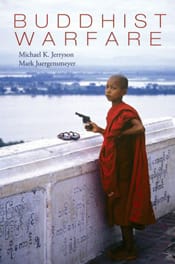

Buddhist Warfare

Edited by Michael Jerryson and Mark Juergensmeyer

Oxford University Press, 2010

$29.95; 257 pages (paperback)

Although all major world religions claim to advocate peace, they have had a mixed record of living up to their professed values. The biblical religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—are widely seen as being embroiled in the violence that periodically flares in the Middle East. Hinduism and Sikhism’s reputations as peaceful religions are likewise impaired by outbreaks of violence between their communities in India.

Buddhism also has a reputation of being a nonviolent religion, but history tells a different story, as the current conflicts in Sri Lanka and Thailand attest. Anyone who is interested in learning more about Buddhism’s ambiguous relationship with violence would be well advised to read the newly published anthology Buddhist Warfare, edited by Michael Jerryson and Mark Juergensmeyer. As Jerryson indicates in his introduction, one of the chief goals of this volume is to challenge “the social imaginary that holds Buddhist traditions to be exclusively pacifistic and exotic.” The authors make it clear that Buddhist traditions, like all other religious traditions, are human institutions, and thus are not immune from the problems that afflict human communities around the world.

Chronologically, the volume spans more than two thousand years, beginning with an overview of Buddhist involvement in warfare and violence during the first millennium, drawn largely from East Asian sources. This is followed by an exploration of a Mahayana sutra that sanctions warfare under certain conditions. The collection then jumps to the early modern period, with essays on legally sanctioned violence and warfare in Mongolia and Tibet during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These are followed by essays on the “patriotic” support given by Buddhists to war efforts during the twentieth century—in Japan during the wars of the first half of the twentieth century, and in China during the Korean War. The final two essays look at the contemporary conflicts involving Buddhist communities in Sri Lanka and Thailand.

The focus on more modern examples will make the book of interest to a broad range of readers. The volume also makes a great contribution to anglophone students of Buddhism by publishing an English translation of Paul Demiéville’s groundbreaking 1957 essay, “Le bouddhisme et la guerre.” When Demiéville’s piece was first published it was preceded by an essay on the Japanese warrior monk (sōhei) tradition, and it sought to demonstrate that this was not an aberrant cultural phenomenon. It is a fascinating work, exploring a number of paradoxes with respect to Buddhism and violence. One only wishes that the editors had also included the essay on the warrior monks with which it was originally paired.

Mahayana Buddhist ethicists, Demiéville explained, made a number of exceptions permitting violence under certain circumstances. While Buddhism may have played a role in the demilitarization of certain Buddhist communities, Demiéville pointed out that it did not have this effect everywhere. The essay details a number of examples of Buddhist involvement in violent conflicts, drawing primarily on premodern Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Tibetan historical sources.

Next is Stephen Jenkins’ essay on the Satyakaparivarta, a Mahayana scripture composed sometime during the first half of the first millennium. This scripture appears to be addressed to kings, and provides them with religious sanction for engaging in warfare and torturing and executing prisoners. The essay provides abundant background information, but unfortunately Jenkins does not provide a clear introduction to the scripture that is the ostensible focus of the essay, and includes only one short quotation from it.

This is followed by a short but fascinating article by Derek Maher that explores the Fifth Dalai Lama’s attempt to justify the violence against rival religious groups inflicted by his Mongol allies in 1642. The essay is nicely complemented by Vesna Wallace’s contribution, which focuses on the legal system adopted by the Mongols following the conversion of the Ordos and Tümed Mongols to the Geluk tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in the late sixteenth century. The essay covers the outlawing of traditional Mongolian shamanism and the attempts to legitimate the practices of torture and capital punishment that persisted well into the modern period.

The remaining four chapters focus on the modern era. Brian Victoria’s essay, “A Buddhological Critique of ‘Soldier-Zen’ in Wartime Japan,” is the latest contribution in his oeuvre, which has focused on the militant roles of some Zen priests in Japan during the wars of the twentieth century. In this essay, Victoria explores the concept of “soldier Zen” (gunjin zen) advocated by several prominent Zen masters, and introduces the history and key figures of this period. Though he covered this in more depth in his 1997 book Zen at War, here he advances the somewhat radical thesis that “by virtue of its fervent if not fanatical support of Japanese militarism, the Zen school, both Rinzai and Soto, so grievously violated Buddhism’s fundamental tenets that the school was no longer an authentic expression of buddhadharma.”

