Yangshan’s “High and Low”

Main Case

One day Zen master Huiji of Yangshan joined his teacher Guishan in plowing the rice field.

Yangshan said, “Master, this place is low. How can I level it with the higher place?” Guishan said, “Water is level, so why not use water and make the entire field level?” Yangshan said, “Water is not necessary. Master, high places are level as high and low places are level as low.” Guishan approved.

Commentary

The House of Guiyang is like this, parent and child complementing each other’s actions. Yangshan’s question is just an excuse to interact with his teacher. How can he not know that high is perfect and complete just as it is, and low is perfect and complete just as it is? But say, is there some Zen truth here that is being revealed?

Although you may speak of the absolute and the relative as if they were two things, the truth is that they are in fact one reality. In one there are the ten thousand things, in the ten thousand things there is only one.

Verse

Each and every thing abiding in its own dharma state completely fulfills its virtues. Each and every thing is related to everything else in function and position.

—From The True Dharma Eye, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and John Daido Loori; commentary and capping verse by Daido Loori

Guishan and Yangshan were master and disciple in ninth-century China. Together they formed the Guiyang school, which was one of the five main schools of Zen in China. There are quite a number of koans with the two of them displaying a very close spiritual relationship. Here they’re plowing the field, working together, examining the dharma—our lives should be like this.

Yangshan said, “Master, this place is low. How can I level it with the higher place?” We tend to see the whole world in terms of high and low. Seeing things this way, we usually want to get to the higher place, and so we have various ranks, positions, and titles to establish exactly what ground we’re on. That way everyone knows where we stand and we know everyone else’s place. This is the tyranny of possessing an identity. We worry about how our identity measures up. Are we inferior or superior, ahead of the rest or falling behind? But as Daido Roshi says, “This dharma is equal—no high, no low.” That is, the true world doesn’t function in terms of high and low; it just moves in accord with its nature. High and low is the functioning of our conditioned mind.

In our formal training, we employ various positions and titles that appear to resemble worldly positions and titles. We do this so we can realize they are void of any kind of inherent truth—no position or hierarchy can endow someone with superiority. Then, seeing this clearly, we can use these positions for skillful purposes; we can use them knowingly. Yet how much suffering, how much human destruction—past, present, and future— arises from a view that places everything in a relative position? This is the mind that dominates and subjugates the Earth and everything on it for its own convenience. This mind confuses us, giving rise to the idea that it is our place and our right to subjugate. That’s why we examine the many ways those false assumptions get played out. And what we realize is how frequently our behavior comes down to habits of convenience and our tendency to be lazy. But ours is not a practice of laziness.

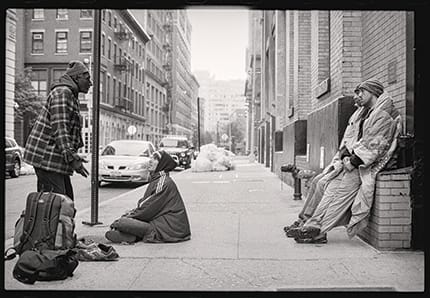

New York City is a perfect place to notice how quickly our mind turns toward those sharp and decisive discriminations, because everywhere we look we see the vast spectrum of humanity. We can practice just observing the mind as we walk down the street and pass people by, or as we sit on the subway or stand at a counter. What do we perceive? Attraction, repulsion, formations of mind, unreal mental constructions, and thoughts and fantasies that we take as the truths about others. Yet all of this is our conditioned mind. We say to ourselves, “This person is smart; that person is stupid. This person is lazy; that person works hard. This person is interesting; that person is boring.” We get so caught up in our ideas about others that we silently judge them without ever really seeing the person who is right there in front of us.

