“My religion is very simple. My religion is kindness.” —His Holiness the Dalai Lama

“It’s in the teachings of my own Tibetan Buddhist tradition where I find many of the tools that help me navigate the challenges of everyday living in the contemporary world,” says scholar and translator Thupten Jinpa.

Ironically, the Buddhist tradition he finds so helpful in the modern world was developed during hundreds of years of self-imposed isolation inside Tibet, scrupulously avoiding contact with outside influences. That changed dramatically in 1958, when a failed revolt against Chinese occupiers drove hundreds of thousands of Tibetans, including major Buddhist figures such as the Dalai Lama, into exile.

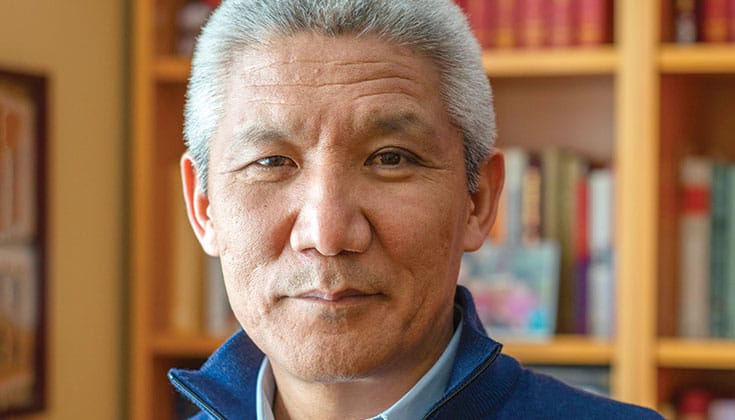

Thupten Jinpa Langri was one of that first generation of Tibetans who grew up in exile. Now fifty-eight, he has been a pioneer in helping the Tibetan Buddhist tradition find its place in the world. The bridge he’s found between modern society and his ancient religious tradition is compassion.

Even in the contested political arena, compassion is one value that both sides of the spectrum are eager to claim.

“Compassion turns out to be the common ground where the ethical teachings of all major traditions, religious and humanistic, come together,” says Jinpa, who is the author of A Fearless Heart: How the Courage to Be Compassionate Can Change Our Lives. “Even in the contested political arena, compassion is one value that both sides of the spectrum are eager to claim.”

Jinpa defines compassion as “a sense of concern that arises when we are confronted with another’s suffering and feel motivated to see that suffering relieved. Compassion is a response to the inevitable reality of our human condition—our experiences of pain and sorrow—and offers the possibility of responding with understanding, patience, and kindness.”

It’s no coincidence that his words echo those of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, since he is best-known as His Holiness’ principal English translator since 1985. This former monk is now a family man living in a modest townhouse in Montreal. I sipped coffee with him on his backyard patio as he talked about how compassion permeates his personal life and his work as a scholar, author, translator, and leader in the dialogue between Buddhism and science.

Thupten Jinpa was just one year old when his family fled to India in 1959 in the wake of the Dalai Lama’s escape. At a school for refugee children, he had a traditional Tibetan Buddhist education. “Every Sunday afternoon, a monastic teacher would give a dharma teaching,” Jinpa remembers. “He told stories about Buddhism coming to Tibet, the sacrifices great translators made, and the invention of the Tibetan language system. The traditional culture was being preserved with the children.”

When he was six years old, Jinpa was chosen to walk alongside the Dalai Lama when His Holiness visited the school. “I remember holding his hand and trying to keep up with his pace,” he says. Jinpa asked His Holiness if he could become a monk, to which His Holiness replied, “Study well and you can become a monk anytime you wish.”

When Jinpa was nine, his mother passed away and his father became a monk, which was not uncommon upon the death of a spouse. Two years later, Jinpa decided he wanted to become a monk too. He joined his father’s monastery in southern India, but soon became frustrated with its lack of academic exploration. “The main education consisted of memorizing and chanting liturgical texts without knowing their meaning,” he says. “I felt intellectually restless and increasingly uncomfortable.”

Jinpa realized that learning English was the key to exploring new ideas. “I had a basic ability to read English but my conversational skills were almost nonexistent,” he says. “I made do with comic books and a cheap used transistor radio. The Voice of America had a unique program broadcasting in English, in which the presenter spoke slowly and repeated every sentence twice. This was immensely helpful.”

The early 1970s were the height of the hippie movement in India. Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama’s home and seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, was a favorite spot to hang out, smoke some chillums, and explore Buddhism. His Holiness’ teachings attracted spiritual seekers from across the globe, with whom Jinpa would practice his English, read Western literature, try exotic new foods like pancakes, and learn to use a knife and fork.

