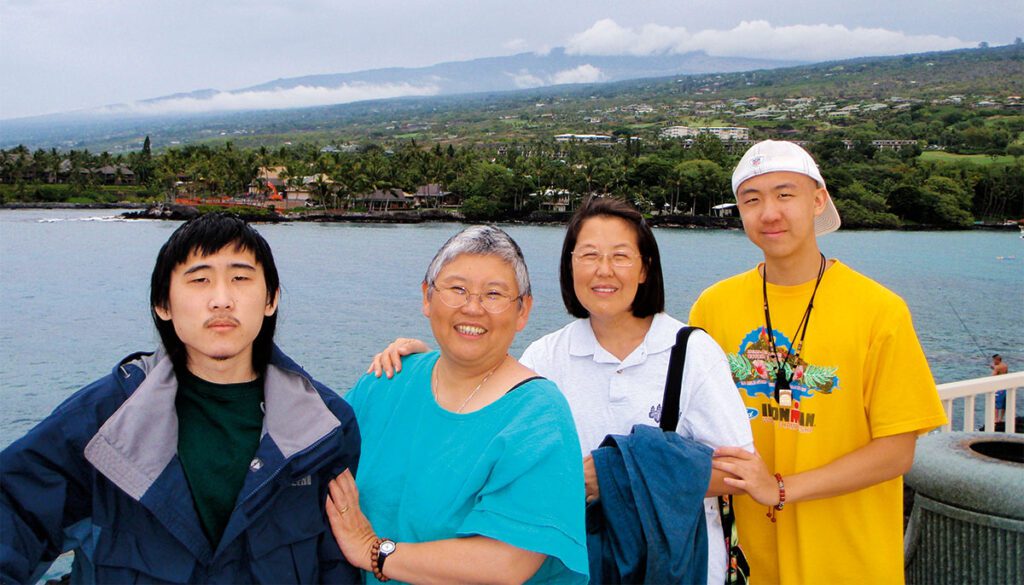

My sister-cousin, Rev. Mary Beth Jiko Nakade, grew up to be a Soto Zen priest. She and I occasionally joke that when we give dharma talks on dana, the foundational Buddhist practice of generous and selfless giving, we think about how our parents set an extremely high bar.

Both of us raised our own children in very similar ways, breastfeeding and sleeping with them until they were ready to leave the family bed. As adults and Buddhist teachers, we have forged a bond of mutual admiration as well as the affinity of Zen meditation and practice, and our children know they are first cousins. My cousin, who is my youngest sister, is in her kindness and good-humored patience a dharma role model for me.

And which are the three factors of the recipients? There is the case where the recipients are free of passion or are practicing for the subduing of passion; free of aversion or practicing for the subduing of aversion; and free of delusion or practicing for the subduing of delusion. These are the three factors of the recipients.

—the Dana Sutta

In Buddhist countries in Asia, laypeople learn never to go to the temple empty-handed. However, things are different here. I teach at East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland. Because we’re centered in diversity, inclusion, and social justice practices, we operate on a gift economics, with no set fees. We’ve gotten comfortable with “giving the dana talk” and asking people to give generously. However, very few of our teachers can live solely on dana. In a capitalist culture, where people are conditioned to shop for products on sale at the lowest price, or no price, this has often felt like swimming upstream, occasionally leaping dams. Many of the communities we serve are low-income ones.

“I sometimes fantasize about saying, ‘Hey, if you find yourself wondering how much to give, consider this: my parents gave their fourth baby to my aunt and uncle in Hawaii,’” I’ve joked to Mary Beth. “But of course, I’d never actually say it.”

I’m nearing seventy now, and I wonder how they did it. My parents, who died in the nineties, were Japanese Americans who in some ways seemed so unremarkable. Yet they were capable of a generosity that was perfect and quiet and completely inconceivable to me. Although I’m a parent, and my son and I have lived together in Oakland for so many years, through a pandemic and anti-Asian violence, as well as thousands of the daily interactions that together mean “you are the one I love,” my own parents’ stories remain unknown to me.

What did my mother think and feel in the hospital when she carefully stacked the little plastic cups of grape and strawberry jam? What was in my father’s heart when he marveled at the baby in the incubator, his hands by his sides?

It’s not easy to take the measure of the merit of a donation thus endowed with six factors as “just this much a bonanza of merit, a bonanza of what is skillful—a nutriment of bliss, heavenly, resulting in bliss, leading to heaven—that leads to what is desirable, pleasing, charming, beneficial, pleasant.” It is simply reckoned as a great mass of merit, incalculable, immeasurable.

—the Dana Sutta