Geshe Tenzin Tsepak. Photo courtesy Dhondup T. Rekjong.

In 2017, while pursuing my master’s degree at the University of British Columbia, I met Geshe Tenzin Tsepak. At that time, I only knew of him as an ordinary Tibetan Geshe-la at Tsengdok monastery in Vancouver. A few years later, I learned of his astonishing journey from Labrang in eastern Tibet to India in the early 1980s and asked him to sit down with me for a series of interviews about his travels and monastic studies.

Tenzin Tsepak was among the first Tibetan monks to arrive in India in 1982 and the first of the newcomers to earn a Geshe Lharampa degree, the equivalent to a Ph.D. in the West. To me, his story is a living treasure for understanding existence inside Tibetan cultural institutions in the early 1980s. At that time, Tibetans were rebuilding monasteries while the Tibetan government in exile in India was trying to sustain Tibetan culture in a foreign land. Tenzin Tsepak witnessed both the destruction and eventual rebuilding of Tibetan culture in the post-Cultural Revolution period. He was part of the preservation and reconstruction of Tibetan Buddhism in India and beyond.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a decade-long period of political and social chaos in China caused by Mao Zedong’s use of the Chinese masses to reassert his control over the Communist party. For Tibetans, it was a destructive force that massively affected religion, language, and culture, leaving indelible scars in individual and collective Tibetan memories.

Tenzin Tsepak doesn’t speak much unless you ask him. His answers are always short and precise, interrupted by a bout of coughing from time to time, hence why a cup of tea is always at his side. He is a humorous man who often laughs when sharing an interesting part of his narrative. In what follows, I let him narrate his experiences from Labrang to India. I have provided brief historical introductions to each step of his journey.

—Dhondup T. Rekjong

Rebuilding Labrang

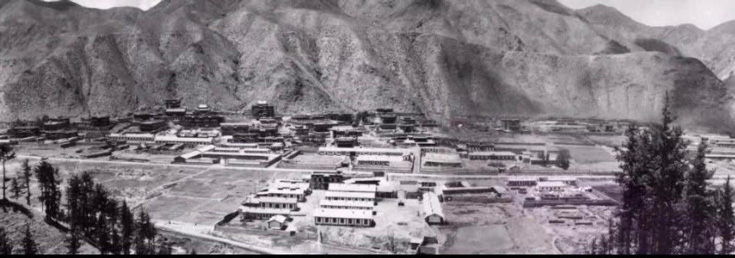

Geshe-la was a young boy in his hometown, Chentza, during the Cultural Revolution — one of the most destructive tragedies that happened after World War II. During this period, Tibetan scriptures and cultural sites were burned down, thrown into rivers, and otherwise banned or destroyed. There are not many Tibetans who documented that period and even fewer left who witnessed the historical calamity firsthand. Geshe Tenzin Tsepak was one of them. Right after the Cultural Revolution, so-called new liberal policies adopted by the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Chinese Communist Party Congress in 1978 partially relaxed the Party’s restrictions on Tibetan religious life, giving some Tibetans the leeway to rebuild their cultural sites from scratch. In 1980, Tenzin Tsepak decided to leave home for Labrang.

When I was 20 years old, I didn’t know what I wanted do with my life. My uncle was a monk in Labrang before the Cultural Revolution, and some relatives in my village encouraged me to take the same path of monkhood.

Taking their inspiration, I left home for Labrang, but I didn’t go there directly. I went to a neighboring town called Sangkok to see my uncle, who was staying at his patron family’s house. This family had sponsored his studies at Labrang monastery before the Cultural Revolution, and even bravely hid him at their house during that dark period. He was overwhelmed to see me and especially happy because I was hoping to become a monk under his guidance.

At the time, Labrang monastery was closed, but we believed it would reopen soon because of the new political climate in Beijing. After two months with my uncle’s patron family, we left for Labrang, but when we got there, there was no indication that the monastery would reopen. After almost 20 years, everyone there was hoping to see the re-opening and to resume their monastic studies. The former monks, now in their old age, were waiting for the senior religious masters and lamas to make a formal announcement.

We stayed at my uncle’s friend Aku Dulha’s place, which was in the upper region of the valley. He worked for the local government, but deep down he was very Buddhist. He was one of the first people receiving official documents prior to sharing them with the local Tibetans. Consequently, my uncle and I were the first people to hear new political news. Looking back, I believe there were many Tibetans who appeared to be working for the government in public but were preserving Tibetan culture in their private life.