“Through English, I learned to read a globe,” Jinpa says. “That made the news of great countries come to life—England, America, Russia, and our beloved Tibet, which had tragically fallen to Communist China.”

At the same time, Jinpa deepened his knowledge of Buddhism and the Tibetan language with a teacher named Zemey Rinpoche, who recognized the young monk’s restless intellect. In 1978, Jinpa moved to Ganden, a large monastery in southern India renowned for its intellectual rigor. On completing his studies there, he was awarded the degree of Geshé Lharampa, the highest level of academic achievement in Tibetan Buddhism.

Then in 1985, twenty years after he had held the Dalai Lama’s hand as a small boy, Thupten Jinpa got a surprise call. His Holiness was scheduled to teach in Dharamasala but his English translator was not going to arrive in time. Jinpa had been recommended.

At first, he tried to refuse. “I said, ‘No, no. I’ve never done this before,’” he remembers. Though nervous, Jinpa eventually agreed to do it. The audience responded well to his style of translation, and when the official translator arrived, the audience requested that Jinpa continue.

In my wildest dreams, I never thought I would have the honor of serving the Dalai Lama so closely.

Afterward, the Dalai Lama asked to see Jinpa in his office, where he said, “I know you. You’re a good debater. You’re a good scholar. But I never knew you spoke English. How come I never knew?” Jinpa sheepishly explained to His Holiness that he’d kept a low profile because if others in the monastery knew how well he spoke English, he’d be inundated with tasks. His Holiness said, “People tell me that you have a very easy English to listen to. Would you come with me when I need you to interpret, and on my travels?”

Jinpa was in tears. “In my wildest dreams, I never thought I would have the honor of serving the Dalai Lama so closely,” he says. “For a Tibetan who grew up as a refugee in India, serving the Dalai Lama was also a way to honor the sacrifices our parents had to make in their early years of exile.”

Jinpa began translating for the Dalai Lama in India, and two years later traveled to the West for the first time. “The first country we stopped in was West Germany. I had never seen a supermarket or motorways with two lanes. The colors were very muted, even the houses and clothes. There were very few people, whereas in India there are people everywhere. It felt too neat and too clean. On the same trip, we went to the United States. Even the air smelled different.”

“My relationship with Sophie involved a bit of a learning curve,” says Thupten Jinpa about life as a married man. “It’s funny how the things that become so important in your life tend to happen accidentally.”

Though he was now the Dalai Lama’s principal English translator, Jinpa continued to develop a life independent of this role. He went to Cambridge University to pursue a B.A. in Western philosophy, and eventually got his PhD in religious studies.

Away for the first time, he began to think that his future might not be in the monastery, because remaining a monk meant he would eventually become a teacher. “Right from the beginning, I recognized that in serving His Holiness, I was also serving the world,” says Jinpa. “Whereas, if I tried to be a teacher in my own right, I may be successful, but my reach would always be limited.” He began to see he was in a unique position: “The strange karma I had of being a monk, yet knowing English, was pushing me to be a medium between the two cultures.”

I’d had a yearning for family since my early twenties. The yearning was even stronger after my undergraduate time at Cambridge. So I made the decision to give back my vows.

Jinpa also had to face what his heart was telling him—he wanted a family of his own. “I’d had a yearning for family since my early twenties. The yearning was even stronger after my undergraduate time at Cambridge. So I made the decision to give back my vows.”

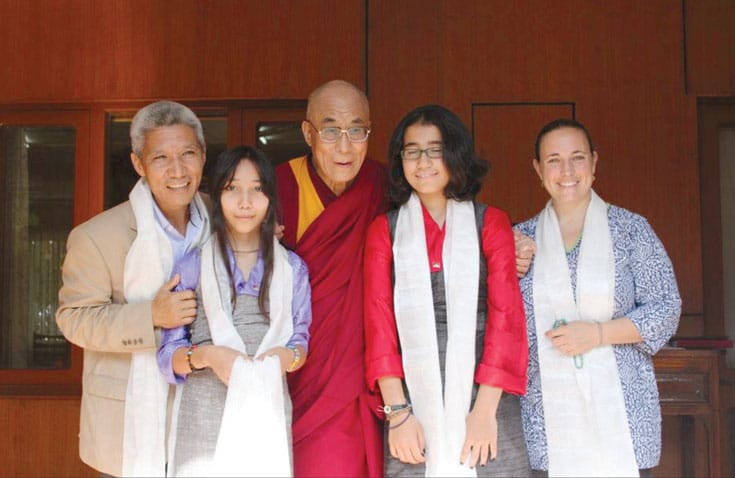

Jinpa wrote the Dalai Lama a long letter to apologize if he had disappointed him. A couple of months later, Jinpa got a call that His Holiness wanted him to translate in Switzerland. He explained that he was no longer a monk, but the Dalai Lama’s secretary said that His Holiness had personally requested him.

