Enlightenment, it turns out, can be found in a jar. Just ask Lancome, whose Hydra Zen “skin de-stressing moisturizer” sells for $42.50 in most boutiques. Or, if beauty products aren’t your bag, test drive a Ford Ranger pickup and “seek wisdom on a mountain top.” Along the way you can “thank heaven for 7-Eleven” and stop in for a bottle of Evian spring water, famous for its “eternal life force.” Or “seek the truth” in a glass of Heineken.

Oh, and once you get to the mountain top, don’t be surprised if you run into a group of scarlet-clad Tibetan monks running Lotus Notes on their IBM laptops, two companies that were recently “joined in spiritual harmony.” If you can’t find any monks on the mountain top, look for them on the basketball court. They’ll be the ones with the shaved heads and the Nikes.

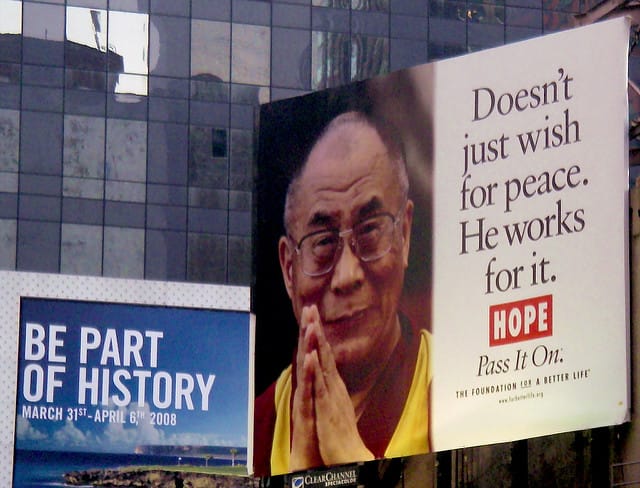

With so many real and fictional spiritual teachers pitching consumer goods these days—Apple nabbed Gandhi and the Dalai Lama for its “Think Different” campaign—you might want to cancel that trip to the mountain top and seek a guru in the local shopping mall instead. At least, that’s the message coming out of Madison Avenue these days.

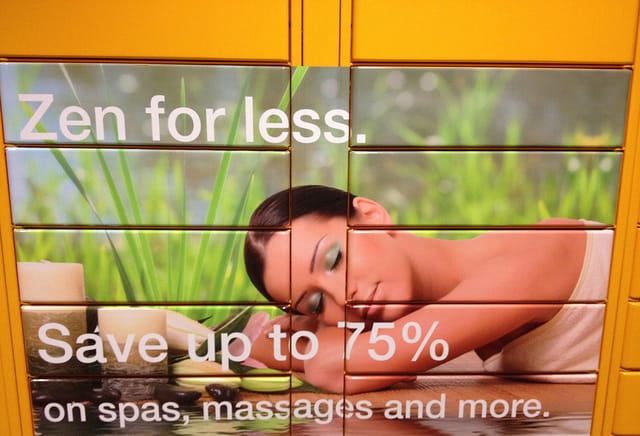

Advertisers are hawking everything from burgers to cars by appealing, ironically, to our most immaterial yearnings. “Serenity Now” is no longer just a funny Seinfeld line; it’s the unspoken philosophy behind a distinctly nineties’ breed of commercial—the spiritual ad. Fielding an army of angels, enlightened sages and barely disguised religious figures, advertisers are hoping to cash in on the quest for inner peace by teaching us, as Chapman University sociologist Bernard McGrane puts it, that “life becomes radiant through consumption.”

“If consumerism is the religion of our day, then advertising is the liturgy and the high priest,” says McGrane, a media critic and author of two books on advertising. “It has the same all-pervading quality as the church in the Middle Ages. It’s everywhere. It permeates everything from the bottom of your shoe to the back of your shirt to the car you’re driving.”

As it preaches the salvation that comes through buying and having, advertising also is subtly changing how we think about spirituality and ourselves. Just as it did with sex in the fifties and sixties, advertising is well on its way to taking our highest spiritual yearnings and transforming them into the profitably banal.