Although extremely thought provoking, this essay has several problems. First, his blanket condemnation of the Japanese Zen tradition fails to acknowledge the complexity of the situation in wartime Japan. It is by no means the case that Zen Buddhists universally supported the war effort; some resisted it, as Victoria himself has documented in his earlier writings. Moreover, Victoria engages in what we might term “constructive Buddhist theology,” in that he takes a very strong and controversial position regarding “Buddhism’s fundamental tenets.” He rejects, for example, the Buddhist scriptures that permit bodhisattvas to engage in violence provided that their underlying motivation is compassionate.

Victoria is of course entitled to this opinion, one that is likely shared by other contemporary Buddhists. However, his definition of “Buddhism’s fundamental tenets” is so restrictive that it seems unlikely that many (perhaps any?) Buddhist traditions would meet his high standard for an “authentic expression of buddhadharma.”

While Victoria’s article revisits a facet of Buddhism that is now well known, largely due to his own efforts, Xue Yu brings to light a chapter in Chinese Buddhist history that is poorly understood in the West. This is the history of Buddhism in China during the early Communist era, from 1949 to 1953. He demonstrates how many Buddhists, no doubt aware of the challenge that the Communist state posed to their religion, went out of their way to demonstrate their nationalism. This included patriotic support of the Korean War effort that used the very same flexible interpretation of Buddhist ethical teachings that Victoria condemns in his essay.

The volume then turns to two contemporary Buddhist conflicts, one in Sri Lanka and the other in Thailand. Daniel Kent’s essay, “Onward Buddhist Soldiers,” goes beyond the usual approach of works on Buddhism and violence, which is to explore justifications for violence provided by Buddhist scriptures or Buddhist leaders. Kent instead focuses on how Buddhist monks minister to soldiers in the Sri Lankan army. He contends that they attempt to tread the fine line between encouraging and discouraging the soldiers to kill. They focus on intentionality, urging the soldiers to act with wholesome intentions. Any violence, they explain, should be motivated not by unwholesome passions such as hatred, but rather by relatively positive intentions, such as the desire to protect the innocent.

Jerryson’s contribution focuses on the most recent development, the outbreak of violence over the last decade in southern Thailand. This is a region with a large Malay Muslim population in what is otherwise an overwhelmingly Buddhist country. The essay focuses on the commissioning of “military monks” (thahānphra) to protect Buddhist temples and monasteries, and explores the consequences of this. These include the transformation Buddhist spaces into military spaces, with a corresponding loss of a sense of sacredness. He also demonstrates that this is not a modern development, but is linked to an older alliance between Buddhist monastic institutions and the military in Thailand. This alliance blurred the roles of monk and soldier, with the latter often taking on temporary monastic ordination.

The volume concludes with a reflection by Bernard Faure, who addresses a number of themes that run through the book. He suggests that the justifications for violence throughout Buddhist history sound like casuistry, much like the arguments invoked in the present day to justify warfare or torture. He cogently argues that since Buddhists emphasize compassion as one of their key teachings, Buddhists in particular need to clearly elucidate their often-complex views regarding violence. He concludes by suggesting that we “ask ourselves whether being a Buddhist does not require a confrontation with the violence that lurks at the heart of reality (and of each individual), rather than eluding the question by taking the high metaphysical or moral ground.”

Faure’s question is an excellent one. As any meditator knows, the capacity of the human mind for distraction, diversion, and denial is vast. Moreover, it is arguably the case that the basic human tendency to idealize our “insider” group, and demonize an “other,” “outsider” group, lies at the root of human conflict. I would also suggest that the tendency of some Buddhists (myself included) not to acknowledge the pitfalls encountered by Buddhist communities in past and present times, is a symptom of the underlying disorder that results in outbreaks of religiously inspired violence. A close reading of this book will be an eye-opening experience for readers who hold any idealistic views of Buddhism and its history.