Question: I don’t identify exclusively with any one Buddhist tradition but rather find it helpful to learn from various ones, such as Zen, Vajrayana, Theravada, and Pure Land. Sometimes I’m criticized for not focusing solely on one tradition, but I don’t see what the problem is. Why shouldn’t we make the most of this incredible opportunity to learn from the many Buddhist traditions that have come to the West? After all, I even see Buddhist teachers studying with teachers outside of their tradition.

Narayan Helen Liebenson: You hear this kind of criticism because of a well-founded concern that one’s practice may become superficial and thus bring superficial results. Moving from tradition to tradition without being at home in any one of them is said to be like digging many small holes instead of one deep hole.

On the other hand, in the West, and especially in the U.S., there is a wonderful and remarkable coming together of a rich array of Buddhist traditions. In the past, most Asian countries had one tradition and sometimes only offered one way of practice. If it wasn’t the right one for you, you were pretty much out of luck. Here, almost anyone can find a practice that suits them.

It is true that a number of Buddhist teachers study with teachers outside of their tradition. For me, although I am most at home in the Insight Meditation tradition, I am also deeply connected to the Chan tradition and practiced with Master Sheng Yen for ten years. I remain connected to this lineage in unexpected ways.

One piece of advice I received on this same question came while I was practicing with Ajahn Maha Boowa in a Thai Forest monastery many years ago. The advice was to remain with one teacher for five years and give it your all. After this initial training period, it’s okay to move on if you want because you will have a firm foundation upon which to rest. This advice was for monks and had to do with teachers and monasteries, not lineages and traditions, but I see it as applying to your question as well. If someone is dedicated to the path of liberation, five years seems like the minimum time commitment needed to thoroughly learn one tradition.

Some people will remain in one tradition for their entire practice lives, and that will be enough. Others, like you, will be open to the many traditions within Buddhism. For me, it’s not that there was or is anything lacking in the Theravada tradition; I simply met a teacher in the Chan lineage with whom I had a strong affinity.

I don’t see your openness as necessarily problematic so long as you have wise view and know precisely how to practice. But if you find yourself succumbing to confusion, you need to choose one tradition and stick with it.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: I agree with you that there is much to learn from each of the Buddhist traditions that are now available to us in the West. In the early years, San Francisco Zen Center hosted many Buddhist teachers from different traditions, and I appreciated the opportunity to hear them teach. Over the years, I have done retreats with teachers trained in the various schools of Zen, Vajrayana, and Insight Meditation, and I have been inspired by many teachers who are living their lives guided by the teachings of the Buddha.

However, once you make a strong connection with a teacher who inspires you, you should consider moving from search mode to engagement. When I first met Suzuki Roshi, I thought, “I want to be like him! ” The best teacher for you is someone who inspires you by the wisdom and compassion you see in them as they go about their daily life and interact with the people around them.

I wouldn’t recommend engaging with multiple teachers at once. It’s best to give your full attention and effort to one teacher and sangha. If the sangha has multiple teachers available, you may need to speak one-on-one with several teachers to discern who is the best fit for you as a primary teacher.

Kobun Chino Roshi once said, “When you realize how rare and how precious your life is, and how completely you are responsible for how you live it, how you manifest it, it’s such a big responsibility that naturally such a person sits down for a while.” Are you willing to sit down for a while and commit to a teacher, sangha, and practice?

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: In order to mature on the spiritual path, it is important to have a teacher with whom you make a heart connection. When you receive instruction from that teacher, you need to take those instructions into your life and practice them until you have experiences and realization. This process requires trust, love, and commitment.

There are individuals with enough realization, and more important, stability, who can be exposed to many ideas and process them without weakening their commitment and the stability of their practice. If someone is open, capable, and stable, then it is fine to learn from different teachers and traditions— and areas outside of Buddhism, such as science, anthropology, and philosophy. But while there is no limit to what we can learn from others, it is important to narrow down the number of practices you engage in, because practice requires long and deep commitment in order to bear fruit.

It is important to explore what’s motivating you to leam from many traditions and teachers. Listen deeply to discern if you are in search mode, driven by an underlying feeling of dissatisfaction. Without realizing it, we can spend years in this mode, wandering and collecting knowledge, all the while not connecting with our underlying hunger. If this is the case, we are not really trying to find a teacher or to become more intimate with our actual experience. This is a form of spiritual materialism, and it is an obstacle to spiritual realization. If you look more deeply and honestly you may realize that you are lost, and this realization can be a genuine beginning to your path.

If this is the case, it is important first and foremost to find a teacher you respect and will come to love, and a path and practice you can commit to, then dedicate enough time with that teacher and the teachings and practices to develop confidence and maturity. During this time you can be open to others, not replacing or rejecting your master or your practice, but complementing, enriching, and expanding your life. However, if in listening to others you become confused, stop and concentrate on your path.

Confusion is the sign you must not ignore. First, we acknowledge our confusion in order to recognize the need for a teacher and a path, and later our pain continues to guide us to deepen our commitment and realization. Pain or insecurity is always the sign to stop and deepen your connection with yourself rather than to search outside yourself to fill what is missing.

As humans, we can love every human being, be inspired by many people, and have deep friendships with some. But we can’t build deep intimate relationships with everybody. If your main relationship is not deep enough, then having relationships with many people can create instability. For example, a husband or wife has spiritual and emotional and physical intimacy with their partner, and that person can also have emotional intimate relations with a small group or family. They can have true dharma brothers and sisters and a sense of emotional commitment, a feeling that they would do anything to help them and be present for them. But if you expand more than you are capable of, it causes confusion and you don’t reach your full capacity as a human. In the process of expanding, you may disconnect from those with whom you do have intimacy.

My advice is to listen with your heart and also analyze with your intellect to see if there is value in the criticism that you are not focusing solely on one path. Do you have a path, a practice, and a teacher you truly follow? If not, the first priority is to find that. Once you find that connection, you will be able to deepen spiritual intimacy through practice and commitment. Then, when you listen to other teachers who might have different views, it is not masking your confusion or adding to it; instead, it is enriching your life. But you must reflect and know your own capacity. Others cannot truly discern this for you. Only you can follow your heart and know whether you are in true relationship with your path. 0

Email your questions to [email protected]

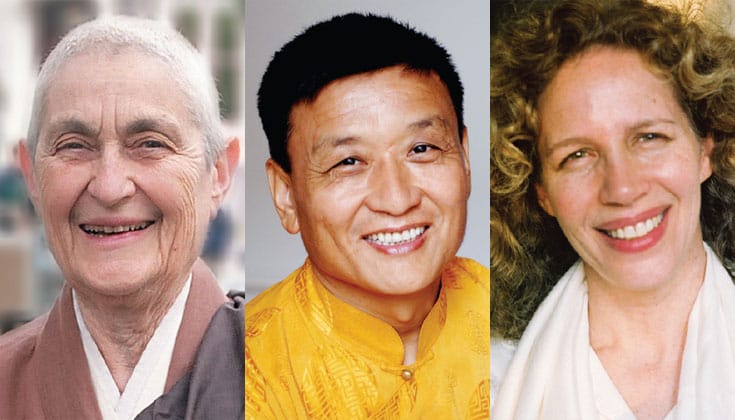

Zenkei Blanche Hartman is former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is a lineage holder of the Bön Dzogchen tradition of Tibet.

Narayan Helen Liebenson is a guiding teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Center.