One of the first years that I was at our Brooklyn Temple, I went out one Sunday morn- ing before sunrise for a run and saw that there was a homeless fellow on the front sidewalk who had bags of gear spread out all around him. In addition, a limb had broken off the tree in front of the temple and fallen on the sidewalk during the previous night’s storm, so the whole sidewalk was a mess. I went over and said good morning and asked what was up. He said he was organiz- ing his stuff. I said, “You know, people are going to be coming soon for our Sunday service, so all your personal things here are going to be a bit of a problem.” He said, “Don’t worry, Reverend, I’ll have it all cleaned up.”

So I set off on my run and went around the block figuring I’d swing back to see how it was going. As I ran past, he saw me and called out, “I’m on it, Reverend!” I said, “Okay, great.” When I came back a while later, the sidewalk was immaculate. All of his gear was carefully organized and meticulously packaged. Not only had he taken care of his own things, but he had also broken up all of the wood from the fallen branch into same-sized sticks and tied them into a bundle with a piece of cloth. He had then attached the bundle to a branch of the tree and on a piece of cardboard written a note that said, “Dear Sanitation Workers, just pull this string and this wood will drop out and you can haul it away.” I kid you not. If we were a business, I’d have hired the guy.

In that moment, my sense of who this person was went through a transformation. After initially regarding this man as someone on lower ground, suddenly my view of him was raised. Our initial expectations of someone can be defied and changed by experiencing them in a new way, which enables us to see how our fixed ideas are false. Experiences like this offer a certain kind of medicine: they give us pause, teach us not to be so quick, and help us understand that superficial appearances are just that.

But this is still working on the surface, because this kind of opening is dependent upon having our expectations challenged. What if I’d come back from my run and all of his gear was still laid out and he hadn’t done a thing? Or what if he hadn’t been so courteous? What ground would I have put him on then? How quickly the mind assumes certainty and mastery of the situation. There are profound, seemingly infinite implications to this. Call it human history. Call it the endless cycle of birth and death. Call it the ceaseless war of humankind, the ever-waxing-and waning gap between those who have and those who don’t, the perennial and ever-evolving forms of boundary and division, forms that include and exclude, that become the cause and justification for how we subjugate and dominate.

I read an article recently about a study on gender bias in hiring practices. The researchers sent a resumé to the science departments of six highly regarded research universities. Every application was exactly the same, except on some the applicant was named John and on others the person was named Jennifer. They found that, on average, John was much more likely to be recommended for hiring and offered a larger salary. So here we have exactly zero personal information—not even a photograph—just the abstract symbols contained in a name. And the consequences of that bias and discrimination, that sense of certainty, connects directly to a human being and helps shape what his or her life will be. For John, the door may swing wide open; for Jennifer, it’s a smaller, meaner world.

I remember the first time I walked into this monastery. I saw a grand hall; I saw the person who was to become my teacher; I saw practitioners, people who looked a lot like me; I saw a place of potential. I didn’t see anything that made me ask myself, “Is this my place? Do I belong here?” That didn’t happen, and I didn’t even notice that it didn’t happen. The fact that I didn’t experience a barrier is a kind of privilege. I didn’t have to think about it. However, because our sangha is still largely white, others who are not white-skinned may walk into this hall and have a different experience. They may be stopped by that very question, “Do I belong here?”

So, what is my role in that? Am I perpetuating suffering or working to bring it to cessation? We talk so much about alleviating suffering, and we need to be careful that it doesn’t become abstract. “I vow to alleviate the suffering of all sentient beings.” What suffering beings are we talking about? We’re talking about you and me. We’re talking about every living being.

Guishan says, “Water is level, why don’t you use water to level it?” Water moves freely; it’s not fixed. Cool it and it turns to ice; heat it and it turns to gas. When it’s quiet and gentle, its murmurings can put a baby to sleep; in its wrath and fury, it can destroy cities and landscapes. Not being fixed to any state, it can both give life and destroy it.