When he saw His Holiness, Jinpa remembers, “I said, ‘I’m so sorry to turn up like this in trousers instead of robes.’ The Dalai Lama laughed and said, ‘You always had a big head. But now, with hair, it looks even more impressive.’ His Holiness told me, ‘I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t disappointed and saddened by your leaving the monastic life, but I know you have not taken this decision lightly. I respect your judgement.’”

Then the Dalai Lama gave Jinpa this advice: “I have no experience in family life. But I have seen enough broken relationships to know that you shouldn’t have children before you’ve found the right partner. There are so many broken families with small children caught in the middle and parents expending so much energy trying to resolve conflicts.”

Jinpa says His Holiness’ reaction to his decision taught him a lot about compassion. “He could have scolded me. But he got to my level, understood me, and looked at the situation from my perspective. That changed everything.”

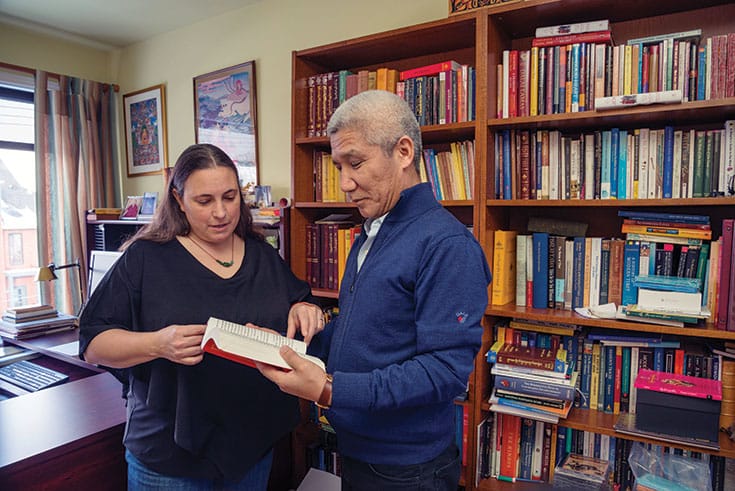

A year later, when His Holiness couldn’t make a scheduled radio interview in Montreal, he sent Jinpa in his place. Because Jinpa did not speak French, Sophie Boyer, a volunteer for the Canada Tibet Committee, went to the studio to help.

“The first time we spoke was on the radio,” he says. “Later she told me she was planning to go to India to learn Tibetan.” Jinpa arranged for Sophie to stay in his former monastery and he went back to Cambridge, where he was working as a research fellow in Eastern religion. The two stayed in touch and eventually married. Thupten Jinpa now smiles as he remembers the learning curve that being in a romantic relationship entailed.

“In the Tibetan community, once you grow up, there’s not much physical contact,” says Jinpa. “And having been a monk, physical intimacy was not part of my life, nor was the sharing of emotions. My wife, she’s French-Canadian, which is a culture that expects that intimacy. So learning that took a little while.”

Jinpa and Sophie have two daughters, now both at university, and Jinpa says becoming a father changed his perspective on compassion, which had been a little theoretical. “It helped me make real many of the sentiments around compassion that we, as monks, visualize and imagine. In the face of an infant’s immediate need, a loving parent is completely there for that child. That unconditionality, that total presence, is the quality of mind and heart that compassion and meditation tries to cultivate for all beings.”

Jinpa’s youngest daughter, Tara, taught him many lessons. “Between ages two and four, she was completely unmanageable sometimes,” he says. “I remember getting caught being very angry and frustrated. In relationships you have with colleagues or teachers, you’re not completely exposed from the personal side, whereas in the context of family life, you are as bare as you can be.”

Being a family man has allowed Jinpa to act as a bridge between the Dalai Lama and lay audiences. “Sometimes a question does not fully capture what an audience member wants to ask,” says Jinpa. “As a lay person with a family, I may be able to translate those unwritten assumptions. Conversely, I may also be able to explain certain points of His Holiness’ to the audience in a way that is more understandable because of my life situation.”

