Though he lived as a simple householder yogi, Thinley Norbu Rinpoche’s impact was far-reaching, says his longtime student Samuel Bercholz.

On a sunny day in the Paro Valley of Bhutan, the air was crisp and clean, flags of the five colors were snapping in the wind, and hundreds of yogis and yoginis were chanting and playing their chod drums, bells, and thigh-bone trumpets—the Dudjom Tersar Throma practice—as an offering to the kudung (the deceased physical form) of Thinley Norbu Rinpoche. His cremation was a fortnight away.

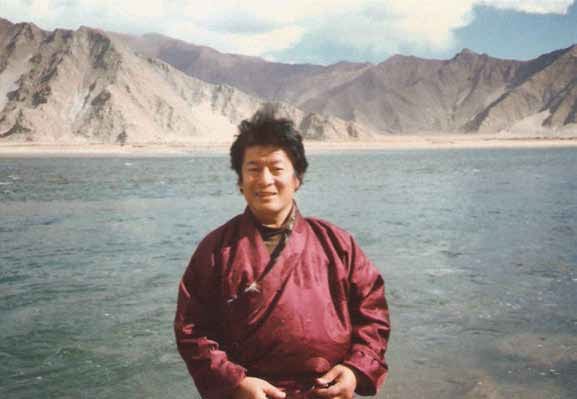

Who was this man who brought together kings and queens, ministers and officials, thousands upon thousands of Bhutanese, Tibetan, Nepali, Chinese, European, and American disciples to honor his life and to receive the blessings of his passing into dharmakaya? In the world of Tibetan Buddhism he was renowned as the living essence of Omniscient Longchenpa, the great Nyingma scholar–yogi of the fourteenth century who had been especially important in the transmission and development of the Dzogchen teachings.

He was the first son of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche, former head of the Nyingma lineage, and was believed to be an emanation of Tulku Drime Oser, a son of the great terton Dudjom Lingpa. He spent the last three decades of his life in the United States, living in New York City and then rural New York State and in the desert in California. He dressed simply, often just in a shirt with a bath towel wrapped as a sarong. He and his environment were impeccably clean. He had no dharma centers; the students who gathered around him practiced in his home and in the homes of fellow practitioners. He made little fuss about anything, and practiced every evening with his students, whether it was just a handful or a score. One of his main teachings was about the continuity of practice—meditation, offerings, and becoming familiar with Buddha and deity phenomena. His approach was simple, direct, and profound. He taught that development of the proper view and faith was paramount—faith meaning that once one had heard and considered the teachings, one actually put them into practice.

Every one of his students, including myself and my immediate family, were continuously blessed by his profound instructions, in the same way that practitioners in the past must have been blessed by the likes of Saraha, Padmasambhava, and Longchenpa. His American community was an interesting mixture of males and females of all ages and almost equally made up of Tibetan, Bhutanese, Chinese, and Westerners—all practicing as one harmonious group. He put particular emphasis on teaching and training his youngest disciples; some trained from birth and others trained continuously from a very young age into their twenties. He held nothing back. They were trained in meditation, sadhana, dharma dance, scholarship, and discipline. This young group of disciples will be an important legacy to the world. His son, Garab Dorje Rinpoche, will continue their training. Though living the quiet life of a householder yogi, Buddhist teachers from all over the world came to meet him and receive teachings. He was a teacher of teachers.

Thinley Norbu was also a brilliant writer. He often apologized for his “bad English” despite using the most accurate vocabulary and nuances of the English language. His magnum opus, The Cascading Waterfall of Nectar, contains the pith teachings of the complete Buddhist path up to and including Dzogchen. It will be studied and appreciated by those fortunate enough to be challenged by it for centuries to come.

I count myself as one of his fortunate disciples, having had the great good fortune to spend more than twenty years with him, to be X-rayed by him, to be fried by him, to be simmered by him, to appreciate his great loving care and endless compassion. He is no different than the Buddha in person.

For a selection of teachings from the works of Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, see The Wisdom Mind of Thinley Norbu: A Selection of Teachings.