Like the great Zen ancestors Bodhidharma and Huineng, Nyogen Senzaki has, in the fifty years since his death, become something of a Zen legend—despite the fact that he lived in obscurity and spoke of himself as “a mushroom, without a very deep root, no branches, no flowers, and probably no seeds,” and as “a lone cloud floating freely in the blue sky.” 1 These five decades since Nyogen Senzaki’s passing have seen the emergence of Zen in the West not merely as an intellectual pursuit, but as a rigorous and life-changing daily practice. This emergence is in no small way Nyogen Senzaki’s legacy. While D. T. Suzuki brought the philosophy and culture of Zen Buddhism to America, it was Nyogen Senzaki who taught Zen as a steady, disciplined, unromantic yet transformative path of everyday life.

Nyogen Senzaki came to America, in part, because he had become disenchanted with modern Buddhism in Japan. As Eido Roshi explains, “He wanted to revive it in fresh soil.” Soon after he arrived in America in 1905, his teacher, Soyen Shaku, told him to remain anonymous and not to teach for at least seventeen years. He complied, supporting himself with whatever work he could find while struggling to learn English during the few hours he wasn’t working. Then after seventeen years, he began to present lectures on Buddhism whenever he could save enough money to rent a hall.

Certain themes recur throughout Nyogen Senzaki’s koan commentaries, talks, essays, poems, and letters: “Block the road of your thinking,” he tells us again and again. “Give the uppercut to your own dualistic ideas.” The simpler the better, he emphasizes; no word is best of all. We must continually strive to actualize the truth of Zen for ourselves, since realization “will not come to us by luck, as in a lottery” (Case Twenty-two of The Gateless Gate). If we are filled with “emotional pining” for something outside, for someone else’s understanding, we are cut off from our own inner wisdom. He notes that real Zen teachers never give anything; rather, they take away whatever their students are attached to.

Nyogen Senzaki died in 1958 at the age of 81. He left his manuscripts to his friend Soen Nakagawa Roshi, and he in turn passed them to his dharma successor, Eido Roshi. Selections of these writings and teachings were published in Namu Dai Bosa (1976) and Like a Dream, Like a Fantasy (1978 and 2005).

Now a third volume of Nyogen Senzaki’s teachings and writings has been published by Wisdom Publications to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his death. Eloquent Silence offers previously unpublished talks, commentaries, and letters, including Nyogen Senzaki’s commentary on The Gateless Gate (Mumonkan in Japanese), based on talks given to his American students from 1937 to 1939. Here we offer this important Zen master’s commentary on the introduction and first four koans of The Gateless Gate, which are among the most famous in all of Zen. The Gateless Gate was recorded by the Chinese Zen master Mumon Ekai (1183–1260), more commonly known as Mumon.

Mumon’s Introduction

Bodhisattvas: We now begin to study our text.

Mumon says in his Introduction:

Zen has no gates. The purpose of Buddha’s words is to enlighten others; therefore, Zen is gateless. Now, how does one pass through this gateless gate? There is a saying that whatever enters through the gate is not the family treasure. Whatever is produced by the help of another will dissolve and perish.

In the Bible we often see such an expression as, “That which the Lord has declared unto his prophets should come to pass….” This is a distorted view of the teachings of Revelation. The young stage of a religious mind always lingers around such an idea. One thus has to have a Supreme Being, and the agency of prophets. The compilers of old scriptures had to work hard to satisfy those childish minds, and thus stitched together the ragged pieces of old traditions and legends.

Zen has nothing to do with such antiquities. You are here to meditate only because you want to know your true self. No agent of a Supreme Being provoked you to come. No scriptures enticed you to study meditation. As Mumon says, “Zen has no gates.” All of you have gathered here by your own will. The purpose of Buddha’s preaching is to dispel the clouds of delusion and to allow the sun of enlightenment to blaze forth from your own mind. Just as medicines are prescribed by a doctor according to the nature of the sickness, the teachings are provided by Buddha according to the condition of the disciple’s mind. Therefore, the essence of the teaching has no particular form or mold. This is what Mumon means in saying, “Therefore, Zen is gateless.”