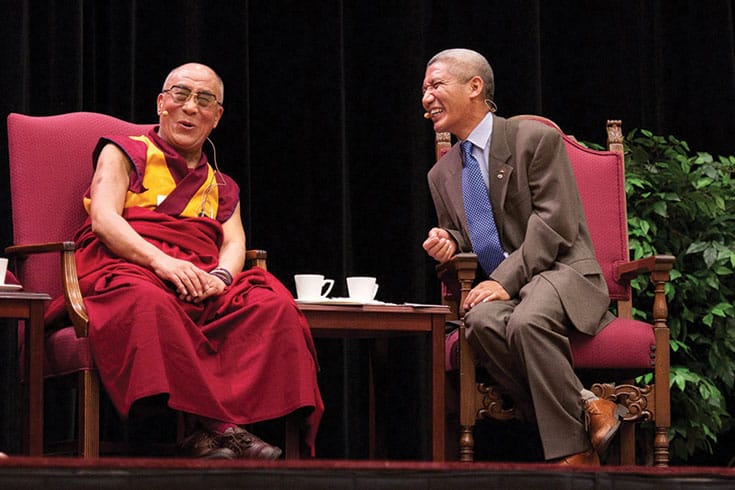

“I’ve always been interested in ideas, but I was never that interested in science,” Thupten Jinpa acknowledges. That changed in 1987, when he translated for the Dalai Lama at the first Mind and Life conference. For the first time, contemplative practitioners and leading scientists came together for a dialogue about how the inner research of meditation and the outer research of science could work together.

“For His Holiness,” says Jinpa, “what science offers is a very empirical way of grounding many aspects of Buddhism—the importance of self-discipline, having mastery of your emotions, having awareness of your own eternal mind. If you’re able to explain these ideas in scientific language and cite scientific findings, it’s a much more accessible way of conveying them to Western minds.”

There was more skepticism on the scientific side. “When the first Mind and Life Dialogues began, compassion wasn’t a major field in science,” says Jinpa. “But more and more research indicated evidence of empathy in animals, so you could no longer say altruism has been put upon us by culture. Until then, that was what a lot of scientists took morality and religion to be—a human invention to keep a lid on this brute nature. Otherwise, we’d be at each other’s throats.”

Jinpa’s role was more than translating mere words. “At the time, the conceptual framework wasn’t there for scientists to understand Buddhist philosophy,” Jinpa says. “If you started using Buddhist jargon, they had no way of appreciating the insights.” To build a foundation for productive dialogue, Jinpa and His Holiness had to create connections beyond the technical language of both worlds.

His Holiness’ message about the importance of compassion began to attract greater interest in the scientific world. Jinpa says that the Mind and Life conference at MIT in 2003 was a milestone. “That represented, from a mainstream scientific community’s point of view, a begrudging acceptance of the role Buddhism has had in shaping science.”

It’s my belief that the preservation and dissemination of classical Buddhist knowledge and its practices, including compassion, is good for the world.

Compassion and the benefits of meditation practice are now considered legitimate subjects of scientific study. In 2005, His Holiness was a keynote speaker at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Since its first dialogue in 1987, the Mind and Life Institute has held more than thirty events on a wide range of subjects, including ethics, neuroplasticity, altruism, economics, and more. Thupten Jinpa is the chair of its board.

Another organization studying and promoting compassion is the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE) at Stanford University, which Jinpa helped found with neurosurgeon James Doty. There Jinpa developed the Compassion Cultivation Training program (CCT), combining mindfulness practice, compassion meditation techniques, and Western psychological insights. Free of religious terminology and with testable results, this eight-week training in empathy and compassion has been taught to thousands of people from Stanford students to Google engineers. Many of its principles and practices are found in Jinpa’s book, A Fearless Heart.

Thupten Jinpa says that over time he came to recognize that his destiny is to integrate classical Tibetan Buddhism into the contemporary world. He therefore turned his attention to preserving the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, in particular the extensive philosophical teachings that the Dalai Lama refers to as the Nalanda tradition, named after the famed Mahayana Buddhist university of ancient India.

Fearing that this knowledge might be lost as the Tibetan monastic system weakens, Jinpa decided to “translate, reformat, and recreate these Tibetan texts for better and more efficient use, and to make them part of the global literary tradition.” The Library of Tibetan Classics is an enormous project, a thirty-two volume set of translations of key texts. Nine have been published so far by Wisdom Publications, with the others in progress.

Jinpa also has what he calls a “hobby”—reforming classical Tibetan grammar to a more modern system to make it easier for future generations of Tibetans to retain their language. “Between the spoken and the written, there’s a big gap. I did a lot of research and wrote a book to help bridge this gap, and it’s now being used in some of the monasteries.”

A true Renaissance man, Thupten Jinpa says there is a drive that unifies the work he does in so many different fields: “It’s my belief that the preservation and dissemination of classical Buddhist knowledge and its practices, including compassion, is good for the world.” As Jinpa reflects on this, he pats the family dog, who has been sleeping at his feet. The dog wags its tail happily. This makes Thupten Jinpa smile. “Also, you know, I think I’ve just been plain lucky,” he adds, with a characteristic laugh.