Every day, new arrivals were pouring into Labrang to join the monastery, but they weren’t wearing monk’s robes. I heard that there were many Chinese government officials spying on Tibetans in the valley and reporting back to Beijing — they even warned the government to delay re-opening the monastery because they thought the influx of monks would bring the “old society” back, endangering the new socialist society they’d introduced.

From Aku Dulha, I heard a funny story about the letters of warning they sent back to Beijing. In Beijing, Panchen Rinpoche was the head of the central Religious Affairs Department. He and his colleagues received those complaints, but they didn’t share them with the Chinese leaders. As a result, the letters sent by officials in Labrang didn’t disrupt the re-building.

In the middle of August of 1980, while waiting for the re-opening, senior monks secretly started to receive transmissions, empowerments, and teachings from some prominent teachers, such as Aku Jigmey, Aku Palden, and Aku Luchoepa. They also secretly assembled to perform the restoring vow ceremonies. Under Aku Jigmey, I took both my novice and full ordination oaths in secret.

One day, at the beginning of 1981, one of the senior lamas, Alak Gongthang Rinpoche, made an announcement about recruiting new monks. He asked us to get permission from our local governments before joining Labrang monastery. I went back home to get a letter.

He later said that they were only allowed to recruit 50 monks in addition to the senior monks. There were already more than 200 new monks who wanted to join the monastery. Amongst those 50 monks, five monks were selected by each of the five monastic colleges and 25 were selected for the debate college. When I wasn’t selected, I was sad and discouraged, but Alak Gongthang advised us who didn’t get admission to apply the following year. He said that those who were not selected should not go back home or wear monk’s robes, but instead stay and study in the valley.

The monastic land was distributed amongst the senior monks to re-build their houses. There were around 100 senior monks at Labrang at that time. My cousin and I decided to build a house for my uncle, whose home had been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. It was impossible even to spot the ruins of the old house. It took us almost four months to build a new house for him with lumber we purchased in a neighboring village.

Looking at physical buildings in Labrang, there was barely anything left of the monastery except for the six main college halls — the Debate College, The Lower Tantric College, The Upper Tantric College, Kalachakra College, Medical College, and Hevajra College. They all looked intact from outside. I only had the chance to visit one. When I went to visit the Kalachakra College assembly hall, I found that the interior was filled with Tibetan woodblock prints and Buddhist canons, but nothing else. In particular, a wall of woodblock prints was piled up, one upon another, where normally monks would sit in rows, and a few statues could be seen in the interior space of the hall.

Those woodblock prints and Buddhist canons became a great help in later efforts to preserve Tibetan culture. I heard from the senior monks that before the Cultural Revolution, the head of the monastery, Jamyang Shepa, asked the monks to pile up all the woodblock prints in the main monastic college halls. I think he predicted the destruction to come from the east.

There weren’t many religious activities at the monastery while I was there, although the re-opening was progressing. My uncle usually went to prostrate to the statues of previous incarnations of Jamyang Shepa early in the morning, and then attended the morning prayers and spent the rest of his day reading Buddhist scriptures. My uncle was studying Vinaya at the time. Unlike him and other senior monks, those who were incarnate lamas were very busy giving empowerments, initiations, and teachings every day. Preserving the Buddhist lineages and teachings was their first priority after the Cultural Revolution.

Waiting to be admitted felt too long for a young monk like me, but my uncle asked me to be patient. In September 1981, we heard that Panchen Rinpoche was coming to Labrang. It was his first visit to the monastery, but it was very short. He publicly confirmed the political relaxation of religious studies and encouraged monks to practice openly. His visit gave senior monks and lamas some courage to be more active and travel restrictions were relaxed across Tibet.

In 1981, after Panchen Rinpoche’s visit, my cousin and I decided to leave Labrang for Lhasa. When I was at Labrang monastery, my uncle often told us about how amazing the monastic studies and culture was at the great monasteries there, such as Sera, Depung and Ganden. He said that the best students there don’t even take off their belts at night because they “burn the midnight oil.” My uncle’s admiration of Geluk monasteries in Lhasa and Panchen Rinpoche’s short visit inspired me to leave Labrang for Lhasa in October 1981.

Under a Tent in Ganden

Things were not entirely settled in Lhasa when Geshe-la arrived there in November 1981. In the historical capital of independent Tibet, Tibetans were in a bardo of fear and trust in the early 1980s, despite the Chinese Premier Hu Yaobang’s visit to Lhasa. He led a Working Group of the Party Central Committee (PCC) that inspected Lhasa from May 22 to 31, 1980 and then made his famous announcement of a six-point plan to solve many of the social, economic, and political problems faced in Tibet. It was one thing to make liberal commitments and another to implement them for the benefit of Tibetans.