In his time, all students of Buddhism understood that Zen is the essence of Buddhism, not a school or a sect of it. Mumon quotes a Chinese saying, “Whatever enters through the gate is not the family treasure.” And to make the meaning clear, he adds another saying of Buddhism: “Whatever is produced by the help of another is likely to dissolve and perish.” In the West you say, “Heaven helps those who help themselves.” Buddhism says, “One creates heaven and earth by oneself.” You must discover your own family treasure within yourself. I am a senior student to you all, but I have nothing to impart to you. Whatever I have is mine, and never will be yours. You may consider me stingy and unkind, but I do not wish you to produce something that will dissolve and perish. I want each of you to discover your own inner treasure.

Mumon continues:

Even such words are like raising waves in a windless sea or performing surgery upon a healthy body. If you cling to what others have said, and try to understand Zen through explanations, it is as though you are trying to hit the moon with a pole, or scratch your itchy foot from the outside of your shoe. It is not at all possible.

Those who understand Zen need not listen to Mumon or anyone else. But most students have something lurking in their minds, something that is bound to become a harmful parasite: a feeling of dependence upon others for their own growth. These students need sharp and emphatic encouragement, not soft and kind words.

The following part of Mumon’s Introduction will be understood without comment. I will offer it here and stop raising waves in a calm sea, or performing surgery upon a sound body.

In the year 1228, I was giving Dharma discourses to the monks in the temple of Ryusho, City of Toka, in the Province of Onshu, and at their request I retold old koans, endeavoring to inspire their Zen spirit. I meant to use the koans as one uses a piece of brick to knock at a gate: after the gate is opened, the brick is useless and is thrown away. Unexpectedly, however, my notes were collected as a group of forty-eight koans, together with my comments in prose and verse on each, although their arrangement was not in the order in which I spoke about them. I have titled the book the Mumonkan (Gateless Gate), and offer it to students to read as a guide.

If you are brave enough and go straight ahead in meditation, you will not be disturbed by delusions. You will attain Zen just as did the ancient masters of India and China; perhaps even more so. But if there is a moment’s hesitation, it is as though you are watching from a small window for a horse and rider to pass by—in a blink of your eye, they are missed.

Mumon ends the Introduction with his verse:

The great Way has no gate;

Thousands of roads enter it.

When one passes through the gateless gate,

One walks freely throughout heaven and earth.

Soon we will begin a week of seclusion in commemoration of Bodhidharma, from the third of October to the ninth. This is a fine opportunity for all of you to practice Zen with self-determination. Let us see what we can do for attainment.

Case One: Joshu’s Dog

A monk asked Joshu, “Does a dog have buddhanature or not?” Joshu answered, “Mu.”

Bodhisattvas: The first koan in The Gateless Gate is “Joshu’s Dog.” This koan is usually the first one given to the Zen student. Many masters in China and Japan entered Zen through this gate. Do not think that it is easy just because it is the first. A koan is the thesis of the postgraduate course in Buddhism. Those who have studied the teachings for twenty years may consider themselves scholars of Buddhism, but until they pass this gate of “Joshu’s Dog,” they will remain strangers outside the door of buddhadharma. Each koan is the key of emancipation. Once you are freed from your fetters, you do not need the key anymore.

A stanza from the Shodoka (“Song of Realization”) goes:

The wonderful power of emancipation!

It is applied in countless ways—in limitless ways.

One should make four kinds of offerings for this power.

If you want to pay for it,

A million gold pieces are not enough.

If you sacrifice everything you have, it cannot cover your debts.

Only a few words from your realization are payment in full,

Even for the debts of the remote past.

You can get this power of emancipation when you pass “Joshu’s Dog.” Your answer to this koan will be your payment in full, even for the debts of the remote past.

The great Chinese Zen master Joshu always spoke his Zen, using a few choice words, instead of hitting or shaking his students as other teachers did. I know that students who cling to worldly sentiments do not like the rough manner of Zen. They should meet our Joshu first, and study his simplest word, “Mu.”