Appropriating spiritual images and language to sell stuff is nothing new, of course. In the old days of advertising, Xerox used monkish scribes to sell photocopy machines, and Hebrew National hot dogs claimed standards for meat exceeding the USDA’s because they had to “answer to a higher authority.” But today’s versions of these ads are far more common and they reflect a growing interest in things spiritual that spans the consumer spectrum from bestsellers (The Celestine Prophecy) and TV shows (“Touched by an Angel”) to teen jewelry inscribed with the initials “WWJD” (What would Jesus do?).

In this case, Jesus would probably throw his TV out the window. Few of the rest of us do. By the time the average American reaches 20 they will have seen about one million TV commercials. For those of us who grew up in the TV age, those numbers add up to an undeniable truth: we have been programmed since childhood to seek fulfillment through buying.

No less a figure than S.I. Newhouse, Jr., chairman of Conde Nast magazines, decries the rising influence of Madison Avenue. “Advertisers have taken over the world,” the publisher of Vogue and Vanity Fair complained to the New York Times in August. Few doubt the industry’s lengthening reach—ads are perhaps the primary socialization force on earth. The industry is all the more influential because they are designed not to appear influential. The less we pay critical, conscious attention to advertising, the more powerful its effects upon us. And it can transform anything into a part of the consumer universe, even the anti-materialist creeds of spirituality.

A case in point. Flip through any recent women’s magazine and you’ll come across an ad for a new hair shampoo called Abba. A model with angelic features stands facing the viewer, her blonde hair tossed by a breeze. Straightforward enough, right? But a reading of the accompanying text hints at more. We’re told that Abba can “harness the healing power of nature,” and help you “rediscover how real beauty comes from within.”

Hmm. Leaving aside the question of why you would buy a shampoo to get what can only be had from within (what ads and Zen koans have in common is that they always defy logic), let’s consider the “healing power” of Abba. On closer inspection it turns out the model is standing in a desert. Her hands are opened palm out in supplication at her sides. She is dressed in a shapeless, nearly monkish black dress. The sun lends her a halo.

If none of this rings a bell, consider that Abba is the word for “father” in Aramaic, the language of Jesus. It is also the root of the honorific “abbot,” a term first applied to the desert hermits of early Christianity. The “healing power” Abba is selling will do more than cure a few split ends. It’s not enlightenment, true, but what do you want for less than $10—God?

“Most marketing books tell you to go for some real estate in people’s heads,” says Doug Gilmour, president of Gilmour Associates, a Larkspur, California advertising firm that specializes in New Age-style campaigns for health food companies. “I want to go after some real estate in their souls.”

Whether they aim for our souls or our karma (Finlandia Vodka and Volkswagen both hype reincarnation in their current campaigns), advertisers say they are simply mirroring the public’s current fascination with spirituality.

“We are not devious people setting out to manipulate you into buying something,” says Myra Stark, senior vice president and director of knowledge management at Saatchi & Saatchi in New York, one of the nation’s largest advertising firms. “We’re people who try to understand what a brand or product means to a consumer, and the consumer either connects with that image or doesn’t connect.”

A consumer study initiated last year by Stark points to a less innocent conclusion. The study was designed to help Saatchi & Saatchi better understand consumer beliefs and attitudes about spirituality and their perceptions of brand names. After defining spirituality as “concern with things of the spirit, the values and the meaning of life, rather than everyday and material things,” Stark explains, the study found that when companies forge an intensely emotional bond with consumers through use of spiritual symbols, it spurs sales. Especially sales, she might have added, of those “everyday and material things.”

“The bottom line is, they’re all praying for good business,” complains Marc Balet, partner in Balet & Albert, a New York ad agency whose clients include Georgio Armani and Anne Klein. “It’s like seventies’ bellbottoms. They glom on to whatever’s hot now and in another three months they’ll have moved on to the Jetsons.”

It may be disingenuous of advertisers to claim they are only a mirror of society, when people pay $150 for the right brand name on their jeans and young women starve themselves to look like Kate Moss. But in hitching a ride on spirituality, the pitchpeople are definitely behind the curve, racing to keep up with the interests of their biggest meal ticket, the Baby Boomers.