In Daido Roshi’s poem accompanying the Main Case, he says that each thing abides in its own dharma state. What is the “water” that Guishan is speaking of? What is it that levels all differences, equalizes all inequalities, dissolves all distances? In the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Buddha speaks of the world as a Buddha-field, a place of splendor and perfection. He also said that some living beings can’t behold the splendid display of virtues of this Buddha-field due to their own ignorance and confusion. It’s not that they don’t have the capacity to see it clearly, but rather they aren’t able to see it yet.

It’s neither the fault of the world nor the eyes. Hearing this, Shariputra says, “As for me, I see this great Earth with its highs and lows, its thorns, its precipices, its peaks, its abysses.” An elder disciple says, “The fact that you see such a buddha-field as this as if it were so impure is a sure sign that there are highs and lows in your mind.” This is true, but our beliefs in those highs and lows are conditioned; we weren’t born with them. If we were born with the belief that high and low exist as an absolute truth then we’d be truly imprisoned by it; practice and enlightenment would not be possible.

When we free ourselves of our discriminating mind, our constantly judging and comparing consciousness, we can begin to see things without hindrance or prejudice. Yangshan says, “Master, water is not necessary. High places are level as high and low places are level as low.” Of course Guishan knows this. As Daido Roshi says, “The old master is just willing to go along and see what this all comes down to.” The low place is low in and of itself; it is free of low and high. The low place is not fooled by its place. To realize and actualize this is to live amid the highs and lows, light skins and dark skins, female and male bodies of our world without being deceived by such differences, which can lead to so much suffering.

Dogen wrote a poem about this koan:

Before the mountains, an ownerless wild land,

Up and down, high and low are left to forage.

Wishing to judge square or circle, or figure bent and straight,

From east, west, south, and north, a single green seedling.

— From Dogen’s Extensive Record, translated by Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

To give up all ownership takes great trust. To be that ownerless wild land yourself is not just a matter of mechanically letting go. It’s a great leap into the water of our original nature. Vimalakirti said that if we want to heal our sickness, we have to give up our egoism and possessiveness. But who wants to give up their affliction if it comes in the form of privilege? Even our disadvantage or subjugation becomes conditioned. The person who is held by the jailer becomes beholden to the jailer. So to eliminate egoism and possessiveness we have to free ourselves from duality, from being fooled by the appearances of inside and outside, external and internal, high and low. Vimalakirti says this means we must not deviate, not fluctuate, not be distracted. But not be distracted from what? Vimalakirti says from equanimity. Or you could call it profound sanity. We must not deviate nor be distracted from what is true. What does that mean? It means that in the moment when we look and our mind instantly begins to form a clear and certain image, we see that construction. It is only then that we can recognize its destructiveness. We see how in that moment a whole person—who is as vast as the universe—becomes an object in our mind. And you know what we do to objects; we throw them away when we have no more use for them. The remedy for such violence is to see with the unbiased eye of wisdom what is directly before you.

When we see that each person, each circumstance, abides in its own state, we realize that whether or not it satisfies our sensual desires is no longer the most important thing. In our taking care of the Earth, we can move beyond doing so because we need to for our own benefit. That view is still not regarding the Earth as sacred unto itself. It’s not because of what you do for me that I should see you and regard you as a fully free and complete human being abiding in your own dharma state, but rather simply because you are. If I don’t or can’t yet see that, my vow is to practice so I can see it. My vow is to see how you are interdependent with everything. That includes me. You and I are interdependent. That means that, even if I don’t yet understand how, in your arising I come into being. In your cessation, I cease to be. When you are disregarded, my humanity is injured. When you are liberated, my happiness is boundless. Thus on an everyday level, we have a deep and vested interest in each other.

Perhaps this is the great imperative of our present time. Through practice we can discover how to allow the mind to find its natural equality. When mind ceases to create divisions and boundaries, then the world is without divisions and boundaries. Going further, we see that practice has not changed the nature of this world one inch. It doesn’t help make highs and lows equal; it shows us their basic equality, which has been present all along. Realizing this, we can appreciate and enjoy the tall mountain as tall, and the low mountain as low.