Each sentient being has buddhanature. This dog must have one. But before you conceptualize about such nonsense, influenced by the idea of the soul in Christianity, Joshu will say “Mu.” Get out! Then you may think of the idea of “manifestation.” Fine word! So you think of the manifestation of buddhanature as a dog. Before you can express such nonsense, Joshu will say “Mu.” You are clinging to a ghost of Brahman. Get out! Whatever you say is just the shadow of your conceptual thinking. Whatever you conceive of is a figment of your imagination. Now, tell me, has a dog buddhanature or not? Why did Joshu say “Mu”?

Mumon’s Comment

To realize Zen, one has to pass through the barrier set up by the patriarchs.

Do not think that the barrier is in the book. It is right here in front of your nose.

Enlightenment is certain when the road of thinking is blocked.

Meditation blocks the road of thinking.

If you do not pass the patriarchs’ barrier, if your road of thinking is not blocked, whatever you think, whatever you do, will be like an entangling ghost.

You are not an independent person if you do not pass this barrier. You cannot walk freely throughout heaven and earth.

You may ask, what is the barrier set up by the patriarchs? This one word, Mu, is it. This is the barrier of Zen. If you pass through it, you will see Joshu face-to-face. Then you can walk hand in hand with the whole line of patriarchs. Is this not a wondrous thing? If you want to pass this barrier, you must work so that every bone in your body, every pore of your skin, is filled through and through with this question, What is Mu? You must carry it day and night.

Didn’t I tell you it is not an easy job? Don’t be afraid, however. Just carry the koan, and ignore all contending thoughts. They will disappear soon, leaving you alone in samadhi. Do not believe Mu is the common negative. It is not nothingness as the opposite of existence. Joshu did not say the dog has buddhanature. He did not say the dog has no buddhanature. He only pointed directly to your own buddhanature! Listen to what he said: “Mu.”

If you really want to pass this barrier, you should feel as though you have a hot iron ball in your throat that you can neither swallow nor spit up.

Don’t be afraid; he means you should shut up, and cut off even the slightest movement of your intellectual faculty.

Then your previous conceptualizing disappears. Like a fruit ripening in season, subjectivity and objectivity are experienced as one.

There you are, in samadhi.

You are like a dumb person who has had a dream. You know it, but you cannot speak about it. When you enter this condition, your ego-shell is crushed, and you can shake the heavens and move the earth. You are like a great warrior with a sharp sword.

Neither Japan nor China has such a warrior; therefore they have to fight each other.2

Cut down the buddha who stands in your way.

What Mumon means here is complete unification.

Kill the patriarch who sets up obstacles.

This is an expression in Chinese rhetoric, meaning once you become a buddha, you have no more use for buddha. Some Japanese blockhead could not understand such a peculiar expression, and many other quaint Chinese terms as well, and took them all as invitations to stir hatred. This is one of the causes of the conflict between China and Japan. Ignorance is not bliss; it is a terrible thing.

You will walk freely through birth and death. You can enter any place as if it were your own playground. I will tell you how to do this. Just concentrate all your energy into Mu, and do not allow any discontinuity. When you enter Mu and there is no discontinuity, your attainment will be like a candle that illuminates the whole universe.

Discontinuity may be allowed at first while you are engaged in your everyday work, but when you are meditating in the zendo or in your home, you must carry on with this koan, minute after minute, bravely. Our seclusion week is an opportunity for you to engage in this sort of adventure. After you train yourselves well, then even in the midst of your everyday work you will find your leisure moments filled with the koan.

Mumon’s Verse

Does a dog have buddhanature or not?

This is the most profound question.

If you say yes or no,

Your own buddhanature is lost.