As the largest group of children ever in America, the Boomers were targeted by Madison Avenue from the beginning. Not surprisingly, they grew up acutely aware of themselves as consumers. Today the youngest member of the former Pepsi Generation is 35, the oldest 53, and for maybe the first time in their lives they are staring death in the face. Or at least glancing in that general direction.

The result, predictably, is a sudden resurgence of interest in the spirit. While more and more of us are turning our backs on mainstream religion, our fascination with spirituality has gone through the roof. In the four years between 1993 and 1997, the number of Americans who said spirituality was important to their lives jumped from 58 percent to 75 percent—an astonishing statistical turnabout for such a short time span.

“The spiritual earthquake,” as Psychology Today founding editor T George Harris calls it, has sent shock waves through the religious spectrum, kicking up forms of spirituality undreamed of a generation ago. The current crop of spiritual schools reads like a self-improvement editor’s Dream Team: creation spirituality, Eucharistic spirituality, native American spirituality, Twelve-Step spirituality, feminist spirituality, earth-based (Gaia) spirituality, eco-feminist spirituality, Goddess spirituality and men’s spirituality, as well as the traditional Judeo-Christian brand and, of course, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, and all things Eastern.

Advertisers, who after all are members of the culture, can’t help but notice the new fad. And what they notice, they use.

“Basically, advertising is just a writer and an art director in a room, trying to come up with hundreds of ideas to pitch to the client and hoping that one sticks,” says John Lombardi, a former art director for McCann Erickson who dropped out of the business to work for the San Francisco Zen Center. “They have to produce, so they use whatever they see going on in the world around them, and they don’t make a moral distinction between using swing dancing or professional wrestling, or Zen.”

But then, morality was never a big hit with advertisers. Author Thomas Frank established in his The Conquest of Cool that advertising’s great achievement in the years since the 1960s has been to incorporate the idea of dissent from the doctrine of consumption into the doctrine itself. So we find Canon naming its new camera “The Rebel,” and Burger King telling us, “Sometimes you’ve gotta break the rules.” As novelist Jonathan Dee put it in a recent Harper’s essay: “The perfect capitalist-realist hero (is) a ‘rebel’ whose dissent is confined to the products he chooses to buy.”

And what works for the rebel works for the saint.

The Dalai Lama peers beneficently down from the billboard beside the freeway. His gentle visage radiates not only his own wisdom but the wisdom of the Buddhas throughout the ages. He is at once a Nobel Peace Prize winner; the leader of the international movement to free Tibet; the human embodiment of Avalokiteshvara, bodhisattva of Compassion, and a symbol of everything that is not greed, unbridled desire, and thoughtless materialism.

And he’s a spokesman for a computer company.

If you’re like most of us, you saw that billboard and your first thought was something like: “Oh, I love the Dalai Lama! Apple is so cool to use the Dalai Lama in its ads.” The subtext: Next time, maybe I’ll buy a Macintosh.

“What advertising has done is to co-opt our deepest yearnings and use them to sell us Rice-a-Roni, a house in the country, and the next fastest computer chip,” says Bob Whalley, an Episcopalian minister who teaches a class in spirituality and the media at the University of San Francisco. “They take our yearning toward humanity and transcendence and transform it into a yearning to buy.

“Whether this is comedy or tragedy depends on whether there are any absolutes or hopes in how we look at what it means to be human. If it’s okay for us to be just consumers, then that’s fine. But if we think part of being human is to foster deeper communion and community, and advertising precludes that, then it’s terribly sad.”

Advertisers, of course, would prefer we see their work as a cosmic comedy; humor is their weapon of choice. In a new print ad promoting the Ford Ranger SuperCab (“the planet’s coolest 4-door compact pickup”), the humor borders on ridicule of meditation. A young man (“Spence”) is seated with crossed legs, closed eyes, and an ironic smile in front of a pile of expensive toys—scuba gear, skis, a bicycle, an electric guitar. In the background, atop a hill, is the new truck, its interior lit by the same golden glow that outlines Spence.

The text reads: “Spence put a new twist on an old philosophy. To be one with everything, he says, you’ve gotta have one of everything. That’s why he also has the new Ford Ranger. So he can seek wisdom on a mountain top. Take off in hot pursuit of enlightenment. And connect with Mother Earth…. He says [the truck] gives him easy access to inner peace. Which makes him one happy soul.”