My first impression of Lhasa was that there were no monks in the Barkor. My cousin and I were the first monks from Amdo many of the locals had seen — they called us Amdo Lamas. They came to touch our robes and asked us to bless them, having not seen monks for almost 20 years because of the calamity, seeing us provoked their emotions and historical memories. Barkor was mostly a residential area. There were very few restaurants with shops and just one that served Amdo cuisine. There were many Amdo butter merchants, but no pilgrims.

We went to visit the Jokhang Temple and Potala Palace. We were allowed to visit only Jowo and two chambers in Potala; other rooms were not yet open to the public. During our visit to the Jokhang, the Amdo butter merchants queued in a separate line because they had sacks of butter to offer.

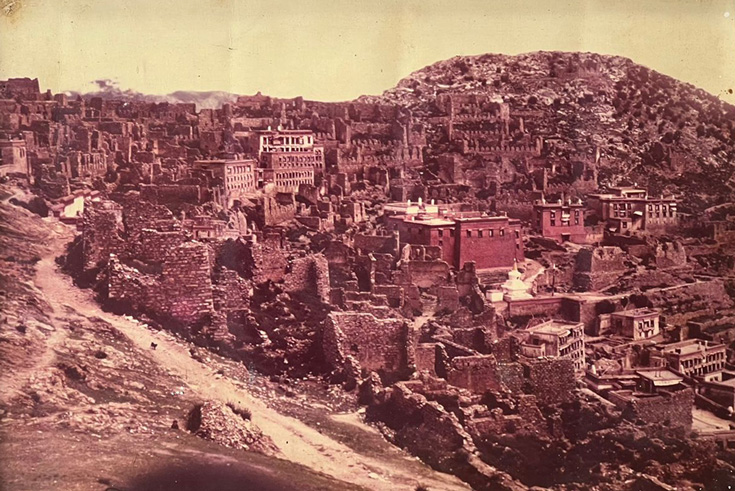

We went to join Ganden monastery, but the situation there was beyond imagination. The rebuilding work hadn’t even started yet. There was basically nothing functional except a few monastic halls, which were entirely locked and restricted to visit. All the former monk houses were in total destruction. I could only see some damaged walls that were still standing under the cold blue sky. We spotted some monks doing prayers under a tent, which covered the ceiling of a ruined house; only two sides of the house were built. There was a small altar in the middle and some worn mattresses laid around for the monks to sit on. Many monks were propitiating the guardian deity of Ganden, Dharma Raja Yama. There were more than 20 monks from Kham, some of which without robes because they were trying to clean up the ruins. Their leader Gen Gawo was kind to us. Looking back, the scene reminds me of Indian railway stations where ordinary folks rest and sleep during nights while waiting for their trains.

Gen Gawo encouraged us to stay if possible. He told us that Ganden is Tsongkapa’s seat monastery and Amdo monks were responsible for it during that difficult time. At the monastery site, there were two things to do: join the prayers under the tent or help clean up the ruins.

Since there was nothing to study or practice at the monastery, we went to visit other sacred places such as Tashi Lhunpo and Sakya, walking everywhere on foot. In the halls of Tashi Lhunpo monastery, the pictures of communist leaders Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin, and Mao were displayed. I was totally surprised because it was nothing like in Amdo. I thought there was more political restrictions in Lhasa but at the same time, I felt displaying their pictures was a strategic move to prevent further destruction.

While in Ganden, we did some prayers under the main tent during the day and at night slept under another tent shared by 20 monks. We all came there hoping to continue our studies and wait for the reopening of the monastery. Waiting was our only hope, because unlike in Labrang there was nothing ready for us to continue our studies. Ganden was more damaged than the Sera and Drepung monasteries in Lhasa.

In Lhasa during that time, it was impossible to talk about His Holiness the Dalai Lama or India, whereas in Labrang those conversations were held openly in public. Lhasa was still too traumatized to even mention the name of H.H. the Dalai Lama. If I talk about it to you, you might feel frightened — the situation was very different. However, Tibetans were wearing chubas, and there were a few ordinary Chinese in the Barkor. Since nothing was established at Ganden, my friends and I discussed going to India amongst ourselves without letting the others know.

Leaving Tibet

Since Ganden monastery wasn’t yet revived, Geshe-la and his friends decided to go to India.

In 1979, the Dalai Lama’s elder brother Gyalo Dhondup met Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, opening a new chapter in Sino-Tibet relations. As a result, between August 1979 and June 1980, the Tibetan government-in-exile dispatched four fact-finding delegations to Tibet. The Sino-Tibet border wasn’t yet open for Tibetans to visit their relatives inside Tibet or to come to India, but there were some positive expectations.