Case Two: Hyakujo’s Fox

Hyakujo was delivering a series of Zen lectures. An old man attended them, unnoticed by the monks. At the end of each talk, when the monks left the hall, he would follow them out. But one day he remained, and after the monks had gone, Hyakujo asked him, “Who are you?” The man replied, “Many eons ago, I was a human being. This was in the time of Kashyapa Buddha (the prehistoric Buddha), and I was a Zen master living on this mountain. One day a student of mine asked me whether or not an enlightened person is subject to the law of causation, and I foolishly replied, ‘An enlightened person is not subject to the law of causation.’”

“For this answer, evidencing a clinging to the absolute, I became a fox for five hundred rebirths, including this present one. Will you free me with a Zen word from this prison of a fox’s body? Please tell me your answer. Is an enlightened person subject to the law of causation?”

Hyakujo replied instantly, “An enlightened person is one with the law of causation!”

At these words, the old man was enlightened, and cried out, “Now I am free!” Paying homage with a deep bow, he said, “I am no longer a fox, but I must leave this body in my dwelling place behind this mountain. Please give me a monk’s funeral.” Then he disappeared.

The next day, Hyakujo told the head monk to make preparations for a monk’s funeral. “But no one has been sick in the infirmary,” wondered the monks. “What can this mean?”

After dinner, Hyakujo led the monks out of the dining hall and around the mountain. There they found a cave. Taking his staff, Hyakujo poked around in the leaves at the cave’s mouth until he uncovered the body of a fox. He then performed the ceremony of cremation.

Later that evening, Hyakujo related the story to the monks. Obaku, after listening carefully, asked Hyakujo, “I understand that a certain person, many ages ago, gave a wrong answer. For this he was turned into a fox for five hundred rebirths. Now please tell me—if some modern master, being asked many questions, always gives the right answer, what then?”

“If you will come up here to me,” Hyakujo replied, “I will tell you.”

Without hesitating, Obaku got up and hurried to his teacher, giving him a resounding slap on the cheek, for he knew that this was the answer his teacher intended for him.

Hyakujo clapped his hands and laughed aloud at this discernment. “I thought the foreigner had a red beard,” he cried, “and now I know it!”

Bodhisattvas: It is probable that Hyakujo made up this tale himself, in order to impress on his monks the authority of the law of causation. He chose his material carefully, so as to best appeal to their level of understanding.

At the Flower Festival this year, I said, “Every action brings its own results in the material world, in the realm of the mind and in society. Cabbages and kings, rich men and paupers, wise birds and stupid asses—none can break the law of causation.” This is my answer to this koan. Enlightened person or unenlightened person, it makes not the slightest difference.

The person who understands the law is wise enough; the person who knows to beware of the law can live righteously. One who does as one pleases, yet stays within the bounds of the law, is a great sage; that one is an enlightened person.

Those who believe in the power of the church or priestcraft to erase their sins are all foxes. When they believe the church or priest is not subject to the law of causation, they expose their inability to live congenially within the law. Their children will do as they do, and society will imitate them. This is the power of their evil karma.

Obaku was the best disciple of Hyakujo, and knew what his teacher meant. What he was asking was, “Where is the person who is always one with the law of causation?” Hyakujo did not dare say, “I am that person.” Instead, he would have said, “You are the one, my dear Alfonse,” and would have slapped his disciple’s face. But Obaku prevented this by slapping his teacher’s face: “You are the one, my dear Gaston.”3

Hyakujo then clapped his hands and laughed. “I thought the foreigner had a red beard, and now I know it.”

Mumon’s Comment

“An enlightened person is not subject to”—How can this answer make the monk a fox?

Because he postulates an enlightened person, and separates himself from the law of causation.

“An enlightened person is one with the law of causation”—How can this answer emancipate the fox?

When you are enlightened, you can do as you please; yet you will always live within the law.

To understand this clearly, you must have only One eye.

That’s what Mumon says, but it’s too late in this zendo. All who have attended this class know very well, “The eye with which I see God is the very eye with which God sees me!” Mumon, Mumon, are you trying to sell the “Extra, extra!” of the day before yesterday?

Mumon’s Verse

Subject to or not subject to?

The same die shows two faces.

Not subject to or subject to?

Both are mistaken!

In Zen, thinking and acting must be without an instant’s hesitation, otherwise your action or word will be an uncertain gamble.