It’s easy to see why humor is one of the dominant tools of the trade. By laughing at Spence’s unrealized spiritual aspirations, the ad lets us impose an ironic distance between ourselves and our own decidedly un-enlightened behavior. The underlying message is: Forget meditation; the only thing that really counts is having the right toys.

The Ford ad illustrates how advertisers use the medium to trivialize spirituality. When the ultra-materialist Spence mimics a meditator, or when Victoria’s Secret parades a bevy of lingerie-clad supermodels and asks, “What kind of angel are you?” they aren’t celebrating the special qualities of meditation and angels. They’re using these spiritual images to promote ideas that lie precisely opposite the images’ original meanings. Thus desirelessness is correlated with materialism, and purity with sex.

Of course, sex was the target of the advertisers’ switch play long before they ever thought of trying it on spirituality. We have become so accustomed to bikini-clad babes popping up in commercials for automobiles and health clubs that we no longer even question the connection between product and promise. This objectification of women (and lately men) to sell products has transformed the “mysterium tremendum” of human sexuality into “tits and ass,” says Whalley.

Now he fears that we face the same danger with spiritual ads. “When the mystery of our spiritual side is turned into car ads,” Whalley says, “we lose our sense of the awesome. The world is actually both very small and very big; incredibly intimate and also awesome beyond belief. But when everything, even spirituality, is reduced to buyable terms, we end up with bite-sized chunks of possibilities that keep us from either fasting or feasting.”

Do advertisers see the irony in using an essentially anti-materialist message to sell us stuff? Well, yes and no.

“Sure they see the irony,” says Lombardi, “and they don’t care. It’s not a very nice business. It’s filled with a lot of soulless people. It’s kind of hard to embrace spirituality and be in advertising. Your client is Exxon and they just crashed the Valdez in Alaskan waters. Your job is to make that look good. Or your client is Ortho and your job is to sell herbicide to people in their back yards and you know it’s not good for them, not good for the planet.”

“The whole manipulation aspect of the business never sat right with me. Advertisers can get you to believe anything. They could spend their time trying to improve the world. It’s so powerful: they could really change some of the terrible things going on—drugs, guns, gangs. Instead, they’re trying to get you to believe spirituality can be had through buying things.”

Still, blaming advertising for all the ills of capitalism is a bit like shooting the messenger. One can almost—almost—feel sorry for the pitchpeople, always taking it on the nose for doing their jobs. And even if we can’t muster compassion, let’s admit that not everything about advertising is bad. Ads can be funny (Pepsi’s little girl imitating Marlon Brando). They can be touching (Kodak’s memorable moments). Occasionally, they can even help the spiritual quest.

Humans, after all, need a helping hand on the long hard road to self-actualization or enlightenment. As long as we know the food or the clothing we buy is simply a prop to help us along the path, we can use it in the spirit of Garrison Keilor’s powder milk biscuits, which “give you the strength to do what needs to be done.” This “journey talk” fosters a kind of manna-consciousness that helps us cross the spiritual desert without fear of starving.

Nor are all advertisers hungry ghosts intent on seducing us off the path. Doug Gilmour, for instance, is serious when he says he’s appealing to people’s souls. His “You are energy; energy is you” ad for Clifbar, the popular protein bar, grew out of his belief in “the mature male warrior ideal, and participating in the community in a humble way,” he says.

Yet even if it is not a vast conspiracy designed to trivialize or deny our spiritual motivations, the new spiritual advertising is certainly the product of a lot of unintentional small conspiracies. The cumulative effect of individual decisions by ad copywriters and artists vastly exceeds their expectations or design. Like news reporters whose reliance on government sources during wartime makes them little more than propaganda tools, advertisers have unthinkingly absorbed the nonmaterialist themes of spirituality and twisted them into a kind of Big Brother doublespeak.

Maybe the clearest portrait of the consequences of this new anti-theology appeared in the film Network, when the television executive played by Ned Beatty holds forth on his peculiarly Orwellian vision of the future. Raising his hands skyward and beaming with satisfaction, Beatty envisions a vast web of global corporations whose products instantly gratify consumers’ every desire, assuring that “all anxieties are allayed.”

Meditation? Wouldn’t you rather have a Pepsi?