We had no idea how to reach India. We didn’t have a map or a guide or even anyone from whom to seek advice. We decided to go to Mount Kailash to see whether we were able to find a way to cross the border from there.

After a few days of traveling, we stopped at a restaurant in Shigatse. We ordered a large platter of momos, devoured it immediately, and ordered another. While we were finishing the second plate, we ordered a third. Three patrons entered; all were dressed in a way that we hadn’t seen before. I whispered to my friends that they might have some information about India because of their foreign look. We agreed to offer them our third order of momos. Since I was the eldest, I brought the momos to them and told them that we were full as we had two orders already. They were delighted to accept our momos. They asked me about the group and I told them that we were monks going for pilgrimage in the neighboring areas of Lhasa. I asked them where they were from, and they said they were from India and going to Amdo. I was happy to hear their Amdo dialects and felt an instant connection.

One of them asked me whether I had any plans to go to India. I lowered my voice and said yes. He seemed happy to hear that and asked his friend to draw a simple map for me. His friend took a napkin and drew a curved line and put three dots on the line. He drew a mountain, a stupa and a temple around each dot. He said they represent Mount Kailash at the border, Boudhanath stupa in Nepal, and Dharamsala in Northern India. He told me we just need to remember those three names in order to get to India safely.

He explained how we needed to tell people that we are going to Mount Kailash. When we got there, he said, we should tell people that we are going to Boudhanath stupa in Kathmandu, and from there we should say that we are going to Dharamsala. I was totally relieved by his advice. His simple map was eye-opening to all of us.

Before arriving at Mount Kailash, we stopped at a particular village. The village head hosted us for the night. Before we left the next morning, he announced to his villagers that we were Amdo lamas. The villagers came to us in the morning asking for blessings. We had nothing with us except our provisions and some books. To fulfill their wishes, I tore the cover cloth off our books and divided it into small pieces, which I distributed; they were overjoyed. Some of them even put the little pieces on their heads to receive blessings.

During that time, the border security wasn’t that restrictive. Our final stop in Tibet was Nyalam, which was a day long hike from Dam. We crossed the bridge in Dam. Interestingly, we didn’t realize that we got into Nepal until we met the Nepalese army at the other end of the bridge — they told us that we were in Nepal. We told them that we are heading to Boudhanath stupa, and they didn’t stop us.

Kathmandu

After two months travelling on foot, Geshe-la and his friends arrived in Kathmandu in 1982. The political situation in Nepal was relaxed and the country was supportive of Tibetan issues, an attitude which did not last. From 1959 to 1989, the Nepali government recognized Tibetans crossing the border as refugees. Although the King of Nepal stopped allowing Tibetan refugees to settle permanently in Nepal after their diplomatic rapprochement with China in 1989, under an informal “gentleman’s agreement” with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Nepal continued to permit the “safe passage” of refugees to India until 2008.

In Nepal, with a Tibetan businessman’s help, we safely arrived at Chapel bus station. I was surprised by the Nepalese rickshaw drivers there.

In Tibet, we often wave to drivers to stop their buses and cars, although there were few in my town. In Nepal, the rickshaw drivers waved to us. So, we thought riding was free in this country. I asked my friends to jump on a rickshaw, and a Tibetan woman also joined us. When we reached the Boudhanath stupa area, the driver asked us to pay, but we didn’t have a single penny in our pockets. I asked the Tibetan woman to help us and explained her our situation. She was happy to cover the fee and helped us to find our host monastery, Samten Ling.

We were allowed to stay at the monastery for almost a week. During that time, we visited Boudhanath stupa, Swayambhunath, and other sacred sites in the Kathmandu valley. The monastery was very helpful and made our stay happy and relaxing.

I remember that there were not many Tibetans in the Boudhanath stupa area. There were not many buildings around the stupa, like there are today. Just outside of the stupa was a farming area, but everything else was pretty much empty. When we went to the Boudhanath stupa area, Tibetans looked at us with curiosity. I thought that it was the first time they had seen newcomers from Tibet.

The abbot of the monastery brought us to the Tibetan Bureau office. There was no Tibetan reception center in Kathmandu yet. A staff member came out and told us that one of their female staff members was going to India, and she would take us there with her. We were not asked to register or do any paperwork. In the later years, newcomers from Tibet had to register at the reception centers in Nepal and India.

Meeting H.H. the Dalai Lama

When we arrived in Dharamasala, there was again no reception center. We were put in a government official’s apartment and asked to have our meals at the staff kitchen of the Tibetan government at Gangkyi.