Case Three: Gutei’s Finger

Whenever he was asked a question about Zen, Gutei raised his finger. A young attendant began to imitate him. When anyone asked the boy about his master’s teaching, the boy would raise his finger.

Gutei heard about the boy’s mischief. He seized him and cut off his finger. The boy cried and began to run away. Gutei called out to him. When the boy turned his head, Gutei raised his finger. At that, the boy was enlightened.

When Gutei was about to pass from this world, he gathered his monks around him and said, “I attained my one-finger Zen from my teacher, Tenryu, and throughout my whole life, I have not exhausted it.” Then he passed away.

Bodhisattvas: In the time of Gutei, the Chinese government persecuted Buddhism, destroying 40,000 Buddhist temples and canceling the ordination status of 260,000 monks and nuns. This took place in 845 CE; the tyrannical rule lasted for twenty months. As a monk, Gutei lost his temple home. He hid himself in a remote mountain, begging for his food secretly among the villagers. One evening a nun came to his shelter and walked around him three times with her traveling staff without taking her hat off. It was very impolite to act that way at a monk’s shelter. She made it clear that she considered him a stone image, not a living monk. Gutei commanded her to take off her hat. The nun said, “If you are not a stone image, say a word of Zen, and then I will properly pay you my respects.” Gutei had never attained Zen; therefore, he could not say a word. The nun called him a stupid monk, and went away. Gutei was ashamed of himself to no small degree. He made up his mind that he would undertake a journey through which he might attain understanding. Before he could start out, however, he was visited by an old monk. Gutei expressed his shame and resolve, frankly, in a man-to-man talk. The old monk then raised his finger. Seeing this, Gutei was enlightened. The old monk was Tenryu, a great teacher of that time.

Although the Chinese government’s persecution resulted in the worst circumstances for the Buddhist establishment in its history in China, it created the opportunity for good monks and nuns to set out on pilgrimages. Gutei, too, caught his chance at this time of oppression. He sensed keenly that the opportunity for realization is rare and noble. This was the reason why, in our present story, he cut off the boy’s finger.

An imitation of the teaching seems at first rather innocent, but if it is not nipped in the bud, it will grow into the ugly weed of religious complacency, or into the troublesome weed of hypocrisy. To open the gate of realization, one must block off one’s road of conceptualization. Gutei seized the boy and cut off his finger. The boy cried and began to run away. It was too sudden for the boy to think of anything; there was only the pain. At that moment, Gutei called for the boy to stop. The boy turned his head toward Gutei, and the master raised his finger. There! With his road of thinking blocked, the boy could be enlightened.

This koan not only teaches you to realize Zen for yourself, but also shows you how to open the minds of others and let them see the truth as clearly as daylight. The power of Zen that Gutei received from Tenryu was not merely the act of raising a finger; it was the means to enlighten others. Therefore he said on his deathbed, “I attained my one-finger Zen from my teacher, Tenryu, and throughout my whole life, I have not exhausted it.”

Mumon’s Comment

The enlightenment that Gutei and the boy attained has nothing to do with the finger. If you cling to the finger, Tenryu will be so disappointed that he will annihilate—another Chinese expression; we should probably use the word “disown,” or “expel”—Gutei, the boy, and you.

Mumon’s Verse

Seeing a picture of Bodhidharma, Wakuan asked, “Why does that son of a western barbarian have no beard?”

Gutei cheapens Tenryu’s teaching

Emancipating the boy with a knife.

Compared to the Chinese god who divided a mountain with one hand,

Old Gutei is a poor imitator.

A Chinese myth tells us that the Yellow River at first could not run toward the east, as there was a great mountain in the way. A god came to help, and divided the mountain into two parts, so that the water could run through. If you look carefully at those two mountains, you will find the fingerprints of this god. Such a story! Zen never asks us to believe in miracles, but we Zen students perform miracles without knowing it ourselves. Didn’t I give you a koan in this seclusion: “After you have entered into the house, then let the house enter into you.” Now, show me how you accomplish this trick! Those who are still working on this koan: have a cup of tea and go home. You will sleep soundly tonight.

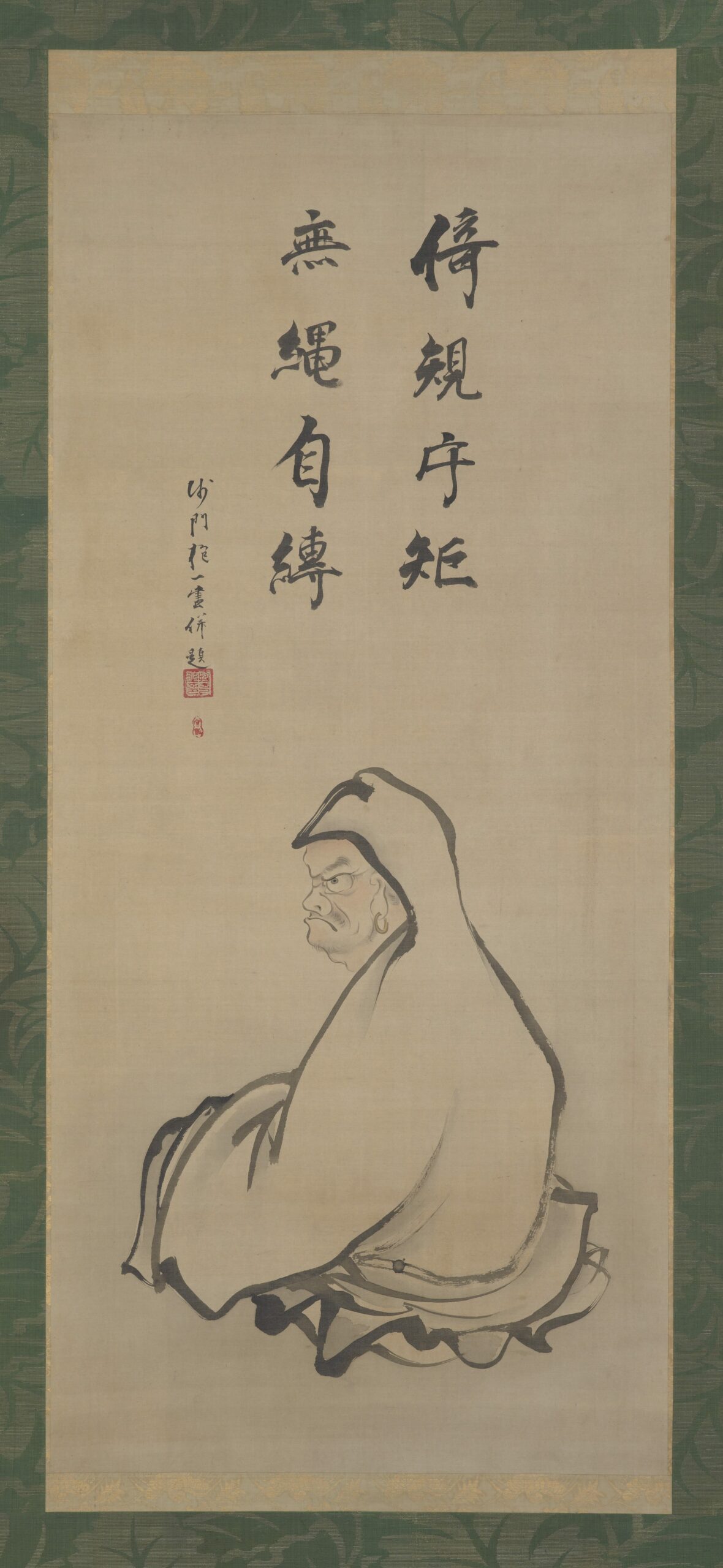

Case Four: A Beardless Foreigner

Seeing a picture of Bodhidharma, Wakuan asked, “Why does that son of a western barbarian have no beard?”