The minister of security Alak Jigme was our main advisor. We basically did everything under his guidance. Alak Jigme said that Tibetans in exile hadn’t had a chance to see Tibetan people inside Tibet for almost 20 years – we were the first arrivals, and therefore a great resource for knowing the situation of Tibetans under China.

He arranged for us to meet His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The members of the His Holiness’s private office were overjoyed to see us. I was unable to understand everything the His Holiness said, but he was sharing our stories with others in the audience. I guess Alak Jigme already informed him everything we had told him about the situation inside Tibet. The meeting was emotional and encouraging.

His Holiness asked us to come to his smaller meeting room after the public event. In the absence of his secretaries, we spent almost 30 minutes with him and shared our stories and views of life inside Tibet. His Holiness asked whether we were going to stay in India or return to Tibet. We said we would like to stay. He asked whether we would like to join a school or a monastery; we said monastery. Then he asked which monastery, we said Ganden. He then encouraged us to go to South India. We were extremely relieved and happy.

The next day, we asked Alak Jigmey whether there was an opportunity to take our novice and ordination oaths again in front of His Holiness. In our presence, he phoned His Holiness and they discussed our situation. Alak Jigme told us that His Holiness would call back and confirm a date for us. Within a few minutes, His Holiness phoned. We were overjoyed and excited.

While we were in Dharamsala, we sent a letter to Gen Gawo in Lhasa, who had been helpful to us at Ganden. He circulated our letter around Lhasa. We later heard the news from Tibetans who arrived in India after us that the letter confirming our arrival in Dharamsala and our audience with His Holiness opened a door for a flux of new arrivals from Tibet. We even heard about our letter from monks who followed us years later. I think that maybe our letter to Gen Gawo in Lhasa was one of the major factors that gave courage to Tibetans, particularly monks, to come to India in the early 1980s. That political/religious migration continued until around 2008.

Under A Storehouse

When Geshe-la arrived in South India in 1982, the monasteries were yet to be built. One of the challenges that the Dalai Lama’s government faced in India was sustaining Tibetan monastic studies in a new country, with only the sky and earth as their friends. The Dalai Lama worried that the scholarly traditions of Tibet’s great monasteries would be lost unless the monks and nuns could continue their education. He negotiated with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to establish a nonsectarian educational institution for 1,500 monks and nuns in a former British prison camp in Buxa Duar, a remote area of West Bengal. Many of these scholars and students met at Buxa for the first time and stayed nearly ten years before sorting out permanent places to build monastic institutions. Thus, Buxa played an important role in the preservation of Tibetan Buddhism and its transmission around the world. The first batch of monks departed for South India in November 1969, when the Karnataka state government gave them land for two large settlements.

At Ganden, the monks were assembling and doing their prayers under the roof of a local storehouse. The back of the storehouse was filled with piles of dried corn, and only the front side was used by the monks. I don’t remember whether we had a proper altar. The only monastic characteristic was the steeple of the storehouse.

There was a plan to build the monastic hall, and immediately after our arrival, started building it. Within two years, the first monastic hall was established. There was a saying amongst the monks during that time that our monastic hall was “built by deities, not monks” because of our poor situation.

There was no systematic education except morning prayers and evening studies. During the day, we worked in the field growing corn and rice. The process of farming was long; we needed to plough the field and then level the rough earth, then plant the rice and harvest it, and then separate the rice from chaff. I once calculated the number of days we got per year to study — each year we had less than four months to study during the first few years.

Our monastery had more senior monks and fewer young monks. I think there were around 150 monks in total at that time. We also suffered from a poverty of books. When we were studying the commentary of Pramanavartika, we shared one book between the upper class and lower class according to what chapters we were reading.

In 1985, H.H. the Dalai Lama came to South India to give a Kalachakra empowerment. At the teaching, H.H. encouraged the local Tibetans to help the monks; H.H. jokingly said the local Tibetans have oily faces, unlike the monks, whose faces were dusty. From then onwards, we began receiving donations from the locals and beyond.

Donations helped the flourishing of Buddhist studies at Tibetan monasteries in South India and beyond. Geshe la achieved his Geshe Lharampa degree in 1999 after studying the core texts, such as collected topics, paramita, madhyamaka, abhidharma, and vinaya, for almost 20 years. Amongst the newcomers, he was the first monk to receive the Geshe Lharampa degree. Other newcomers who also achieved this degree, received it with a permission either from the department of religion in Dharamsala or the Dalai Lama. None of them had done the 6-year exam. However, that special degree was later abandoned entirely.

After his degree, Geshe-la taught Buddhism in South India and other parts of Asia for many years. He moved to Canada in 2017, where he currently awaits permanent resident papers.