Bodhisattvas: Zen master Wakuan was born in 1108 and died in 1179, in the Sung Dynasty. In his time many foreigners entered China from India, Persia, and other countries of Central Asia. The Chinese called them all foreigners. The majority of Chinese people even called them barbarians, as they thought they themselves were the only civilized people, living at the very center of the world. Zen teachers used the slang of the day freely to express direct meaning. They called Bodhidharma “a son of a barbarian” or “that old blue-eyed barbarian.”

Today, too, Zen monks are so intimate with Bodhidharma that they do not call him master, lord, or teacher. Instead they call him “that fellow,” and many a time “this fellow.” Thus Bodhidharma is the monk, and the monk is Bodhidharma. To pay homage to Bodhidharma is to respect oneself, and one’s cup of tea is actually sipped by the lips of Bodhidharma. Probably Wakuan had shaved that morning, and, rubbing his chin with his hand, he might have said, “Well, well, the beard of Bodhidharma is all gone.”

In a picture, even in a photograph, we can see only the shadow, but not the real substance. If you add to the picture of Bodhidharma the missing beard, then you will miss his ears, or else his wrinkles. When you gather together all sorts of attributes, you can never encounter the real substance. No poem or prose can describe the fullness of Bodhidharma’s image. No music of worldly instruments can reproduce the voice of Bodhidharma’s preaching. Only in the palace of your inner self do you meet Bodhidharma face-to-face—nay, you open his eyes, and he smiles with your mouth and all your features.

Do not call it realization or enlightenment; such names will spoil your fun. You are a son of a barbarian. You ought to be satisfied with the name.

Mumon’s Comment

If you want to practice Zen, it must be true practice. When you attain realization, it must be true realization. You yourself must have the face of the great Bodhidharma to see him. Just one glimpse will be enough. But if you say you have met him, you have never seen him at all.

The last sentence is the most important for you. Did you ever experience meeting a person for the first time whom you did not feel was a stranger at all, or find yourself walking through a place that was somehow very familiar? Your friends may explain it to you using the theory of reincarnation or else they may pull you into the concoctions of astrology. As long as you hold your individuality tightly and cling to an ego-entity, you can please your friends by listening to their nonsense, but once you smell even a whiff of Zen, you cannot help but laugh at your friends’ ignorance.

Suppose you and I were business partners in a past incarnation, and I owed you some amount of money; you cannot collect even a cent from me, from this penniless monk. Suppose your stars indicate that you have a tendency to argue; if you make any noise and disturb others in the zendo, astrology or no astrology, I have to put you out. The stars are not forming your character now. Your own thoughts and actions are forming it. Even if you were a queen of Africa in your past incarnation, you cannot go back to being one now. So what is the use of worrying about meeting somebody from a former time or visiting some former place in person? In fact, no such animal to be called a person exists here. You feel familiar because you are one with that other person. You remember the place because you are in the place connected with all other places. You are on the verge of awakening to oneness; only your dualistic ideas prevent you. You and I have met each other many millions of years ago. Now, tell me where we have met!

If you pass this koan, you will also pass the fourth koan in The Gateless Gate, “A Beardless Foreigner.” Mumon said, “If you say you have met him, you have never seen him at all.” He really said a mouthful.

Mumon’s Verse

One should not discuss a dream

In front of a fool.

Why does Bodhidharma have no beard?

What an absurd question!

We are barbarians, and ought to be satisfied just to smile at each other.

1 From The Iron Flute, by Nyogen Senzaki and Tuth McCandless.

2 Japan had invaded China and was seeking possession of Manchuria during Senzaki’s work on The Gateless Gate.

3 Alponse and Gaston were names familiar to all in Senzaki’s era as personifications of well-bred gentlemenn whose polite behavior resulted in stalemates; each would insist that the other go first saying, “After you, Alfonse,” and “No, after you, Gaston,” ad finitum.

4 One of Senzaki’s favorite sayings of the Christian mystic Johannes Eckhard, known as “Meister Eckhart.”

5 Newsboys would call out “Extra, extra, read all about it!” as they tried to sell the latest edition of the newspaper.